The Commonwealth's Layers Revealed

Massachusetts

Massachusetts occupies a unique place in the American consciousness: simultaneously the cradle of liberty and a progressive powerhouse, a state where Puritan ghosts mingle with biotech innovators in the morning mist. Yet beyond the Freedom Trail’s well-worn cobblestones and Cape Cod’s summer crowds lies a more complex Commonwealth, one where mill towns reinvent themselves as art centers, where cranberry bogs stretch like ruby carpets, and where locals still debate the proper pronunciation of “Worcester” (it’s “Woo-stah,” for the record).

This is a state that manages to pack an entire nation’s worth of history, culture, and contradictions into just 10,554 square miles. It’s where America arguably began, yet it consistently looks toward the future. It’s deeply traditional yet radically innovative. And while tourists flock to its famous sites, the real Massachusetts reveals itself in quieter moments. In the echo of textile looms transformed into artist lofts, in the salt spray over Gloucester’s working harbor, and in the hushed reverence of Concord’s author’s ridge.

Table of Contents

- Geography & Natural Landscape

- Historical Timeline & Key Events

- Cultural Identity & Regional Character

- Economy & Industry Evolution

- Politics & Governance

- Cities, Towns & Population Centers

- Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

- Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

- Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

- Share your Massachusetts route 1 memory

- Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

- Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

Geography & Natural Landscape

The Lay of the Land

Massachusetts, despite being the 7th smallest state, has four unique climatic zones across an area of 10,555 square miles. From east to west, they are the Coastal Plain, the New England uplands, the Pioneer Valley, and the Berkshire and Taconic Mountains.

This geographic diversity creates a surprisingly varied landscape that has profoundly shaped the state’s development and character.

The eastern third of the state hugs the Atlantic, creating the jagged coastline that gave Massachusetts its maritime soul. Here, rocky headlands alternate with sandy beaches, while protected harbors like Boston, Gloucester, and New Bedford provided the foundations for centuries of seafaring commerce. The coast’s most distinctive feature is Cape Cod, that flexed arm of sand reaching 65 miles into the Atlantic. It’s a large glacial moraine that was created when the glaciers retreated.

Moving inland, the landscape rises gradually through rolling hills dotted with the remnants of colonial farms, their stone walls still marking boundaries through second-growth forests. The Connecticut River Valley, known locally as the Pioneer Valley, cuts a fertile swath through the state’s interior. In this valley, the terrain is much flatter and covered in rich alluvial soils.

Mountains and Valleys

The western edge of Massachusetts presents a dramatically different face. At 3,491 feet, Mount Greylock is the highest point in Massachusetts. From its peak on a clear day, you can see as far as 90 miles away. Sight lines of up to 72 miles (116 km) are possible from Greylock.

This mountain, part of the Taconic Range, represents a geological story distinct from the nearby Berkshires. Mount Greylock is part of the much larger Taconic Allochthon, a structure that migrated to its present position from 25 miles to the east. The rocks moved via thrust faulting, a tectonic process by which older rock is thrust over and above younger rock.

Mount Greylock summit with the Veterans War Memorial Tower

The Berkshire Hills dominate the western portion of the state, creating a landscape of steep valleys, swift streams, and dense forests that feels worlds away from the coastal lowlands. The Taconic hills and the valleys that separate them are marked by an underlying geology that is vastly different from other areas of the state. There are marble valleys, limestone outcrops, and calcareous glacial deposits found here, creating rich soils that support plant communities not found elsewhere in Massachusetts.

Climate Zones and Natural Patterns

Massachusetts’ climate reflects its geographic diversity. Humid Subtropical (Cfa): This climate zone has warm-to-hot summers with cold-to-mild winters. Humid Continental (Dfa): This climate zone has warm-to-hot (humid) summers with cold (sometimes bitterly cold) winters.

The state’s position at the intersection of continental and maritime influences creates notably variable weather. Locals joke that if you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes.

Zones in Massachusetts range from 5a in the Berkshire mountains to 7a on Cape Cod. Most of western Massachusetts is in zone 5b, while most areas in coastal eastern Mass are now designated as zone 6b, where the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature is between 0 and -5 degrees F.

This variation in climate zones has profound implications for everything from agriculture to architecture.

The Hand of Ice

Perhaps no force has shaped Massachusetts’ landscape more dramatically than glaciation. Between 14,000 and 22,000 years ago, during the Wisconsin Glacial Episode, the entire state of Massachusetts was covered in ice. This glacial period radically altered the state’s topography, making large swaths of New England soil rocky, acidic, and infertile. The glaciers rounded off mountains, changed the course of rivers and streams, leaving behind thousands of small lakes and ponds. Even today, a vast majority of the state’s landscape is covered in glacial features and deposits.

The retreating ice sheet deposited glacial till that forms the basis for our soils, well-known for being quite rocky. Glacial movement shaped the region’s landforms and water bodies. Distinctive features, including Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, were formed by the glacier’s terminal moraine and outwash plains.

Historical Timeline & Key Events

Before the Mayflower

Long before European sails appeared on the horizon, Massachusetts was home to numerous indigenous peoples. Massachusetts was originally inhabited by tribes of the Algonquian language family such as the Wampanoag, Narragansetts, Nipmucs, Pocomtucs, Mahicans, and Massachusetts.

These nations had developed sophisticated societies, with established trade routes, agricultural practices, and governance systems that would later influence colonial development.

The Pilgrim Landing and Plymouth Colony

The story that every American schoolchild knows began on a cold December day in 1620. On December 18, 1620, with the English ship Mayflower anchored in Plymouth Harbor, Massachusetts, a small party of sailors from the vessel go ashore, as its passengers prepare to begin their new settlement, Plymouth Colony. Yet this familiar narrative obscures the complexity of what actually transpired.

Upon arriving in America, the Pilgrims began working to repay their debts. Using the financing secured from the Merchant Adventurers, the Colonists bought provisions and obtained passage on the Mayflower and the Speedwell. They had intended to leave early in 1620, but they were delayed several months due to difficulties in dealing with the Merchant Adventurers, including several changes in plans for the voyage and financing.

The Mayflower Compact, signed aboard ship, represented something revolutionary: Written and signed on November 11, 1620, the Mayflower Compact was a social contract the pilgrims created in order to establish law and order in Plymouth Colony. Since the colonists only had permission from the king to settle in Virginia, they drew up the contract to establish English law in the new colony in New England until they could obtain a new patent from the king. In the compact, the pilgrims declare themselves loyal subjects of King James and vow to work together to abide by and uphold English law in the colony.

The First Winter and Survival

The romantic narrative of the First Thanksgiving obscures a grimmer reality. That winter of 1620-1621 was brutal, as the Pilgrims struggled to build their settlement, find food and ward off sickness. By spring, 50 of the original 102 Mayflower passengers were dead. The colony’s survival depended entirely on indigenous knowledge and assistance.

Soon after they moved ashore, the Pilgrims were introduced to a Native American man named Tisquantum, or Squanto, who would become a member of the colony. A member of the Pawtuxet tribe (from present-day Massachusetts and Rhode Island), Squanto was kidnapped by the explorer Thomas Hunt and taken to England, only to escape back to his native land.

With peace secured thanks to Squanto, the colonists in Plymouth were able to concentrate on building a viable settlement for themselves rather than spend their time and resources guarding themselves against attack. Squanto taught them how to plant corn, which became an important crop, as well as where to fish and hunt beaver.

Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Great Migration

Plymouth, despite its fame, was soon overshadowed by its larger neighbor. It is estimated that more than 20,000 settlers had arrived in Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1630 and 1640 (a period known as the Great Migration), and the population of all New England was estimated to be about 60,000 by 1678.

This massive influx transformed the region from a precarious foothold to a thriving colonial society.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, centered in Boston, quickly became the economic and cultural heart of New England. Unlike Plymouth’s separatists, these Puritans sought to create a “city upon a hill”, a model Christian society that would serve as an example to the world. This vision would profoundly shape American ideals of exceptionalism and moral purpose.

Revolution’s Cradle

By the 1760s, Massachusetts had evolved from a religious refuge to a hotbed of political radicalism. This increased friction between the colonists and the Crown, which reached its height in the days leading up to the American Revolution in the 1760s and 1770s over the question of who could levy taxes. The American Revolutionary War began in Massachusetts in 1775 when London tried to shut down American self-government.

The familiar scenes played out across the Commonwealth: the Boston Massacre, the Tea Party, Paul Revere’s ride, the shots fired at Lexington and Concord. Massachusetts provided not just the stage but many of the principal actors in America’s founding drama. The commonwealth formally adopted the state constitution in 1780, electing John Hancock as its first governor.

The Industrial Revolution

If Massachusetts gave birth to American independence, it also midwifed the nation’s industrial transformation. The industrial revolution was brought to America by a British-born merchant, Samuel Slater, who built the first successful cotton spinning mill in America in Rhode Island, and also by an American merchant, Francis Cabot Lowell, who built the first integrated cotton spinning and weaving facility in America in Massachusetts. Lowell, who was born in Newburyport, Mass, in 1775, was a successful merchant who visited England in 1810, at the age of 36, and was so impressed by the British textile mills that it inspired him to start his own mills. In 1813, Lowell and several partners formed the Boston Manufacturing Company and introduced a power loom, based on the British model, that had been tweaked with many technological improvements.

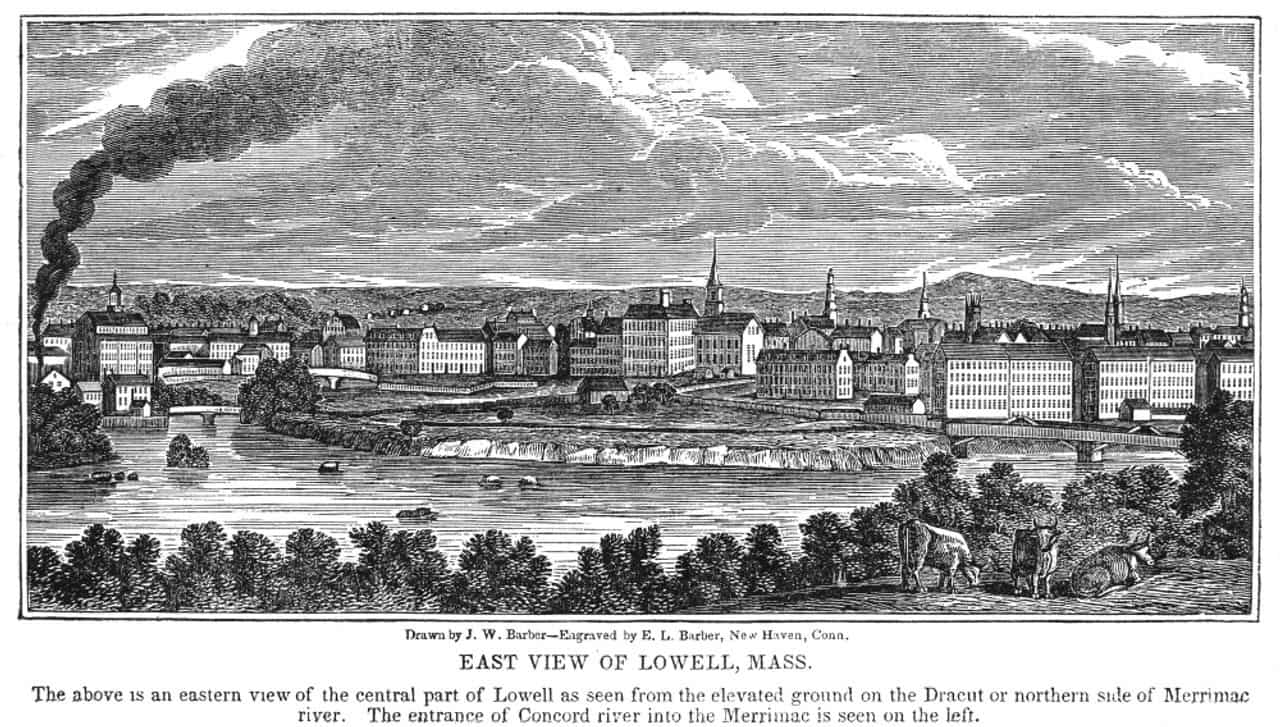

The transformation was swift and profound. Francis Cabot Lowell was largely responsible, however, for raising the state to its manufacturing eminence. Lowell went to England to study methods of textile operations and, after his return, built a power loom in Waltham in 1814. He died in 1817, but his associates developed Lowell, the country’s first planned industrial town, with its mills driven by the Merrimack River.

Immigration and Social Change

The mills’ hunger for labor transformed Massachusetts’ demographics. Yankee ingenuity fostered much early handicraft-based industry, though the influx of unskilled, low-paid labourers from Europe during the 19th century was the necessary ingredient for the mass production that developed in the state’s shoe and textile factories. Waves of Irish, Italian, Portuguese, and French-Canadian immigrants created the ethnic mosaic that still characterizes many Massachusetts cities.

This period also saw Massachusetts at the forefront of social reform movements. In the early 19th century, Boston was a center of the socially progressive movements in antebellum New England. The abolitionist, women’s rights, and temperance movements all originated in New England, and Boston became a stronghold of such movements. Boston also flourished culturally with the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne becoming popular. The belief in social progress was strongly influenced by the Second Great Awakening sweeping the Northern United States at the time, and Boston gained a reputation for radical politics.

Cultural Identity & Regional Character

The Massachusetts Paradox

To understand Massachusetts is to embrace contradiction. This is a state that prizes both tradition and innovation, that reverences its past while racing toward the future. The stereotypical Massachusetts resident (educated, liberal, slightly superior) exists, but so does the working-class Townie, the Portuguese fisherman in New Bedford, the Cambodian factory worker in Lowell, and the Yankee farmer in the Berkshires who votes Republican and has for generations.

The state’s character reflects layers of cultural sediment. The Puritan foundation never entirely disappeared; it morphed into a peculiar blend of moral certitude and intellectual rigor that manifests in everything from the state’s excellent schools to its sometimes sanctimonious politics. The Irish immigration of the 19th century added a layer of gregarious combativeness and machine politics. Later waves brought Italian exuberance, Portuguese industriousness, and more recently, Brazilian energy and Asian entrepreneurialism.

Regional Variations

Massachusetts contains multitudes, and nowhere is this more evident than in its distinct regions. Greater Boston dominates demographically and economically, but it’s hardly monolithic. Cambridge’s academic hauteur contrasts with Somerville’s hipster grit. The North Shore’s old money faces off against the South Shore’s Irish-American enclaves.

Western Massachusetts might as well be a different state. The Berkshires attract New York weekenders and maintain a genteel, cultural atmosphere centered on Tanglewood and summer theaters. But venture into the old mill towns of the Pioneer Valley, and you’ll find a grittier reality. Places like Holyoke and Chicopee that lost their industrial purpose and are still searching for new identities.

The Cape and Islands maintain their own distinct culture, shaped by isolation, the sea, and seasonal tourism. Year-round residents have a particular resilience, enduring winter’s isolation for summer’s bounty. The islands (Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket) have evolved from whaling ports to playgrounds for the wealthy, but scratch the surface and you’ll find old families who remember when you could buy a house for what a weekend now costs at a bed-and-breakfast.

The Massachusetts Voice

The Boston accent gets all the attention (pahking the cah in Hahvahd Yahd) but Massachusetts speech patterns reveal subtle class and geographic distinctions. The traditional Boston Brahmin accent, now nearly extinct, was entirely different from the working-class dialect that Hollywood loves. Western Massachusetts has its own patterns, influenced by proximity to New York and Vermont.

Language here serves as social marker. The vocabulary itself divides people: Is it a “rotary” or a “roundabout”? A “bubbler” or a “water fountain”? Do you drink “tonic” or “soda”? The answers reveal not just geography but generation and class.

Attitude and Outlook

If there’s a unifying Massachusetts attitude, it might be described as confident provinicalism. Many residents genuinely believe they live in the best place in America: best hospitals, best universities, best history, best seafood. This certainty can manifest as insufferable smugness to outsiders, but it also drives excellence. Massachusetts doesn’t just want good schools; it wants the best schools. It doesn’t just preserve history; it fetishizes it.

Harvard Yard in Fall bloom.

Yet beneath the confidence runs an undercurrent of anxiety. The state that launched America’s industrial revolution watched that same industry abandon it for the South and overseas. The mills that built fortunes became empty shells. The fishing industry that fed the nation struggles against depleted stocks and foreign competition. Even the vaunted knowledge economy concentrates wealth in ways that make the state increasingly unaffordable for the middle class.

Economy & Industry Evolution

From Cod to Microchips

The economy of Massachusetts today is based largely on technological research and development and the service sector (including tourism). This represents a major shift from the state’s preindustrial agricultural basis and maritime trade in the 17th and 18th centuries and the heavy manufacturing that characterized the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. This represents a major shift from the state’s preindustrial agricultural basis and maritime trade in the 17th and 18th centuries and the heavy manufacturing that characterized the 19th century and the first half of the 20th.

The economic history of Massachusetts reads like a series of reinventions. Foreign trade, fishing, and agriculture long buoyed the economy. Foreign trade, fishing, and agriculture long buoyed the economy. Salem sailors brought exotic goods from China, the West Indies, and other faraway lands. Fishing was lucrative, adventurous, and dangerous; more than 10,000 fishermen from Gloucester alone have lost their lives over the centuries.

The Textile Empire

Textile manufacturing became the dominant industry in Massachusetts during the Industrial Revolution and helped promote further industrialization of the state. The impact was transformative. Lowell, Massachusetts is known as “the cradle of the American Industrial Revolution” since it was the first large scale factory town in the country.

The company was so successful that it continued to expand into other New England towns such as Chicopee, Mass, Lawrence, Mass and Manchester, NH. By the 1850s, the Boston Manufacturing Company, which was by then renamed the Boston Associates, was responsible for a fifth of America’s cotton production.

The Lowell System revolutionized not just manufacturing but labor relations. Women have been a major part of the manufacturing industry for over two centuries, and that started with the Lowell Mill Girls. In the early days of his business, Lowell was having a hard time finding able-bodied workers as many Americans were hesitant to work in factories. So instead, he persuaded young, single women between the ages of 15 and 35 to come work for him. He built boarding houses for the women with chaperones and even provided educational opportunities to help his workers move on to better jobs like teaching and nursing. The work was hard and the women were paid half of what men would be, but it was still unheard of financial independence for a young woman of the time.

Boom and Bust

The textile industry’s trajectory illustrates a recurring Massachusetts pattern. In 1875, Fall River was undeniably the leading textile center in the United States. By 1925, the peak was reached and a collapse followed soon afterwards.

The Great Depression came early to the mills in Massachusetts and never left. By 1936, total textile employment had dropped to 8,000. Many mills were demolished or reduced in size to save on taxes.

The Modern Transformation

After manufacturing (particularly the textile and shoe factories) fell on hard times, high-technology industries and the service sector developed after 1950. By the early 21st century, Massachusetts’s economy was prospering because of the close relationship between the computer and the communications industries, as well as the many educational institutions of the metropolitan Boston area. Several factors ensured a profitable and productive economic system: less reliance on defense contracts; continued success in exports of high-technology equipment, minicomputers, and semiconductors; ongoing investments by venture capitalists; and the availability of a highly educated workforce.

The transformation from mill town to tech hub wasn’t smooth or universal. Route 128, the highway circling Boston, became “America’s Technology Highway” in the 1950s and 60s, hosting companies like Digital Equipment Corporation and Raytheon. But the minicomputer industry’s collapse in the 1980s proved Massachusetts hadn’t escaped boom-bust cycles: it had just found new ones.

Today’s Economy

Modern Massachusetts runs on education, healthcare, and financial services. The state hosts world-renowned institutions: Harvard, MIT, Massachusetts General Hospital, Fidelity Investments. Telecommunications and biotechnology also grew in importance. The growth of other services (finance law, education, insurance, and health care) also contributed substantially to the state’s financial well-being, especially because these activities were relatively well insulated from the caprice of consumer demand.

Yet prosperity brings its own challenges. The knowledge economy rewards the highly educated while leaving others behind. Housing costs in Greater Boston rival San Francisco and New York. Young families flee to New Hampshire or North Carolina, seeking affordability. The state’s population ages, straining the healthcare system it takes such pride in.

Maritime Heritage Endures

Despite economic transformation, the sea remains central to Massachusetts’ identity and economy. Fishing later suffered substantial reverses as well. A booming business up to the early 1960s, fishing began to wane late in the decade because of foreign competition in the traditional Atlantic fishing grounds and the depletion from overfishing of such species as haddock and lobster. By the late 1970s, however, the industry had made a comeback; Massachusetts now usually ranks as one of the top U.S. states in value of fish landings.

Politics & Governance

The Bluest State?

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is often categorized politically as progressive and liberal. All of the state’s U.S. representatives and senators are Democrats. Democrats also form the large majority of the state’s legislature, though the state has a history of electing Republican governors.

Yet this surface uniformity masks complexity. On a practical level, there is little benefit to registering under a party banner in Massachusetts, given the state’s semi-open primary system, where unaffiliated voters can participate in either party’s nominating contests. Just before the presidential primary earlier this month, Secretary of State Bill Galvin announced that 64 percent of Massachusetts voters are not registered under a party label (the state uses the sometimes confusing term “unenrolled” for such independent voters). This figure is up from 56 percent in 2020 and 53 percent in 2016. Just 27 percent of voters in this reliably blue state are now registered Democrats, while only 8 percent are registered Republicans.

A History of Contradictions

Massachusetts political history defies simple categorization. In presidential elections, Massachusetts supported Republicans from 1856 through 1924, barring 1912, where due to vote splitting between former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt running as a Progressive against incumbent Republican President William Howard Taft, Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson ended up becoming the first Democratic presidential candidate to win Massachusetts, though only winning with a plurality of only 35.53% of the vote. From 1928 up until the 1960s, it was considered a Democratic-leaning swing state. During the 1972 presidential election, Massachusetts was the only state to give its electoral votes to George McGovern, the Democratic nominee (the District of Columbia also voted for McGovern).

The state’s Republican governors often govern more like Democrats elsewhere. Despite the state’s strong Democratic lean, Republicans have been able to win the governor’s office. They held it almost continuously from 1991 to 2023 with the only exception being Democrat Deval Patrick (2007–2015). Although, they have mostly been among the most moderate Republican politicians in the nation, especially William Weld. Massachusetts’ most recent Republican governor was centrist Republican Charlie Baker, who was re-elected to his second term in 2018 with 66.6% of the vote.

Modern Voting Patterns

In recent presidential elections, Massachusetts has been reliably Democratic. Since 1900, Massachusetts has voted Democratic 68.8% of the time and Republican 31.3% of the time. Since 2000, Massachusetts has voted Democratic 100% of the time and Republican 0% of the time.

In 2020, Biden won Massachusetts with 66% of the vote to Trump’s 32%. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won Massachusetts with 61% to Trump’s 33%. Massachusetts has voted Democratic for the past nine presidential election cycles. The last Republican to win the state was Ronald Reagan, in both 1980 and 1984.

Political Culture

Massachusetts politics reflects a peculiar blend of high-minded idealism and bare-knuckled pragmatism. The state that produced the Kennedys also perfected machine politics. Town meetings, that purest form of direct democracy, coexist with backroom deals and patronage.

The state’s political culture values education and expertise, sometimes to a fault. Policy debates can resemble academic seminars, heavy on data and light on emotion. This technocratic tendency produces thorough, well-designed programs. Massachusetts’ healthcare reform became the model for Obamacare but can also seem bloodless and disconnected from regular people’s concerns.

Generational Change

Among the youngest registrants, those aged 18 to 20, an astonishing 92 percent registered as an unenrolled voter between 2020 and early 2023, the newest voter data file accessible for this analysis. This is an absolute explosion compared to seven years ago, when roughly two-thirds of the youngest voters registered were unenrolled.

This shift suggests Massachusetts politics may be entering uncharted territory. Without strong party identification, younger voters may be more volatile, more issue-focused, less predictable. The state that seemed politically settled may surprise yet.

Cities, Towns & Population Centers

Boston: The Hub

Boston doesn’t just dominate Massachusetts; in many ways, it IS Massachusetts in the national imagination. The city proper holds about 675,000 people, but Greater Boston encompasses 4.5 million. Nearly two-thirds of the state’s population. Bostonians call their city “The Hub,” short for Oliver Wendell Holmes’ phrase “The Hub of the Universe,” and while the nickname invites mockery, it captures something essential about the city’s self-perception.

Modern Boston is really a collection of former towns stitched together by annexation and infill. Each neighborhood maintains distinct character: Beacon Hill’s Federal-era elegance, the North End’s Italian heritage, Southie’s Irish-American pride, Jamaica Plain’s progressive activism. The old borders matter. A Charlestown native might live their entire life rarely crossing into Cambridge, though it’s just across the river.

The Gateway Cities

Beyond Boston’s gravitational pull lie the Gateway Cities (former industrial centers searching for new purpose. Lawrence, Lowell, Fall River, New Bedford, Springfield, Worcester) these places built America’s industrial might and bear the scars of its departure.

Worcester, the state’s second-largest city, exemplifies the challenge and opportunity. Once known as the “City of the Three Deckers” for its distinctive housing, Worcester has transformed its downtown, attracted biotech companies, and leveraged its central location. Yet poverty persists in neighborhoods that once housed mill workers, and the city struggles with the perception that it’s merely a waystation between Boston and Springfield.

Fall River tells a more melancholy tale. The number of spindles in Fall River mills doubled between 1855 and 1865 and quadrupled by 1875. Union Mills Company, founded in 1859, thrived during this period. Less variable temperature and slightly higher relative humidity along the southern coast provided better running conditions for fine cotton yarn production. In 1875, Fall River was undeniably the leading textile center in the United States. By 1925, the peak was reached and a collapse followed soon afterwards.

College Towns

Massachusetts’ college towns form their own category, places where academic rhythms override normal urban patterns. Amherst, Northampton, and Williamstown in the west; Cambridge and Somerville in the east, these communities blend youthful energy with intellectual intensity.

Cambridge deserves special mention. Home to Harvard and MIT, it functions as Boston’s brain, generating ideas and innovations that ripple globally. The city’s kendall Square has become one of the world’s premier biotech clusters. Yet Cambridge also embodies the tensions of modern Massachusetts: hyper-educated and wealthy alongside working-class and immigrant, with housing costs that exclude the middle class entirely.

The Coastal Communities

Massachusetts’ coastal towns range from working ports to tourist havens, often combining both identities uneasily. Gloucester remains a working fishing port, though tourism increasingly drives its economy. The city’s fishermen, immortalized in “The Perfect Storm,” represent a dying breed, but the harbor still bustles with boats heading out to the fishing grounds.

Provincetown, at Cape Cod’s tip, has evolved from fishing village to artist colony to LGBTQ haven. Summer sees the year-round population of 3,000 swell to 60,000. P-town, as locals call it, embodies coastal Massachusetts’ transformation: still salty, increasingly expensive, balancing preservation with change.

The Suburbs

Between city and country lies suburban Massachusetts, neither urban nor rural but something distinctly its own. The Route 128 belt (Lexington, Concord, Weston, Wellesley) houses some of the nation’s wealthiest communities. These towns perfect a New England aesthetic: white churches on town greens, stone walls, careful zoning that maintains a rural feel despite proximity to Boston.

Further out, places like Framingham and Natick represent a different suburbia: more diverse, more middle class, more likely to have strip malls than village greens. These communities, once bedroom towns, increasingly function as employment centers themselves, part of the state’s polycentric development.

Small Towns and Rural Massachusetts

Beyond the suburbs, rural Massachusetts persists, though it’s a different rural than Vermont or New Hampshire. The hill towns of the Berkshires maintain Yankee traditions, though gentrification creeps in as New Yorkers buy second homes. Towns like Shelburne Falls and Cummington attract artists and back-to-the-landers, creating curious cultural hybrids.

In central Massachusetts, small towns like Barre and Petersham seem caught in time, their commons unchanged since the 19th century. These places struggle with aging populations and limited economic opportunities, yet maintain a stubborn vitality. Town meetings still decide important issues, volunteer fire departments still respond to calls, and everyone still knows everyone else’s business.

Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

The Transcendentalist Revolution

No discussion of Massachusetts culture can ignore the extraordinary literary flowering that occurred in 19th-century Concord. He remains among the linchpins of the American romantic movement, and his work has greatly influenced the thinkers, writers, and poets that followed him. “In all my lectures,” he wrote, “I have taught one doctrine, namely, the infinitude of the private man.” Emerson is also well-known as a mentor and friend of Henry David Thoreau, a fellow Transcendentalist. Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 25, 1803, to Ruth Haskins and the Rev. William Emerson, a Unitarian minister.

These Concord writers were: Henry David Thoreau Louisa May Alcott Nathaniel Hawthorne Ralph Waldo Emerson William Ellery Channing. The writers wrote many famous books, essays and poems and had a significant impact on literature in the 19th century. As a result, they have often been compared to another famous literary group, the Bloomsbury Group of London, so much so that a book was even written about them in recent years titled American Bloomsbury. Much like the London Bloomsbury Group, the Concord writers had a shared set of values, morals, beliefs and a shared appreciation for art and literature. They were abolitionists, transcendentalists, nature lovers as well as writers and poets.

‘Authors Ridge’ at Sleepy Hollow cemetary.

Emily Dickinson’s Amherst

While Concord claimed the Transcendentalists, Amherst produced perhaps America’s greatest poet. Born roughly a generation after Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, and Henry D. Thoreau, Dickinson was a child when the Transcendental club was meeting regularly and just fourteen years old when The Dial published its last issue in 1844. Along with many of her Transcendentalist precursors, the Amherst-born Dickinson challenged the dogmatic religious doctrine that suffused the atmosphere of her upbringing and education.

The shy, home-centered Emily Dickinson was fascinated with the sensational newspapers of the time. The war years (1861-1865) opened up complex and existential questions for Dickinson, which led to her most prolific period: of her nearly 1,800 poems, approximately half were written during those years. Skepticism and musings on death and the afterlife permeated her work.

The Boston Brahmins

Boston’s literary culture produced its own aristocracy, the Boston Brahmins. Oliver Wendell Holmes (who coined the term), James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. These writers, often Harvard-educated and independently wealthy, created a genteel tradition that dominated American letters through the 19th century.

Their influence extended beyond literature into shaping Boston’s cultural institutions. The Boston Public Library, the Boston Athenaeum, the Atlantic Monthly magazine, all bore the Brahmin stamp. They believed in literature’s civilizing mission, in culture as moral improvement.

Modern Literary Legacy

Massachusetts continues to nurture writers, though the scene has democratized and diversified. Dennis Lehane’s crime novels capture working-class Boston with unsentimental accuracy. Junot Díaz writes about Dominican immigrant experience in Lawrence. The poetry scene thrives in Cambridge and Somerville coffeehouses.

The state’s universities function as literary incubators. The MFA programs at Emerson College, Boston University, and UMass Amherst train new generations of writers. Literary magazines proliferate. Independent bookstores, despite economic pressures, survive in numbers unusual for 21st-century America.

Visual Arts

Massachusetts’ visual arts tradition stretches from colonial limners to contemporary installations. The Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum anchor Boston’s art scene, but smaller institutions throughout the state preserve important collections.

The Berkshires have become a particular arts destination. Mass MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) in North Adams occupies a former factory complex, transforming industrial ruins into exhibition space. In the town of North Adams, MASS MoCA (Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art) beckons art enthusiasts with its sprawling campus housed within a renovated industrial complex. Here, visitors can explore cutting-edge exhibitions and installations amidst the backdrop of historic mill buildings.

Music and Performance

From the Boston Symphony Orchestra to underground punk clubs, Massachusetts supports diverse musical traditions. Tanglewood, the BSO’s summer home in the Berkshires, draws classical music lovers from around the world. Jazz flourished in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. Folk music found homes in Cambridge clubs like Club 47 (now Club Passim).

The state’s musical contributions extend to popular music. Aerosmith, the Cars, and the Pixies all emerged from the Boston scene. More recently, the city has produced indie bands and hip-hop artists who draw on local experiences while reaching global audiences.

Architectural Heritage

Massachusetts architecture tells the story of American building. First Period houses from the 1600s still stand, their massive central chimneys and small windows designed for harsh winters. Georgian and Federal styles followed, reaching perfection in Salem’s McIntire Historic District and Boston’s Beacon Hill.

The industrial age brought innovation. H.H. Richardson’s Trinity Church in Boston pioneered the Richardsonian Romanesque style. The Boston Public Library exemplified the American Renaissance. Modern architects from Walter Gropius to I.M. Pei left their marks on the state’s built environment.

Yet Massachusetts’ most characteristic architecture might be vernacular: the triple-deckers of Worcester and Somerville, the fish houses of Gloucester, the saltboxes of Cape Cod. These buildings, designed for use rather than show, express the state’s practical Yankee character.

Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

The Sea’s Bounty

The first time I tasted authentic New England clam chowder on a foggy Boston morning, I knew other soups would forever pale in comparison. This creamy, soul-warming concoction combines tender clams, potatoes, and onions in a rich, velvety broth that practically screams Massachusetts. Unlike Manhattan’s red version (don’t even mention that around here!), our white chowder has been comforting locals since the 1700s. Fresh quahogs and salt pork that create an unmistakable flavor profile. Served with oyster crackers for the perfect textural contrast, this hearty staple appears on menus from upscale restaurants to weathered fishing shacks. During winter months, nothing beats clutching a steaming bowl while watching waves crash against Cape Cod’s shoreline.

The lobster roll represents Massachusetts coastal cuisine at its most iconic and contentious. My first memorable lobster roll came from a weathered shack in Gloucester. I remember chunks of sweet, tender lobster meat barely bound together with mayonnaise, a hint of lemon, and nothing else to mask that ocean-fresh flavor. The toasted, buttered split-top roll provided the perfect vehicle for this simple luxury. Summer tourists willingly wait in hour-long lines for these treasures, but locals know the best spots. The astronomical price tag (some now fetch $30+) hasn’t dampened enthusiasm for this iconic treat that transforms humble street food into something sublime.

Classic New England lobster roll

Cranberry Culture

Long before that familiar can-shaped cylinder graced Thanksgiving tables nationwide, Massachusetts residents were cooking down their native cranberries into tangy-sweet sauce. I’ve trudged through cranberry bogs during harvest season, marveling at how these ruby gems float to the surface when the bogs flood. While many Americans only enjoy cranberry sauce during holiday feasts, Bay Staters incorporate it year-round. We spread it on sandwiches, swirl it into yogurt, or serve it alongside cheese plates. That sweet-tart punch cuts through rich foods perfectly, explaining why it’s stood the test of time.

Massachusetts produces about 23% of the nation’s cranberries, with bogs concentrated in the southeastern part of the state. The autumn harvest, when bogs flood and berries float in crimson seas, has become a tourist attraction in its own right.

Beyond the Sea

Not all Massachusetts cuisine comes from the ocean. The state’s inland traditions reflect its agricultural past and immigrant influences. Apple orchards dot the landscape, particularly in the nashoba Valley, producing fruit for eating, baking, and cider-making. The state’s craft cider renaissance builds on centuries of tradition.

Parker House rolls, invented at Boston’s Parker House Hotel, gave America a dinner-table staple. Boston cream pie, despite its name, is actually a cake and the official state dessert. Indian pudding, a molasses-sweetened cornmeal dessert, connects to colonial foodways.

Immigrant Influences

Each wave of immigration added flavors to Massachusetts cuisine. The Irish brought corned beef and cabbage (though in Ireland, it was bacon and cabbage). Italians transformed the North End into a Little Italy where you can still find handmade pasta and cannoli. Portuguese immigrants in New Bedford and Fall River contributed linguiça sausage and malasadas.

More recent immigrants continue the evolution. Brazilian churrascarias thrive in Framingham. Cambodian restaurants in Lowell serve num pang sandwiches. Chinese communities have moved beyond Chinatown to establish restaurants in Quincy and Malden that rival any in the country.

The Modern Food Scene

Contemporary Massachusetts dining reflects both tradition and innovation. Chefs embrace local sourcing, connecting with fishermen, farmers, and foragers. The farm-to-table movement found eager adoption here, building on existing connections between producers and consumers.

Yet traditionalists need not worry. You can still find perfect fried clams in Essex, Italian subs in the North End, and roast beef sandwiches on the North Shore. These foods, unglamorous but beloved, represent Massachusetts cuisine as much as any haute cuisine creation.

Drinks and Drinking Culture

Massachusetts drinking culture begins with history. This is where American brewing began, where rum distilling fueled the Triangle Trade. Samuel Adams beer takes its name seriously, and craft breweries proliferate throughout the state.

The state’s bar culture reflects its Irish influence. Boston claims to have more bars per capita than any other American city, though the math is disputed. Neighborhood pubs anchor communities, serving as informal town halls where politics, sports, and gossip mix freely.

Coffee culture thrives, particularly in Boston and Cambridge. Dunkin’ (formerly Dunkin’ Donuts), founded in Quincy, represents one end of the spectrum: quick, unpretentious, ubiquitous. At the other end, third-wave coffee shops in Somerville and Jamaica Plain treat coffee as seriously as wine.

Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

A Highway of History

U.S. Route 1 (US 1) is a major north–south U.S. Route that runs from Key West, Florida to Fort Kent, Maine. In the state of Massachusetts, it travels through Essex, Middlesex, Suffolk, Norfolk, and Bristol counties. The portion of US 1 south of Boston is also known as the Boston–Providence Turnpike, Washington Street, or the Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike, and portions north of Boston are known as the Northeast Expressway and the Newburyport Turnpike.

Route 1 in Massachusetts tells the story of American transportation evolution. What began as Native American paths became colonial post roads, then turnpikes, and finally modern highways. The route’s path through the state reveals layers of history at every mile.

Share your Massachusetts route 1 memory

Do you have a story you would like to share? We want to hear it!

Create a View to tell a unique story about a specific place

Want to see what others wrote about Massachusetts?

Our Travel map has over 1400 posts from users like you

We have 2 types of content at Route1views:

- View: A unique experience at a single location

- Trip: A collection of experiences at different places, connected through a ‘road trip’

- Most first-time posters choose to make a View

A note about Route 1 Views

We are a user-driven social media site for celebrating and sharing stories along historic Route 1 USA. Using our platform is FREE forever and we don’t play any tricks. We don’t share your data or spam you with emails. We are all about sharing!

Southern Section: Mill Towns and Suburbs

From the south, US 1 enters Massachusetts from Rhode Island, immediately entering the city of Attleboro. It closely parallels Interstate 95 (I-95) as it goes through the towns of North Attleborough, Plainville, Wrentham, Foxborough (where Gillette Stadium is), Walpole, Sharon, Norwood, and Westwood.

This southern stretch passes through communities that exemplify Massachusetts’ evolution from agriculture to industry to suburbia. Attleboro, once “The Jewelry Capital of the World,” still maintains some manufacturing, though much has moved overseas. Foxborough hosts the New England Patriots, representing the state’s modern entertainment economy.

The road here often follows ancient paths. In Sharon, Route 1 follows the old Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike route, where mile markers from the turnpike era occasionally surface during construction projects. These towns, once distinct villages separated by farmland, now blur together in continuous development.

Through Boston: The Modern Merge

US 1 then has a wrong-way concurrency with I-95 up to the interchange that is the southern terminus of I-93. US 1 then travels concurrently with I-93 from Canton through Downtown Boston; Route 3 joins the concurrency in Braintree. In Downtown Boston, Route 1A and Route 3 separate from US 1 to head toward Logan International Airport and Cambridge respectively, and I-93 and US 1 separate just after passing through the O’Neill Tunnel and crossing the Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge.

The route’s passage through Boston represents the modern reality of urban highways; elevated, tunneled, complex with interchanges. The Big Dig transformed this section, burying the formerly elevated Central Artery and creating the Rose Kennedy Greenway above.

The Northeast Expressway

North of Boston, Route 1 becomes the Northeast Expressway, a 1950s-era highway that exemplifies mid-century planning. US 1 continues north, crossing the Tobin Bridge as the Northeast Expressway and traveling through Chelsea, Revere, and Malden, then as a four- to six-lane expressway through Saugus, Lynnfield, and Peabody.

This section includes some of Massachusetts’ most distinctive roadside architecture. The Hilltop Steak House’s giant cactus sign in Saugus became an icon before the restaurant’s closure. The orange dinosaur of the Route 1 Miniature Golf in Saugus remains a beloved landmark. These kitschy attractions represent an era when highways were adventures, not just commutes.

The North Shore Journey

From Peabody, US 1 again closely parallels I-95 going through the towns of Danvers, Topsfield, Ipswich, Rowley, Newbury, and Newburyport. In Newburyport, US 1 has a mile-long (1.6 km) freeway segment that bypasses downtown and the waterfront areas; Route 1A joins the freeway shortly before it crosses the Merrimack River, entering Salisbury and becoming a surface arterial again. Three miles (4.8 km) later, it enters the state of New Hampshire.

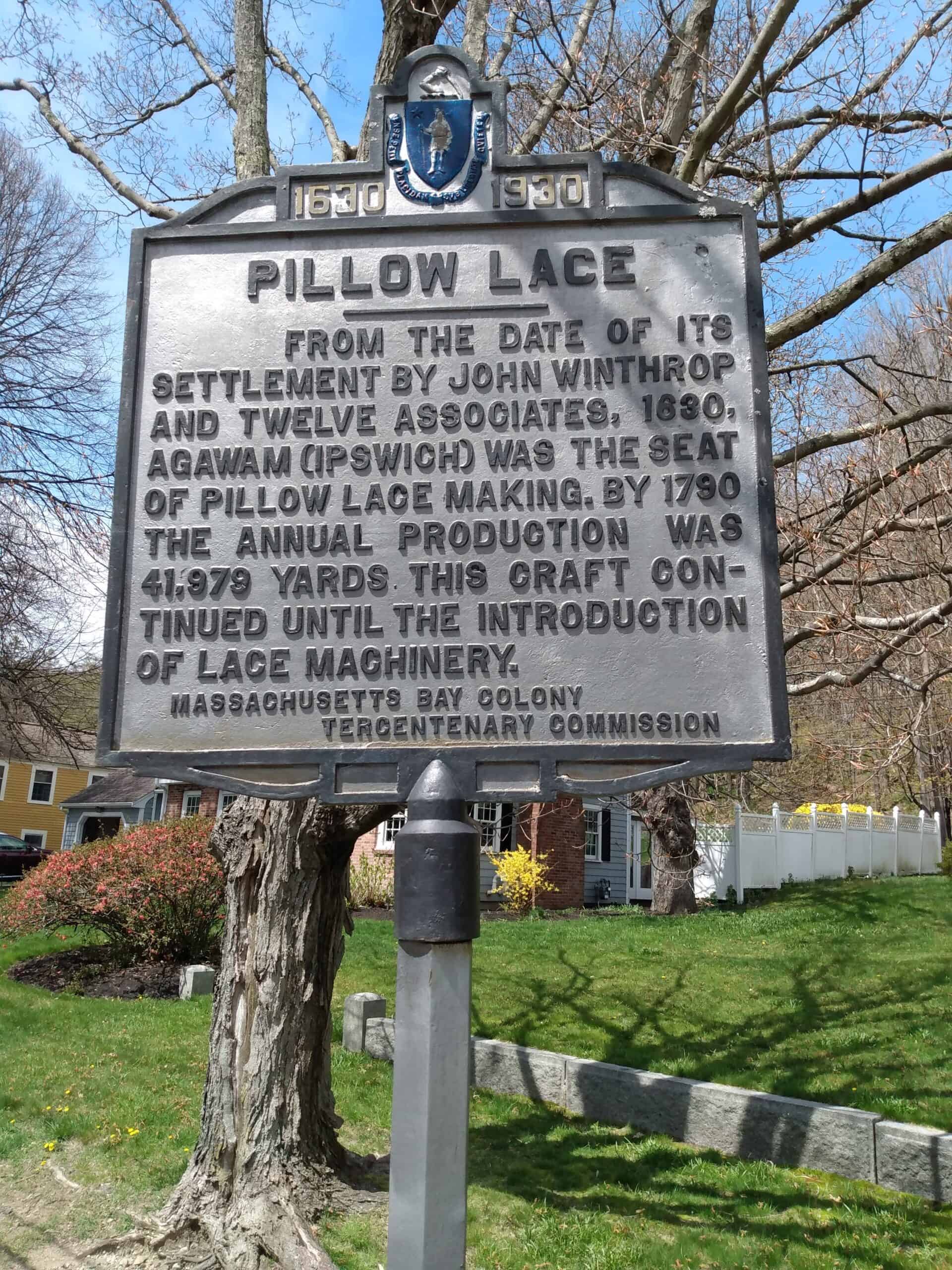

This northern section passes through some of Massachusetts’ most historic territory. Ipswich claims more First Period houses than any other community in America. Newburyport, once one of America’s great shipbuilding centers, has transformed into a perfectly preserved Federal-era city that attracts tourists and Boston commuters alike.

Route 1A: The Scenic Alternative

This segment of Route 1A extends from Boston, Massachusetts to Salisbury, Massachusetts. The highway starts from US 1 (which is on the Central Artery with I-93 and Route 3) at the former Government Center/Logan Airport interchange. It passes through the Callahan Tunnel (outbound/northbound) and Sumner Tunnel (inbound/southbound), becoming the East Boston Expressway past Logan Airport. Immediately beyond Logan Airport, Interstate 90 ends at Route 1A.

Route 1A offers the scenic alternative, hugging the coast through Revere Beach (America’s first public beach), Lynn, Swampscott, and Marblehead. This route serves beach communities and yacht clubs, passing through landscapes that inspired the American maritime painting tradition.

Stories from the Road

Every stretch of Route 1 tells stories. In Saugus, the Iron Works represents the beginning of American industry. In Newburyport, grand Federal mansions speak to the wealth generated by the China trade. In Revere, the beach that once hosted elaborate amusement parks now serves new immigrant communities who gather for family barbecues where Yankee families once changed in Victorian bath houses.

The highway itself has stories. Older residents remember when Route 1 was the main road to New Hampshire and Maine before I-95’s construction. They recall the traffic jams on summer Fridays, the restaurants and motor courts that served travelers, the sense that a trip up Route 1 was an adventure.

Modern Challenges

Today, Route 1 faces the challenges of aging infrastructure and changing transportation patterns. Work would also include reconstruction of the Copeland Circle interchange by eliminating the existing rotary, and demolition of the existing 1957 bridges from the never-built highway extension. The Lynn Street/Salem Street interchange in Malden, and the Route 99 interchange in Saugus, were slated to be reconstructed. Major rock blasting would be required for the project due to a massive ledge next to the highway, and seven bridges would be replaced and three others upgraded to handle the new lanes. In 2012, $10 million (equivalent to $13.1 million in 2023) was added to the state budget with the intent to be used for design costs and pulling permits for US 1. The project was expected to begin in 2012, but no further movement by the state has been implemented. Since then, town officials have made the push to ask MassDOT to revisit the project and begin development.

Historic markers along Route 1 in Ipswich

Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

Beyond the Tourist Trail

While visitors flock to Salem’s witch museums and Plymouth’s Mayflower II, Massachusetts residents know the state’s real treasures lie off the beaten path. These places don’t appear in most guidebooks, discovered through word-of-mouth or happy accident.

Natural Wonders

In North Adams, you’ll find this hidden gem! Naturally formed white marble arch housed in an abandoned marble quarry from the 1800s. It is estimated that the arch formed by Hudson Brook is 550 million years old. The Natural Bridge State Park represents the kind of geological wonder that Massachusetts does quietly. No fanfare, just ancient rock and rushing water creating something magnificent.

Visitors to the Quabbin can enjoy a variety of activities, including hiking, fishing, birdwatching, and wildlife photography. With over 200 miles of shoreline and miles of wooded trails to explore, this hidden gem offers endless opportunities for adventure and exploration. The Quabbin Reservoir, created by flooding four towns in the 1930s, offers an eerie beauty. The foundations of the drowned towns sometimes appear during droughts, and the protected watershed has become an inadvertent wilderness preserve.

Forgotten History

Occupying 150 acres of a 914-acre wide expanse of Massachusetts’ Rutland State Park, Rutland Prison Camp was established in 1903 as a means to provide shelter to minor offenders and put them to work on the prison farm that grew potatoes and cultivated poultry. An initiative to keep the likes of drunkards and such petty criminals, Rutland’s prison farm was known to produce enough milk to sell to Worchester. Aside from the farm, the Prison Camp also housed cell blocks, staff quarters, a water tower, and a tuberculosis treatment center which was added in 1907. Unfortunately, the Prison was constructed on a drainage area for the water supply in the area which led to its closure in 1934. All that remains now are the dilapidated ruins of what used to be the famous Rutland Prison Farm, but, the area is still is great for explorers and hikers.

As the story goes, the 71-year-old woman was accused of witchcraft by the local Putnam family who had a longstanding land feud with the Nurses. Rebecca was found not guilty at first, but, a reconsideration made the judge change his verdict and sentence her to death. The mother of eight received a proper Christian burial by her family and was buried on the land, which is now the burial ground for several witchcraft victims in the area, including George Jacobs who was accused and executed exactly after a month from Rebecca. The Rebecca Nurse Homestead in Danvers (originally Salem Village) offers a more authentic witch trial experience than Salem’s commercialized attractions.

Artistic Surprises

In the village of Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, a bridge is groomed to bloom beautifully with flowers all summer long. It is a 400-foot long bridge covered in flowers expertly planted to ensure they bloom continuously from April to October. The bridge includes 500 varieties of flowers, vines, and shrubs. Worth the walk across. Please don’t pick the flowers, and enjoy the fragrance. Really unusual and unique bridge.

You may or may have never noticed this piece of art when you walked past it all those times, but, this graffiti-covered walkway in Central Square that connects the City Parking Lot 5 to Massachusetts Avenue is way more than just another boardwalk. Partially decorated with a colorful plastic canopy resembling a “stained glass”, the Richard B. “Rico” Modica Way is a public pathway as well as a 24-hour open-air art gallery. Simply known as the Modica Way, the gallery, on one side, houses a black and white pictorial collage of people and places around Central Square – an installation by the city. The other, however, is set aside for graffiti artists who are free to spray paint the walls with their creativity and imagination.

Gardens and Quiet Spaces

Located in the Back Bay Fens section of the Emerald Necklace, this whimsical garden features over 200 varieties of rose bushes. Despite being close to Boylston Street, Fenway Park, and the Museum of Fine Arts, this gem feels like a secret garden untouched by its urban neighbors. Featuring a formal landscape style design with symmetrical pathways, statues, a fountain, and arched trellises, the garden takes you back in time and is the perfect escape from the hustle and bustle of urban life. Although the rose garden is a peaceful sanctuary anytime it is open, we recommend visiting from late June to Labor Day.

One of the best-kept secrets in Massachusetts is hidden on Martha’s Vineyard’s Chappaquiddick Island. Here you can find the breathtaking Mytoi Japanese Gardens. Tranquility awaits you as you meander through paths among native and exotic plants.

Architectural Oddities

This architectural marvel was built by hand over 120 years ago and is located in Worcester’s Salisbury Park. More information about this hidden gem can be found on the City Of Worcester Salisbury Park website. The Bancroft Tower, a miniature castle overlooking Worcester, offers panoramic views and Gothic romance without the tourist crowds.

A historic bridge in Newton with a lovely acoustic anomaly. A platform that was built specifically for visitors to play around with this aural anomaly can be found at the bottom of a set of stairs that lead underneath the bridge. An impressive echo that returns up to 15 reverberations of the human voice, and a loud, sharp sound such as a pistol shot can repeat as many as 25 times.

Local Knowledge

The best hidden gems often aren’t places but experiences known only to locals. The perfect fried clam shack that only opens May through September. The beach access road that doesn’t appear on GPS. The hillside where you can watch the sunrise over the Atlantic. The restaurant in Lawrence where Dominican grandmothers make sancocho that transports you to the Caribbean.

Massachusetts residents guard these secrets carefully, sharing them selectively. It’s not unfriendliness but preservation as too much attention ruins what makes these places special. The overcrowded lobster shack was once someone’s secret spot. The quiet pond discovered by kayakers becomes a parking nightmare once it appears on social media.

Seasonal Secrets

Some hidden gems reveal themselves seasonally. Ok, call me crazy but I seriously thought this was just on a TV commercial for Cranberry Juice! Cranberry Bogs are actually all over MA. If you want to visit a Cranberry Bog, just find one near the area you’re going to be in. I found about 13 in the state but I’ll bet there are more.

The cranberry harvest in October transforms southeastern Massachusetts into a photographer’s dream, with flooded bogs creating mirrors of crimson.

Vernal pools appear in spring, hosting salamander migrations that few witness. Beach plum blossoms cover the dunes in May. October brings not just legendary foliage but also the alewife runs, when ancient fish return to freshwater streams, following instincts older than human memory.

Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

The Housing Crisis

Massachusetts faces a housing affordability crisis that threatens its future vitality. Median home prices in Greater Boston exceed $700,000. Young families, essential workers, and middle-class professionals find themselves priced out. The state that educated them can’t house them.

The crisis reflects success turned pathological. Good schools and job opportunities attract residents, driving up prices. Restrictive zoning preserves community character but prevents new construction. NIMBY attitudes clash with desperate need. Communities that pride themselves on progressivism resist the density that could make housing affordable.

Climate Change Impacts

It shows that Massachusetts is getting warmer, leading to more options for gardeners, but also more risks of invasive plants and bugs.

Rising seas threaten coastal communities. Boston has ambitious resilience plans, but smaller coastal towns lack resources for major adaptations. Fishing communities watch species migrate north as waters warm. The state’s famous fall foliage arrives later and lacks the vivid colors that drive tourism.

Extreme weather events increase. The blizzards of 2015 shut down Boston’s transit system for weeks. Flooding that once occurred rarely now happens regularly. Infrastructure designed for a different climate struggles to cope.

2015 Storm Juno caused major disruptions in Boston

Economic Transitions

The knowledge economy that saved Massachusetts from deindustrialization creates new vulnerabilities. Biotech and tech companies cluster in Cambridge and Boston, but automation threatens even white-collar jobs. The state’s high costs drive companies to consider alternatives. Remote work, accelerated by COVID-19, allows knowledge workers to leave while keeping their jobs.

Gateway Cities still struggle to find their place in the new economy. Some, like Lowell, have reinvented themselves through arts and education. Others remain stuck, their downtowns empty, their young people leaving, their tax bases eroding.

Demographic Shifts

Population growth during this period, which was aided by immigration from abroad, helped in urbanization and forced a change in the ethnic make-up of the Commonwealth. The largely industrial economy of Massachusetts began to falter, however, due to the dependence of factory communities upon the production of one or two goods. External low-wage competition, coupled with other factors of the Great Depression in later years, led to the collapse of the state’s two main industries: shoes and textiles.

Massachusetts ages as young people leave and birth rates fall. The state depends on immigration to maintain population, but federal policies create uncertainty. New immigrants cluster in Gateway Cities, revitalizing neighborhoods but straining services.

The state’s racial dynamics evolve. The Boston of busing riots seems distant, but segregation persists in subtler forms. Suburban communities remain overwhelmingly white while cities diversify. The state’s progressive self-image clashes with persistent inequalities.

Transportation and Infrastructure

Massachusetts’ infrastructure shows its age. The MBTA, North America’s oldest subway system, struggles with maintenance backlogs. Highways designed for 1950s traffic volumes clog daily. The state that pioneered American transportation now exemplifies its decay.

Yet opportunities exist. The state’s compact size makes it ideal for public transit and alternative transportation. Bike lanes proliferate in Cambridge and Somerville. Regional rail proposals could transform suburbs. The challenge is funding and political will.

Educational Excellence Under Strain

Massachusetts’ excellent schools face new pressures. Achievement gaps persist between rich and poor districts. The cost of maintaining excellence grows while resistance to taxes remains strong. Charter schools divide communities. The state that leads national rankings worries about keeping its edge.

Higher education faces its own challenges. Small colleges close or merge. Even prestigious institutions face financial pressure. International students, crucial to university finances, face visa restrictions. The model of ever-rising tuition meets its limits.

The Path Forward

Despite challenges, Massachusetts retains fundamental strengths. Its educated workforce, world-class institutions, and innovative culture provide resilience. The state has reinvented itself before, from maritime power to industrial giant to knowledge economy leader.

The future likely requires another reinvention. Perhaps Massachusetts becomes a leader in climate adaptation, turning necessity into opportunity. Maybe it solves the housing crisis through innovative development models. The state’s history suggests it will find a way forward, though the path remains unclear.

Enduring Character

Whatever changes come, certain elements of Massachusetts character seem likely to endure. The pride in education and intellectual achievement. The tension between tradition and innovation. The local loyalties that make someone from Worcester bristle at being called a Bostonian. The conviction, sometimes warranted, sometimes not, that Massachusetts does things better than other places.

The state remains what it has always been: small in size, large in impact, confident in purpose, anxious about position. It’s a place where history lives alongside innovation, where town meetings coexist with biotech labs, where fishermen and professors share (sometimes uneasily) the same commonwealth.

Massachusetts continues to punch above its weight, contributing ideas, innovations, and arguments to the national conversation. It remains, in its own mind at least, that city upon a hill that its Puritan founders envisioned, though transformed in ways they could never have imagined.

This is Massachusetts: keeper of memories, incubator of futures, a small state with an outsized sense of self. It frustrates and inspires, welcomes and excludes, looks backward and forward simultaneously. Understanding it requires accepting these contradictions, recognizing that they’re not flaws but features of a place that has always contained multitudes within its modest borders.