The Granite State's Enduring Identity

New Hampshire

In a nation of superlatives, New Hampshire occupies a unique position: small in size but outsized in influence, traditional yet progressive, fiercely independent yet deeply connected to its neighbors. This is a state where presidential candidates still shake hands at diners, where ancient granite mountains meet Atlantic waves, and where the motto “Live Free or Die” isn’t just engraved on license plates but embedded in the collective psyche.

The Granite State, as it’s affectionately known, may rank 46th in size among the 50 states, but its impact on American politics, culture, and identity far exceeds its modest 9,351 square miles. From the revolutionary raids on Fort William and Mary to today’s first-in-the-nation presidential primary, New Hampshire has consistently punched above its weight, shaping national conversations while maintaining its distinctly local character.

Table of Contents

- Geography & Natural Landscape

- Historical Timeline & Key Events

- Share your New Hampshire route 1 memory

- Cultural Identity & Regional Character

- Economy & Industry Evolution

- Politics & Governance

- Cities, Towns & Population Centers

- Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

- Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

- Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

- Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

- Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

Geography & Natural Landscape

The Granite Foundation

New Hampshire ranks 46th in terms of size, covering just 9,351 square miles yet within this compact territory lies an remarkable diversity of landscapes that would be impressive in a state twice its size. Contained within the Appalachian Highlands, the three primary geological features and landforms (physiographic regions) of New Hampshire are; the Coastal Lowlands, the Eastern New England Upland, and the White Mountain Region

The state’s geological story begins with New Hampshire is nicknamed the Granite State because it has a history of granite mining. This granite foundation, formed millions of years ago, provides both the literal bedrock and metaphorical backbone of the state’s character. The granite isn’t merely decorative, it has shaped everything from architecture to agriculture, creating both opportunities and challenges that have molded the New Hampshire way of life.

Mountains That Touch the Sky

The crown jewel of New Hampshire’s geography lies in the north, where the forested White Mountains in the north include Mount Washington. At 6,288 feet tall, this is New England’s highest point

Mount Washington isn’t just a geographic landmark, it’s a meteorological phenomenon. The greatest climatic extremes occur on the summit of Mount Washington, the site of a noted weather observatory. On April 12, 1934, the observatory there recorded a world-record wind speed of 231 miles (372 km) per hour

With hurricane-force winds every third day on average, more than a hundred recorded deaths among visitors, and conspicuous krumholtz (dwarf, matted trees much like a carpet of bonsai trees), the climate on the upper reaches of Mount Washington has inspired the weather observatory on the peak to claim that the area has the “World’s Worst Weather”

The White Mountains region extends far beyond Mount Washington, encompassing White Mountain National Forest constitutes more than one-tenth of the state’s area and is almost uninhabited

This vast wilderness provides both ecological sanctuary and economic opportunity through tourism and recreation.

The Symbolic Stone Face

For generations, the White Mountains were home to the rock formation called the Old Man of the Mountain, a face-like profile in Franconia Notch, until the formation disintegrated in May 2003. Even after its loss, the Old Man remains an enduring symbol for the state, seen on state highway signs, automobile license plates, and many government and private entities around New Hampshire

The loss of the Old Man of the Mountain was more than geological; it was cultural. This granite profile, which had watched over the state for millennia, represented the enduring, stoic character that New Hampshire residents see in themselves.

Water Features and Valleys

Major rivers include the 110 mile (177 km) Merrimack River, which bisects the lower half of the state north-south and ends up in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Its major tributaries include the Contoocook River, Pemigewasset River, and Winnipesaukee River. The 410 mile (670 km) Connecticut River, which starts at the Connecticut Lakes and flows south into Connecticut, defines the western border with Vermont

The lakes region around Lake Winnipesaukee (the state’s largest lake) serves as both a natural playground and economic engine for the state. These water features have historically provided power for mills and continue to offer recreational opportunities that draw visitors from across New England.

The Mighty Monadnock

In the southwestern corner, the landmark Mount Monadnock has given its name to a class of earth-forms – a “monadnock” – signifying, in geomorphology, any isolated resistant peak rising from a less resistant eroded plain. Mount Monadnock, one of the world’s most-climbed mountains!

This accessibility has made it a hiking destination for generations and a symbol of New Hampshire’s outdoor culture.

Climate Patterns and Seasonal Rhythms

New Hampshire experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa in some southern areas, Dfb in most of the state, and Dfc subarctic in some northern highland areas), with warm, humid summers, and long, cold, and snowy winters

Summers are relatively cool, and the mean annual temperature is about 44 °F (7 °C). Annual precipitation is approximately 42 inches (1,070 mm) and is rather evenly distributed over the four seasons. Average snowfall is about 50 inches (1,270 mm) along the coast and 100 inches (2,540 mm) in the northern and western parts of the state

This climate creates the conditions for New Hampshire’s legendary fall foliage, ski industry, and seasonal tourism patterns that drive much of the state’s economy.

The Seacoast: Small but Mighty

With only 13 miles of coastline, the New Hampshire coastline is shorter than any other state that borders an ocean

Yet this brief encounter with the Atlantic Ocean packs considerable punch. The Coastal Lowlands cover the southeastern corner of the state, where it touches the Atlantic Ocean. Here you can find sandy beaches along the coastline and wetlands farther inland

Historical Timeline & Key Events

Indigenous Foundations

Long before European ships appeared on the horizon, people lived in what’s now New Hampshire at least 12,000 years ago. Thousands of years later Native American tribes, including the Abenaki and the Pennacook, lived on the land

They were organized into clans, semiautonomous bands, and larger tribal entities; the Pennacook, with their central village in present-day Concord, were by far the most powerful of these tribes. The entire Native American population was part of the linguistically unified Algonquian culture that dominated northeastern North America. Tribes living in New Hampshire were mostly of the Algonquian group called the western Abenaki

These indigenous peoples left an indelible mark on the landscape, with the primary contemporary reminder of Native American inhabitation is in place-names such as Lake Winnipesaukee, Kancamagus Highway, and Mount Passaconaway. French and English explorers began to arrive in the 1500s, and the English established the first permanent European settlement in 1623

The New Hampshire Colony was one of the 13 original colonies of the United States and was founded in 1623. The land in the New World was granted to Captain John Mason, who named the new settlement after his homeland in Hampshire County, England

The early settlements faced numerous challenges. Fish, whales, fur, and timber were important natural resources for the New Hampshire colony. Much of the land was rocky and not flat, so agriculture was limited. For sustenance, settlers grew wheat, corn, rye, beans, and various squashes

Revolutionary Fires

New Hampshire’s role in the American Revolution began before most Americans had even heard of Lexington and Concord. On December 13, 1774, four months before his famous “midnight ride” to Lexington, Massachusetts, Paul Revere embarked on a 55-mile ride from Boston to Portsmouth to warn of Fort William and Mary’s imminent seizure from British troops. In one of the first acts of rebellion leading up to the revolution, a group of nearly 400 townspeople responded by raiding the garrison’s gunpowder to prevent the takeover, lowering the fort’s British flag upon their return to Portsmouth

Although there were apparently no casualties, these were among the first shots in the American Revolutionary period, occurring approximately five months before the Battles of Lexington and Concord This bold action established New Hampshire’s reputation for taking the lead in challenging authority. In 1776, New Hampshire became the first colony to establish its own constitutional government, effectively declaring independence from Great Britain

Even more significantly, At the war’s end, New Hampshire was the ninth and deciding state to ratify the United States Constitution. On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state in the Union

Industrial Transformation

The 19th century brought dramatic change to New Hampshire. Industrialization in New Hampshire took the form of numerous textile mills that attracted large flows of immigrants from Quebec (the “French Canadians”) and Ireland Manchester’s Amoskeag Manufacturing Company became the largest textile mill in the world

This industrial boom reshaped not just the economy but the demographics and culture of the state, bringing in waves of immigrants who would become integral to New Hampshire’s identity.

20th Century Transitions

The textile industry that had defined New Hampshire for decades began to collapse after World War II. After 1960, the textile industry collapsed, but the economy rebounded as a center of high technology and as a service provider

This transition from an industrial to a post-industrial economy required considerable adaptation and innovation from New Hampshire residents and businesses.

Share your New Hampshire route 1 memory

Do you have a story you would like to share? We want to hear it!

Create a View to tell a unique story about a specific place

Want to see what others wrote about New Hampshire?

Our Travel map has over 1400 posts from users like you

We have 2 types of content at Route1views:

- View: A unique experience at a single location

- Trip: A collection of experiences at different places, connected through a ‘road trip’

- Most first-time posters choose to make a View

A note about Route 1 Views

We are a user-driven social media site for celebrating and sharing stories along historic Route 1 USA. Using our platform is FREE forever and we don’t play any tricks. We don’t share your data or spam you with emails. We are all about sharing!

Cultural Identity & Regional Character

The “Live Free or Die” Mentality

New Hampshire’s motto, “Live Free or Die”, reflects its role in the American Revolutionary War. This isn’t mere historical nostalgia: it represents a living philosophy that shapes contemporary political and social life. Central to that identity is the image of governmental frugality: New Hampshire has no general sales tax or individual income tax

The motto stems from General John Stark’s toast before the Battle of Bennington, and it encapsulates an individualistic spirit that distinguishes New Hampshire from its neighbors. This independence manifests in various ways, from the state’s unique tax structure to its insistence on maintaining the first-in-the-nation primary.

Town Meeting Democracy

Frugality at the state level has accentuated the dispersal of responsibility to towns. Although town governments exist in all the New England states, in no state do they carry as much authority nor as much responsibility for providing their own services as in New Hampshire

This localized approach to governance reflects the state’s deep skepticism of centralized power and its faith in community-level decision-making.

Regional Distinctions

New Hampshire boasts a rich tapestry of distinct regions, each deeply rooted in the state’s history and shaping unique local cultures within its broader identity. The heavily forested White Mountains area in the north attracts outdoor enthusiasts and tourists alike, fostering a culture centered around recreation, environmental stewardship, and seasonal tourism.

The lakes region around Lake Winnipesaukee, favored for summer camps, resorts, and aquatic sports, embodies a more relaxed, vacation-oriented lifestyle. The Seacoast region, encompassing Portsmouth, Dover, Exeter, and Hampton, thrives on maritime activities, while the south-central Merrimack region, surrounding Manchester and Nashua, stands as the state’s most industrialized hub.

The Persistence of Tradition

Still another component of that identity is a craggy adherence to tradition, long powerfully symbolized by the rock profile in Franconia Notch known as the Old Man of the Mountain; the rock outcropping collapsed in 200. Even after its physical disappearance, the Old Man continues to represent New Hampshire’s stubborn loyalty to its roots and reluctance to change for change’s sake.

Religious and Cultural Diversity

The state’s religious landscape reflects its historical development. Before the Revolution, New Hampshire religion was dominated by Congregationalism, the faith of the colony’s Puritan founders. Virtually every New Hampshire town contained at least one organized Congregationalist parish, its minister supported by public tax monies

Over time, this religious homogeneity gave way to greater diversity, particularly as immigrant populations brought different faiths and traditions to the state.

Economy & Industry Evolution

From Mills to Microchips

New Hampshire’s economic story is one of remarkable transformation. New Hampshire experienced a major shift in its economic base during the 20th century. Historically, the base was composed of traditional New England textiles, shoemaking, and small machine shops, drawing upon low-wage labor from nearby small farms and parts of Quebec. Today, of the state’s total manufacturing dollar value, these sectors contribute only two percent for textiles, two percent for leather goods, and nine percent for machining

This transformation didn’t happen overnight. During the 1950s New Hampshire’s economy slowly began to turn around. As older textile mills and shoe factories disappeared, new companies making machinery, precision instruments, electrical products, and, eventually, computers and computer accessories replaced them

The Modern Economic Landscape

Today’s New Hampshire economy is remarkably diverse. At this point, a few industries act as main drivers for the state’s economy: Smart Manufacturing/High Technology (SMHT): SMHT is the largest and most important sector of the state’s economy. New Hampshire’s SMHT sector is mainly known for using high-tech equipment to produce electronic components. In 2009, the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy studies found SMHT accounted for 19 percent of wages paid in the state

The geographic distribution of this economic activity reflects the state’s regional diversity. Much of the SMHT activity is concentrated along the Seacoast and in the Upper Valley. The Merrimack Valley and Monadnock Region also host a number of manufacturing operations

Tourism: The Second Pillar

Tourism is New Hampshire’s second-largest industry if you combine the state’s smart manufacturing and high technology sectors (SMHT). New Hampshire welcomes 10 million visitors a year, creating opportunities to collaborate and contribute the dynamic travel and hospitality industry

New Hampshire has traditionally depended on its natural resources and recreational opportunities to draw in out-of-state visitors throughout the year. The Seacoast, Lakes Region, and White Mountains are the primary tourism hotspots.

Recent data shows the importance of this sector: Today, the New Hampshire Division of Travel and Tourism Development announced new records set during New Hampshire’s fall 2021 tourism season, during which New Hampshire saw a 38% increase in visitors from the previous record year (2019), with 4.3M visitors traveling to the Granite State. Spending by visitors in New Hampshire reached nearly $2 billion – a 65% increase from 2019.

Economic Resilience and Prosperity

Despite its small size, New Hampshire has built a remarkably resilient economy. The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that New Hampshire’s total state product in 2018 was $86 billion, ranking 40th in the United States. Median household income in 2017 was $74,801, the fourth highest in the country (including Washington, DC).

The state’s unique tax structure contributes to this prosperity. It is one of nine states without an income tax and has no taxes on sales, capital gains, or inheritance while relying heavily on local property taxes to fund education; consequently, its state tax burden is among the lowest in the country.

Employment Patterns

The New Hampshire economy comprises more than 750,000 jobs of all types, and New Hampshire residents work in a diverse set of industries. Most of us both live and work in New Hampshire, but, as of 2017, 19 percent (roughly 123,500 people) of New Hampshire workers commuted to jobs in other states, with most of them (97,000) employed in Massachusetts.

This commuter pattern reflects New Hampshire’s position within the broader New England economy, particularly its proximity to the Boston metropolitan area.

Politics & Governance

First in the Nation

Perhaps no aspect of New Hampshire’s identity is more nationally recognized than its presidential primary. The New Hampshire presidential primary is the first in a series of nationwide party primary elections and the second party contest, the first being the Iowa caucuses, held in the United States every four years as part of the process of choosing the delegates to the Democratic and Republican national conventions which choose the party nominees for the presidential elections to be held in November.

New Hampshire state law provides: “The presidential primary election shall be held on the second Tuesday in March or on a date selected by the secretary of state which is 7 days or more immediately preceding the date on which any other state shall hold a similar election, whichever is earlier.” New Hampshire has closely guarded its “first primary in the nation” status through this provision. The state has held the first primary in each presidential campaign since 1920.

The Politics of Independence

New Hampshire’s official motto “live free or die” goes back to the Civil War and the state has a famous independent streak. Today, nearly 40% of its voters are undeclared. Undeclared voters can walk up on Tuesday’s primary and vote for whichever party or candidate they like, and first-time voters can also show up and register on Election Day.

This independent streak manifests in voting patterns that don’t always align with national trends. The New Hampshire primary is a semi-open primary: unaffiliated voters (those registered without party affiliation) may vote in either party’s primary. Voters registered with one party cannot “cross vote” to vote in another party’s primary.

Retail Politics and Personal Engagement

New Hampshire is known for its retail politics — at diners, community meetings and town halls, fielding questions directly from the public — which Galdieri said can be critical for candidates who are lesser known to nonetheless breakthrough on the national stage.

This tradition of personal political engagement reflects the state’s broader cultural values of accessibility, directness, and skepticism of political hierarchies.

The Weight of Small Numbers

New Hampshire only has 22 delegates, roughly half of Iowa, which has 40. Both of those numbers are a fraction of huge, diverse states like California, Florida, New York and Texas. Republican candidates have to collect a total of at least 1,215 delegates to clinch the nomination. “The number of delegates that you win coming out of New Hampshire is irrelevant,” said Conroy. “What matters is exceeding expectations. Getting the media narrative and the wind in your sails … people, generally, like winners in politics.”

Cities, Towns & Population Centers

Portsmouth: The Historic Seaport

Portsmouth stands as New Hampshire’s most historically significant city, a place where one of the greatest port cities of the 18th and early 19th century, which still has a working waterfront, along with a vibrant and historic downtown. During the colonial period, the seat of government was at Portsmouth, and there were 147 chartered towns in the province.

Portsmouth’s historic district preserves much of its colonial and Federal period architecture, while its modern restaurant scene has gained national recognition. The city successfully balances preservation with progress, maintaining its maritime character while embracing contemporary economic opportunities.

Manchester: The Queen City

Manchester is the most populous city in New Hampshire. Built around the massive Amoskeag Mills complex, Manchester became the heart of New Hampshire’s industrial economy. Though the mills closed decades ago, the city has successfully reinvented itself as a center for higher education, healthcare, and technology.

The Millyard, once the world’s largest textile manufacturing complex, now houses a diverse mix of businesses, from high-tech startups to healthcare facilities. This adaptive reuse represents Manchester’s broader ability to honor its industrial heritage while embracing new economic realities.

Concord: The Capital’s Quiet Authority

Its capital is Concord, and Concord is the capital city of New Hampshire and the county seat of Merrimack County. Settled between 1725 and 1727 by Captain Ebenezer Eastman and others from Haverhill, Massachusetts, it was incorporated as Rumford. Following a bitter boundary dispute between Rumford and the town of Bow, it was renamed Concord in 1765 by Governor Benning Wentworth.

In the years following the American Revolution, Concord’s central geographical location made it a logical choice for the state capital, particularly after Samuel Blodget in 1807 opened a canal and lock system to allow vessels passage around the Amoskeag Falls downriver, connecting Concord with Boston by way of the Middlesex Canal. In 1808, Concord was named the official seat of state government.

The State House was built in 1819, and still stands, making New Hampshire’s legislature the oldest state government in the U.S.

Nashua: The Southern Gateway

Nashua represents New Hampshire’s integration with the broader Boston metropolitan economy. Its location near the Massachusetts border makes it attractive to businesses and residents who want access to Boston-area opportunities while enjoying New Hampshire’s tax advantages and quality of life.

Regional Population Patterns

Of the 50 U.S. states, New Hampshire is the seventh-smallest by land area and the tenth-least populous, with a population of 1,377,529 residents as of the 2020 census. This relatively small population is distributed unevenly across the state, with the southern tier containing the majority of residents due to its proximity to Massachusetts employment centers.

The demographic trends show both opportunity and challenge. By the 1960s New Hampshire had become one of the fastest-growing states east of the Mississippi River; the population roughly doubled between the 1960 and 2000 censuses. However, this growth has been concentrated in certain regions, leaving rural areas facing population decline and economic challenges.

New Hampshire state capital

Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

Literary Traditions

New Hampshire has produced and inspired numerous notable writers and artists. The state’s natural beauty and independent spirit have long attracted creative individuals seeking both inspiration and the freedom to pursue their artistic visions without the pressures of urban life.

The fictional New Hampshire town of Grover’s Corners serves as the setting of the Thornton Wilder play Our Town. Grover’s Corners is based, in part, on the real town of Peterborough. Several local landmarks and nearby towns are mentioned in the text of the play, and Wilder himself spent some time in Peterborough at the MacDowell Colony, writing at least some of the play while in residence there.

The MacDowell Colony, a residential retreat in Peterborough for artists, has hosted countless writers, composers, and visual artists over more than a century. This institution represents New Hampshire’s ongoing commitment to supporting the arts and providing creative individuals with the space and time they need to develop their work.

Architectural Heritage

New Hampshire’s architectural landscape tells the story of its development from colonial settlement to modern state. Colonial and Federal period buildings in Portsmouth showcase the wealth and sophistication of early maritime commerce. The massive mill complexes in Manchester and other industrial cities demonstrate the ambition and engineering prowess of the 19th century industrial era.

Rural New Hampshire preserves countless examples of vernacular architecture: farmhouses, barns, and village buildings that reflect the practical needs and aesthetic sensibilities of agricultural communities. These structures, often built with local materials including granite and timber, demonstrate the close relationship between New Hampshire’s natural resources and its built environment.

Contemporary Arts Scene

Modern New Hampshire supports a diverse array of artistic endeavors. Regional theaters, galleries, and music venues provide platforms for both local and visiting artists. The state’s natural beauty continues to inspire painters, photographers, and other visual artists, while its small towns and independent spirit attract writers and musicians seeking authenticity and community.

MacDowell Colony artist studio, NH

Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

Apple Cider Donuts: The Quintessential Treat

Perhaps no food item better represents New Hampshire’s culinary identity than the apple cider donut. At New Hampshire’s pick-your-own farms, fall festivals, and general stores across the state, apple cider donuts are fried up to a golden crisp and served warm. These are not your donut-chain donuts with pink frosting, jelly infusions, and colored sprinkles. Like Granite Staters, apple cider donuts are subtly sweet, understated, and if done right, just a little bit crusty. They’re made with apple cider, cinnamon, and nutmeg.

Apple cider donuts have been served during harvest time since New Hampshire was a colony when there were plenty of apples and fat to fry them in from the fall harvest of farm animals. While these delicious treats were invented in New York. But New Hampshire is home to the best version of this delicacy, and there is still one place that offers them year-round.

Maple Syrup: Liquid Gold

This decadent drink is made from homemade vanilla ice cream and real New Hampshire maple syrup. No one knows for sure, but Parker’s Maple Barn in Mason has been serving them since they opened in 1969. New Hampshire’s maple syrup has a rich, sweet, and slightly smoky flavor profile, with undertones of caramel and vanilla. This unique flavor comes from the sap of the state’s sugar maple trees that is harvested and boiled down to create the syrup.

The maple syrup industry represents both tradition and innovation in New Hampshire. Modern maple producers use sophisticated evaporation systems and quality control methods while maintaining the essential connection to the land and seasonal rhythms that have defined the industry for centuries.

Franco-American Influences

Many of New Hampshire’s iconic dishes are the food of the working class; recipes brought down from Canada to the mills, hearty, tasty, and enough calories to get you through a 12-hour shift at the textile factory. This includes dishes like gorton, a savory spread made with pork, pork fat, milk, bread crumbs, and spices is often eaten with toast and mustard for breakfast. Think of it as a kind of Franco-American pâté. Gorton came straight from Canada down to New Hampshire.

The spread had its start in the monasteries of Quebec and seems to have its etymological roots in the medieval French word, “creton” meaning a small piece of fat

Seacoast Specialties

Portsmouth clam chowder festival.

Despite having only 13 miles of coastline, New Hampshire has developed a distinctive seafood culture. Seafood, particularly clam chowder, is a staple along the coastline, with spots in Portsmouth known for serving it fresh and creamy. Lobster rolls, served either cold with mayonnaise or warmed with butter, showcase the freshness of local catches. Clam chowder, another staple, emphasizes the state’s seafood excellence, particularly when enjoyed near the ports where the day’s catch is brought in.

Agricultural Heritage

Other treats derive from our geography: lush apple orchards, tall maple trees, and hardscrabble farms. Its agricultural outputs are dairy products, nursery stock, cattle, apples and egg. New Hampshire’s maple syrup is a renowned product, with the state’s sugar maples providing a bountiful source. In addition to syrup, dairy farming is a cornerstone of local agriculture, producing high-quality dairy goods including cheese and yogurt. Noteworthy among the dairy producers is Stonyfield, an organic yogurt company with national distribution.

Traditional New England Fare

These molasses bars are as New England as food can get. They’re made with ingredients you could have found in Colonial New Hampshire, including molasses, dried fruit, and warm spices like ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon, and clove. New Hampshire is well known for its “boiled dinner”, which is usually ham or corned beef boiled with potatoes, carrots, and cabbage.

Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

The Historic Highway

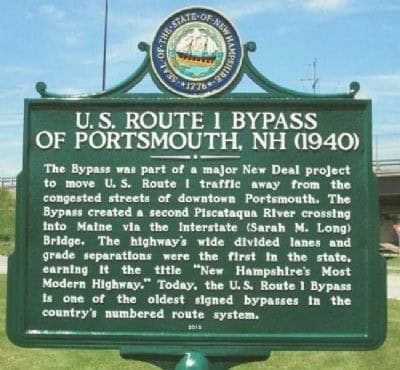

Route 1 in New Hampshire may be brief (The route closely parallels I-95 along Lafayette Road for a majority of its 17-mile (27 km) stretch in the state) but it serves as a vital connector between Massachusetts and Maine while threading through some of the state’s most historically significant and economically important communities.

U.S. Route 1 (US 1) is a north–south U.S. Route is the U.S. state of New Hampshire through Hampton and Portsmouth. US 1 begins in Seabrook at the border with Salisbury, Massachusetts. US 1 travels through Hampton, North Hampton, and finally enters Portsmouth.

Communities Along the Route

As Route 1 enters New Hampshire from Massachusetts, it immediately encounters Seabrook, a community known for both its nuclear power plant and its extensive salt marshes. The route then continues through Hampton, where it passes near Hampton Beach, one of New Hampshire’s premier tourist destinations.

Moving north through North Hampton, Route 1 provides access to some of New Hampshire’s most beautiful coastal areas and historic sites. The route serves both local traffic and the thousands of visitors who come to experience New Hampshire’s seacoast region.

The northern terminus of Route 1 in New Hampshire is Portsmouth, where US 1 travels down State Street going toward Maine and Market Street into Portsmouth. Portsmouth represents the culmination of Route 1’s journey through New Hampshire, offering both historical significance and modern amenities.

The Coastal Connection

Route 1 provides access to one of New Hampshire’s most scenic drives. When the sun’s out, there’s nothing like rolling the windows down and taking a drive along Route 1A. Unlike many of the scenic routes outlined in our recent guide to the best New England summer drives, the New Hampshire seacoast is only 13 miles long, meaning this drive can be as short or as long as you want.

While Route 1 itself runs slightly inland, it connects to Route 1A, which provides the actual coastal experience that draws visitors from across New England.

Economic Significance

Route 1 serves as more than just a transportation corridor: it’s an economic lifeline for the seacoast region. The highway provides access to beaches, restaurants, shops, and attractions that form the backbone of the area’s tourism industry. It also connects residential communities with employment centers and essential services.

Historical Importance

The Route 1 corridor has been a pathway for centuries, following routes used by indigenous peoples and early European settlers. During the colonial period, this route connected New Hampshire’s seacoast communities with the broader Atlantic world through maritime trade.

During the Revolutionary War, this corridor saw significant military activity, including the famous raid on Fort William and Mary. The route continues to serve as a connector between New Hampshire and its neighbors, facilitating the movement of people, goods, and ideas that have shaped the state’s development.

Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

Off-the-Beaten-Path Natural Wonders

While Mount Washington draws the crowds, locals know about less-traveled peaks like Mount Cardigan and Mount Kearsarge, which offer spectacular views with fewer fellow hikers. The Flume Gorge in Franconia Notch provides a dramatic natural experience, but nearby Diana’s Baths offers equally stunning waterfalls with better opportunities for solitude.

Castle in the Clouds, a mountaintop mansion overlooking Lake Winnipesaukee, combines architectural marvel with natural beauty. Built in the early 20th century, it represents the era when wealthy industrialists sought refuge in New Hampshire’s mountains.

Cultural Treasures

The Canterbury Shaker Village preserves not just buildings but an entire way of life. The Shakers, though not native to New Hampshire, gathered substantial numbers of converts to their charismatic, celibate, and communitarian Societies at Canterbury and Enfield. Today, visitors can experience the Shakers’ remarkable craftsmanship, innovative technology, and spiritual philosophy.

Strawbery Banke Museum in Portsmouth has 32 historic buildings where people can watch costumed performers act out life from colonial times. This living history museum provides an immersive experience of New Hampshire’s seacoast heritage.

Culinary Discoveries

Beyond the famous apple cider donuts, New Hampshire harbors numerous culinary secrets. Small-town general stores often serve as unofficial community centers, offering everything from locally-made preserves to hand-cut steaks. The 187-year-old Harrisville General Store exemplifies this tradition.

Local farms throughout the state offer pick-your-own opportunities that extend far beyond apples: strawberries, blueberries, pumpkins, and Christmas trees provide seasonal experiences that connect visitors directly with New Hampshire’s agricultural heritage.

Artisan Communities

Small towns throughout New Hampshire host artists and craftspeople who create everything from traditional pottery to contemporary sculptures. These artisans often welcome visitors to their studios, providing opportunities to see traditional crafts being practiced and to purchase unique, locally-made items.

The state’s numerous antique shops reflect both New Hampshire’s long history and its residents’ reluctance to discard quality items. These establishments often function as informal museums, preserving artifacts that tell the story of local and regional history.

Seasonal Celebrations

While fall foliage season draws millions of visitors, locals know that each season offers its own rewards. Winter brings opportunities for cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and ice fishing. Spring offers maple sugaring season, when many sugarhouses welcome visitors to observe the syrup-making process.

Summer brings county fairs that preserve agricultural traditions while providing contemporary entertainment. These events showcase everything from draft horse competitions to quilting demonstrations, offering authentic experiences of rural New Hampshire culture.

Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

Demographic Pressures

New Hampshire faces the demographic challenges common to much of rural New England: an aging population, out-migration of young people, and declining birth rates. These trends threaten the vitality of rural communities and strain public services designed for younger, larger populations.

The state’s success in attracting high-income residents and businesses helps offset some of these challenges but also creates new ones, including housing affordability and income inequality. As property values rise, long-term residents sometimes find themselves priced out of communities where their families have lived for generations.

Economic Diversification

While New Hampshire has successfully transitioned from a manufacturing-based economy to one centered on technology and services, continued economic diversification remains essential. And although manufacturing is still an important part of New Hampshire’s economy, advances in technology and the decline of traditional fabrication work all over the country means factories employ far fewer people than in the past.

Toward the end of the 20th century, Massachusetts became a center for high-tech sectors. And in turn, New Hampshire has been able to piggy-back off its neighbor’s success, moving its economy toward electronic component manufacturing and other high-tech industries.

The challenge lies in maintaining this competitive advantage while developing new economic sectors that can provide opportunities for residents with varying skill levels and educational backgrounds.

Environmental Concerns

Climate change poses particular challenges for New Hampshire’s tourism-dependent economy. Winter season lengths are projected to decline at ski areas across New Hampshire due to the effects of climate change, which is likely to continue the historic contraction and consolidation of the ski industry and threaten individual ski businesses and communities that rely on ski tourism.

The state must balance economic development with environmental protection, particularly as pressure for development increases in previously undeveloped areas. Water quality, forest health, and wildlife habitat all face pressures from both climate change and human development.

Infrastructure and Transportation

New Hampshire’s location between Boston and the rest of New England creates both opportunities and challenges. The state benefits from proximity to major metropolitan areas but must manage increasing traffic and pressure on infrastructure. Maintaining and improving roads, bridges, and other infrastructure requires continued investment and planning.

The challenge of providing adequate internet connectivity to rural areas remains significant, particularly as remote work becomes more common and essential for economic development.

Political Evolution

Not only has the state’s economy diversified, but its politics has as well. Although New Hampshire traditionally had been a Republican state beginning a few years after the formation of the party (by politicians including Exeter’s Amos Tuck) in the 1850s, the Democratic Party made a resurgence in the 1960s, resulting in the election of Democratic governors as well as U.S. congressmen and senators.

The state’s political future will likely depend on its ability to maintain its distinctive political culture while adapting to changing demographics and economic conditions. The first-in-the-nation primary remains a source of national attention and economic benefit, but its future depends on the state’s ability to maintain broad support for this tradition.

Preserving Identity

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing New Hampshire is maintaining its distinctive identity while adapting to 21st-century realities. The values that have defined the state (independence, frugality, local control, and connection to the land) must evolve to address contemporary challenges without losing their essential character.

This requires careful balance: embracing beneficial change while preserving what makes New Hampshire unique. The state’s success in this endeavor will determine whether future generations can experience the same sense of place and community that has defined New Hampshire for more than four centuries.

New Hampshire’s story continues to unfold, shaped by the same forces that have always defined it: the interplay between tradition and innovation, the tension between independence and community, and the enduring influence of its granite foundations and mountain horizons. In a rapidly changing world, the Granite State’s challenge is to remain true to its essential character while writing new chapters worthy of its remarkable past.

Whether measured by its outsize political influence, its economic resilience, its natural beauty, or its cultural contributions, New Hampshire proves that significance isn’t always measured in size. In this small state where neighbors still gather at town meetings and presidential candidates still answer questions at diners, the American experiment in democracy and community continues to evolve, one person and one conversation at a time.