Beyond the Turnpike - An Insider's Guide to the Garden State

New Jersey

New Jersey suffers from an image problem. Sandwiched between New York City and Philadelphia, it’s often dismissed as a mere corridor, a place you pass through rather than visit. The jokes write themselves: industrial wastelands, aggressive drivers, reality TV caricatures. But those who know New Jersey – really know it – understand that these stereotypes mask one of America’s most complex, historically rich, and surprisingly beautiful states.

This is a state that gave us both Thomas Edison and Bruce Springsteen, Princeton University and the Pine Barrens, revolutionary battlefields and Atlantic City casinos. It’s where colonial history meets cutting-edge pharmaceuticals, where millionaire horse farms border struggling post-industrial cities, where you can surf at dawn and ski by afternoon. Understanding New Jersey requires looking past the exhaust fumes of the Turnpike to discover why locals fierce defend their state with an intensity that outsiders often mistake for mere defensiveness.

Table of Contents

- Geography & Natural Landscape

- Historical Timeline & Key Events

- Cultural Identity & Regional Character

- Economy & Industry Evolution

- Politics & Governance

- Cities, Towns & Population Centers

- Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

- Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

- Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

- Share your New Jersey route 1 memory

- Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

- Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

Geography & Natural Landscape

The Four Jerseys

Geographers divide New Jersey into four distinct regions, though locals will argue there are dozens more. The Highlands in the northwest feature ancient ridges and valleys carved by glaciers, creating a landscape more reminiscent of Vermont than the typical Jersey stereotype. Here, black bears outnumber traffic lights, and the Appalachian Trail winds through 72 miles of protected forests.

New Jersey Highlands

Moving south, the Piedmont region encompasses most of northern and central Jersey, a gently rolling landscape that proved perfect for the suburban sprawl that followed World War II. This is where geology meets demography: the easily developed land between the ridges became the template for American suburbanization.

The Inner Coastal Plain, stretching from Trenton to the Pine Barrens, tells the story of an ancient seabed. Sandy soils here supported the colonial iron industry and later gave rise to the cranberry bogs and blueberry farms that still dot the landscape. The Outer Coastal Plain includes the barrier islands and beaches that draw millions of summer visitors, though year-round residents know these shores have a melancholy beauty in winter that summer tourists never see.

The Pine Barrens Phenomenon

Perhaps no feature defines New Jersey’s hidden character quite like the Pine Barrens, 1.1 million acres of protected pine and oak forests sitting atop one of North America’s largest aquifers. Known officially as the Pinelands National Reserve, this ecosystem seems almost supernatural in its persistence. Despite being surrounded by the most densely populated region in America, the Pine Barrens remain largely as they were three centuries ago.

The sandy, acidic soil that deterred farmers created a unique ecology. Carnivorous plants thrive in the nutrient-poor bogs. The pygmy pine plains, where mature trees stand just four feet tall due to frequent fires and poor soil, create an almost alien landscape. Beneath it all, the Kirkwood-Cohansey aquifer holds 17 trillion gallons of some of the purest water in the nation: a resource more valuable than oil in the coming century.

Climate as Destiny

New Jersey’s position at the climatic crossroads of America shapes more than just the weather forecast. The state sits precisely where the hot, humid subtropical climate of the South meets the cold continental climate of the North. This convergence creates the conditions for nor’easters that can dump three feet of snow, summer thunderstorms that light up the sky like artillery barrages, and perfect autumn days that make even the most jaded resident fall in love with the state again.

The moderate climate (harsh enough to build character but mild enough to attract settlers) helped make New Jersey the crossroads of colonial America. Today, climate change poses new challenges: more frequent flooding along the coast, hotter summers stressing the electrical grid, and unpredictable storms that catch even seasoned residents off guard.

Historical Timeline & Key Events

Before the Europeans

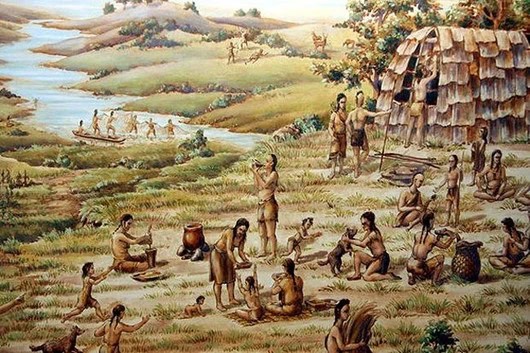

The Lenni-Lenape people lived in what would become New Jersey for thousands of years before European contact. Their three main groups (the Munsee in the north, Unami in the central region, and Unalachtigo in the south) created a sophisticated society based on seasonal migration between the shore and inland areas. Their trail system became the template for many modern roads, including parts of Route 1.

Colonial Crossroads (1609-1776)

Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage up the river that would bear his name opened New Jersey to European colonization, but the state’s split personality began almost immediately. The Dutch claimed the north while the Swedes established New Sweden along the Delaware River in the south. When the English took control in 1664, they divided the territory between two proprietors, creating East and West Jersey: a division whose cultural echoes persist today.

The colonial period established New Jersey’s fundamental character as a place between places. Positioned between the major ports of New York and Philadelphia, New Jersey became the corridor through which goods, people, and ideas flowed. This geographic destiny created a practical, entrepreneurial culture that valued commerce over ideology.

Revolutionary Proving Ground (1776-1783)

No state saw more Revolutionary War action than New Jersey. Washington crossed the Delaware on Christmas night 1776 to attack Trenton, then won again at Princeton a week later, victories that saved the Revolution when it seemed lost. The state earned the nickname “Crossroads of the Revolution” as armies crisscrossed its territory throughout the war.

Recreation of Washington Crossing the Delaware

The war’s impact went beyond battles. The constant presence of both armies (and the divided loyalties of residents) created a rougher, more pragmatic political culture than in states where the conflict was more distant. New Jersey developed a tradition of political flexibility that sometimes shaded into corruption but also allowed for surprising progressivism.

Industrial Pioneer (1790-1900)

Alexander Hamilton’s vision of American manufacturing came to life first in Paterson, where the Great Falls of the Passaic River provided power for the nation’s first planned industrial city. The “Silk City” would later produce locomotives, textiles, and Colt revolvers. Thomas Edison made Menlo Park the “invention factory” where he developed the light bulb, phonograph, and motion picture camera.

The pharmaceutical industry deserves special mention. New Jersey boasts a robust biopharmaceutical manufacturing industry, with eight out of the top 10 pharmaceutical companies in the world having a significant presence in the state. Key players such as Johnson & Johnson, Merck & Co., Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Novartis, and Teva established roots here in the early 20th century, drawn by proximity to New York’s financial markets, skilled immigrant labor, and favorable patent laws.

The Modern Era (1900-present)

The 20th century brought waves of transformation. The opening of the Holland Tunnel in 1927 and the George Washington Bridge in 1931 accelerated suburbanization. The Garden State Parkway (1957) and the New Jersey Turnpike (1951) created the modern commuter culture that defines much of the state today.

World War II transformed New Jersey into the “Arsenal of Democracy.” Shipyards in Camden and Newark built vessels for the war effort. Fort Dix trained hundreds of thousands of soldiers. The war’s end brought the GI Bill and massive suburban expansion, turning farms into subdivisions at a breathtaking pace.

The late 20th century saw deindustrialization hit hard. Cities like Newark, Camden, and Paterson lost manufacturing jobs and middle-class residents to the suburbs. In the past 20 years, New Jersey went from having more than 20 percent of U.S. pharma manufacturing jobs to less than 10 percent. Yet this period also saw the rise of the corporate campus, the birth of the McMansion, and the transformation of Jersey Shore towns from working-class retreats to wealthy enclaves.

Cultural Identity & Regional Character

The Geography of Identity

Ask a New Jerseyan where they’re from, and they’ll likely define themselves by their proximity to either New York or Philadelphia: or by their exit on the Turnpike. This divided loyalty reflects a deeper truth: New Jersey has never been one unified culture but rather a collection of distinct regions, each with its own character.

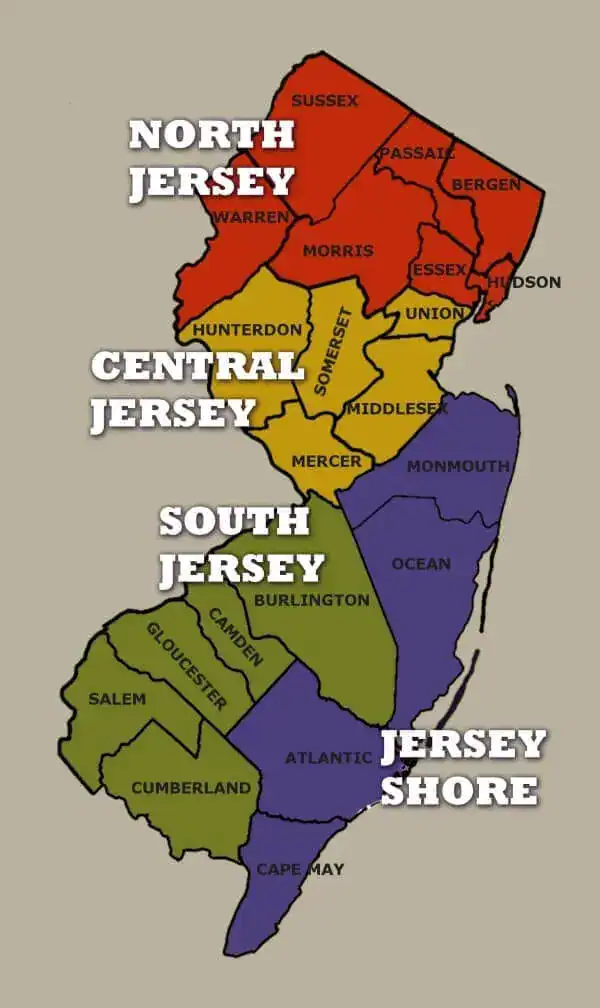

North Jersey operates in New York’s orbit, with commuters streaming into Manhattan daily. The pace is faster here, the accents sharper, the ambitions perhaps grander. Central Jersey (whose very existence is debated with theological intensity) serves as a transitional zone, mixing elements of both its neighbors. South Jersey, oriented toward Philadelphia, moves at a different rhythm, with a culture more rooted in agriculture and the shore.

New Jersey’s regional divisions

The Diner State

If New Jersey has a sacred space, it’s the diner. With more diners per capita than any other state, these 24-hour restaurants serve as democratic meeting grounds where construction workers share counter space with surgeons, where high school kids plot their futures over disco fries at 2 AM.

The diner represents New Jersey’s working-class soul: unpretentious, practical, always open. The menu, encyclopedic in scope, mirrors the state’s diversity. You can order a Taylor ham (never “pork roll” in the north) sandwich, Greek moussaka, or Jewish matzo ball soup, often from the same kitchen. This culinary democracy extends beyond diners to the state’s food culture generally: New Jersey perfected the art of the strip mall ethnic restaurant, where sublime Pakistani cuisine might share a parking lot with exceptional Korean barbecue.

The Shore Thing

The Jersey Shore isn’t just a geographic feature: it’s a state of mind. From Sandy Hook to Cape May, 130 miles of beaches have shaped the state’s summer culture for over a century. Each beach town has its own personality: Spring Lake’s Irish Riviera gentility, Asbury Park’s bohemian revival, Wildwood’s retro kitsch, Atlantic City’s faded glamour.

The Shore teaches harsh lessons about impermanence. Hurricane Sandy in 2012 devastated communities that had weathered storms for a century. The rebuilding that followed revealed both the fragility of coastal development and the fierce attachment residents feel to these barrier islands. The Shore’s seasonal rhythm (frantic summers, quiet winters) creates a unique culture among year-round residents who treasure the off-season’s solitude.

Attitude as Identity

The New Jersey attitude (direct, skeptical, impatient with pretense) is both stereotype and survival mechanism. In a state where you’re always from somewhere else originally, where you’re constantly defending your home against tired jokes, a certain defensiveness develops. But this manifests as a fierce pride among natives, who know their state’s worth even if outsiders don’t.

This attitude appears in the state’s humor which is self-deprecating but protective, quick to mock itself but quicker to defend against outside mockery. It’s in the driving culture, where aggressive merging is considered a courtesy (you’re keeping traffic moving) and hesitation is the only real sin. It’s in the political culture, where retail politics still matters and town council meetings can turn into blood sport over seemingly minor issues.

Economy & Industry Evolution

From Manufacturing to Meds

New Jersey’s economic transformation mirrors America’s, but with distinctive twists. The state that once produced everything from silk to submarines had to reinvent itself as factories closed. New Jersey has a long history of being a leader in pharmaceutical innovation. The history of the state goes back to the 1800s, and it has always been at the forefront of medical development.

Today’s economy rests on several pillars: pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, financial services, telecommunications, and logistics. The Port of Newark-Elizabeth remains one of the busiest on the East Coast. The state’s location (within a day’s drive of one-third of the U.S. population) makes it invaluable for distribution centers.

The Corporate Campus Revolution

The 1960s and 1970s saw New Jersey pioneer the corporate campus concept. Companies fled Manhattan’s costs for New Jersey’s space, creating self-contained worlds in places like Murray Hill (Bell Labs), Basking Ridge (AT&T), and Morris Plains (Honeywell). These campuses, set in former farmland, offered a new vision of work-life balance: or at least work-life proximity.

The model worked until it didn’t. Telecommuting, corporate consolidation, and changing worker preferences have left many campuses empty or underutilized. The 116-acre corporate campus of the Swiss drugmaker Roche in Nutley, N.J… since December, all of that space (2 million square feet of it) has been vacant, the laboratories dark and the sidewalks deserted.

The challenge now is reimagining these spaces for a new economy.

The Innovation Ecosystem

Despite setbacks, New Jersey maintains significant innovative capacity. Princeton University anchors a research corridor. Rutgers, the state university, has emerged as a major research institution. Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken specializes in engineering and technology. The state’s educated workforce (among the highest percentages of advanced degrees in the nation) attracts companies needing skilled labor.

But the state also maintains traditional industries that outsiders rarely consider. According to the USDA’s most recent Census of Agriculture, there are 9,998 farms in New Jersey with a market value of agricultural products sold totaling nearly $1.5 billion.

The Garden State moniker isn’t just marketing: Food and agriculture is the third largest industry in New Jersey, behind only pharmaceuticals and tourism. Cranberries from the Pine Barrens, tomatoes from South Jersey, corn from Hunterdon County: the state feeds the megalopolis that surrounds it.

Politics & Governance

The Machine and the Reformer

New Jersey politics operates on contradiction. It’s simultaneously one of the most progressive states (with strong environmental laws, generous social programs, and civil rights protections) and one of the most notorious for political corruption. This paradox reflects the state’s divided soul: high-minded idealism coexisting with brass-knuckle pragmatism.

The political machine tradition, imported from big cities, found fertile ground in New Jersey’s fragmented geography. With 565 municipalities, 21 counties, and countless special districts, the state created infinite opportunities for patronage and deal-making. The phrase “honest graft” (coined by New York’s George Washington Plunkitt but perfected in New Jersey) captures the ethic: taking care of your people while taking care of yourself.

Home Rule Religion

New Jersey’s devotion to home rule borders on religious fervor. Each municipality jealously guards its independence, creating a Byzantine system of overlapping jurisdictions. This fragmentation drives up property taxes (consistently among the nation’s highest) but residents accept this as the price of local control.

The result is a state where neighboring towns might have wildly different tax rates, school systems, and services. A street can mark the boundary between excellent schools and struggling ones, between low crime and high, between well-maintained infrastructure and decay. This hyper-localism creates stark inequalities but also allows for experimentation and diversity in governance.

The Moderate Tradition

Despite its Democratic lean in recent decades, New Jersey maintains a moderate political culture. Governors from both parties have succeeded by tacking to the center. The state’s Republicans tend toward the Rockefeller wing: fiscally conservative but socially moderate. Democrats range from machine politicians to progressive reformers, but extreme positions rarely succeed statewide.

This moderation stems partly from the state’s economic interdependence with its neighbors. Policies that might drive businesses to Pennsylvania or New York face immediate scrutiny. The state’s educated, affluent population demands competent governance more than ideological purity. Even Chris Christie, who cultivated a national reputation as a conservative firebrand, governed largely as a moderate on state issues.

Cities, Towns & Population Centers

Newark: Renaissance and Reality

Newark, New Jersey’s largest city, embodies the state’s struggles and potential. Once a thriving industrial center, Newark suffered catastrophic decline after the 1967 riots. White flight, deindustrialization, and disinvestment left the city with a reputation for crime and dysfunction that persisted for decades.

Today’s Newark tells a more complex story. The downtown has genuinely revived, with new residential towers, a thriving arts district, and the Prudential Center drawing crowds. Newark Liberty International Airport remains a major economic engine. Rutgers-Newark and NJIT bring young energy to the city. Yet beyond downtown, many neighborhoods still struggle with poverty, crime, and decades of neglect. The renaissance is real but incomplete.

Jersey City: The Sixth Borough

Jersey City has transformed from Newark’s gritty little brother into something approaching Brooklyn-across-the-Hudson. The waterfront’s glass towers house Wall Street workers who reverse-commute to Manhattan. Historic neighborhoods like Paulus Hook blend Federal-era architecture with trendy restaurants. The city’s diversity (no ethnic group comprises a majority) creates a genuinely cosmopolitan atmosphere.

But Jersey City’s success brings new challenges. Long-time residents, many of them immigrants who found affordable housing here when nowhere else would have them, face displacement as gentrification accelerates. The city struggles to maintain its character while accommodating growth. The tension between old and new Jersey City plays out block by block, sometimes peacefully, sometimes not.

The Shore Towns

The Jersey Shore encompasses dozens of distinct communities, each with its own character and clientele. Spring Lake, with its non-commercial boardwalk and Irish-American heritage, maintains an understated elegance. Point Pleasant Beach offers middle-class family fun. Seaside Heights embraces its party reputation. Long Beach Island attracts a quieter, wealthier crowd.

Victorian houses in Cape May, NJ

Atlantic City deserves special mention as a cautionary tale of putting all eggs in one basket. The city bet everything on casino gambling, neglecting other development. When competition from Pennsylvania and New York casinos arrived, Atlantic City had no fallback. Today it struggles to reinvent itself yet again, its boardwalk empire reduced to a handful of struggling casinos and persistent poverty just blocks from the beach.

The Suburban Archipelago

Between the cities lies New Jersey’s true heart: the suburbs. From the wealth of the Morristown area to the middle-class subdivisions of Edison, from the horse country of Hunterdon County to the retirement communities of Ocean County, suburban New Jersey defines American suburban living: for better and worse.

These communities, built around cars and single-family homes, face challenges as demographics shift. Millennials seek walkable downtowns. Empty nesters downsize. Immigrants bring new energy but also new needs. Towns that adapt by creating downtown apartments, improving mass transit, embracing diversity thrive. Those that resist change risk stagnation.

Arts, Literature & Creative Heritage

The New Jersey Sound

New Jersey’s contribution to American music cannot be overstated. Bruce Springsteen’s portrait of working-class life defined rock’s social consciousness. The Fugees brought Jersey hip-hop to the world. Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons created the falsetto-driven “Jersey Sound.” Count Basie from Red Bank revolutionized jazz. Whitney Houston from Newark became “The Voice.”

The state’s music reflects its character: unpretentious, hardworking, with an edge of defiance. Jersey artists don’t apologize for where they’re from; they celebrate it. Springsteen could have moved to New York or Los Angeles decades ago but remains in Rumson, drawing inspiration from the boardwalks and back roads he’s known all his life.

Literary Jersey

Philip Roth made Newark’s Weequahic neighborhood as literarily significant as Joyce’s Dublin. His unflinching portraits of Jewish-American life in “Goodbye, Columbus” and the Zuckerman novels captured the aspirations and anxieties of postwar suburbanization. Junot Díaz brought the Dominican experience in New Brunswick and Perth Amboy to international attention. Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe novels dissect suburban anomie with surgical precision.

The state’s literary tradition tends toward realism, even when it ventures into genre territory. Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum mysteries work because they nail the texture of working-class Trenton life. Even when Hollywood comes calling (as with “The Sopranos” or “Boardwalk Empire”) the best Jersey stories maintain their sense of place.

The Art of Architecture

New Jersey’s architecture tells the story of American development. Cape May preserves the largest collection of Victorian architecture in the country. Princeton University showcases Gothic Revival alongside modern masters. The Delaware and Raritan Canal’s industrial architecture speaks to the early industrial age. Mid-century modern houses dot the suburbs, while McMansions represent the excess of the recent past.

The state has also produced significant architects. Michael Graves, based in Princeton, helped define postmodernism. The partnership of Venturi and Scott Brown revolutionized architectural thinking from their Philadelphia-area practice that included many Jersey projects. Even the much-maligned suburban strip mall, perfected in New Jersey, represents a form of vernacular architecture that shapes daily life for millions.

Food Culture & Regional Cuisine

The Holy Trinity: Pizza, Bagels, and Diners

New Jersey’s food culture rests on three pillars, each reflecting the state’s immigrant heritage and unpretentious character. The pizza (thin crust, slightly charred, often sold by the slice) rivals New York’s best. The secret lies in the water, locals insist, though the real answer involves generations of Italian-American pizzaiolos perfecting their craft.

Bagels in New Jersey achieve a perfect balance of crusty exterior and chewy interior. The state’s Jewish communities, particularly in Bergen and Essex counties, support bagel shops that would thrive on the Lower East Side. But here they share strip malls with Korean barbecue and Indian chaat shops, creating a democratic mixing of cultures.

The diner, as mentioned earlier, serves as Jersey’s common ground. The typical diner menu: a phonebook-thick testament to American excess, offers Greek specialties next to Jewish comfort food next to Italian-American classics. This culinary promiscuity reflects the state’s cultural mixing. Where else can you order moussaka, matzo ball soup, and chicken parmigiana from the same kitchen at 3 AM?

The Pork Roll Divide

No food item divides New Jersey quite like the breakfast meat known as Taylor ham in the north and pork roll in the south. This processed pork product, created in Trenton in 1856, tastes like a cross between Canadian bacon and bologna. Served on a hard roll with egg and cheese, it’s the state’s unofficial breakfast sandwich.

The naming controversy reflects deeper regional divisions. North Jersey urbanites call it Taylor ham after the original manufacturer. South Jersey residents, with their Philadelphia influence and agricultural roots, insist on the generic “pork roll.” Central Jersey remains diplomatically neutral, using both terms. The debate, conducted with surprising passion, serves as a proxy for larger questions about state identity.

The Tomato State

New Jersey tomatoes deserve their reputation. The combination of sandy soil, hot summers, and proximity to markets created ideal conditions for tomato cultivation. The beefsteak tomatoes from South Jersey achieve a perfect balance of acidity and sweetness. During peak season, farmstands can barely keep them in stock.

The tomato’s centrality to Jersey cuisine goes beyond fresh consumption. The state’s Italian-American population made tomato sauce as essential as running water. Every family has its recipe, guarded with national security-level secrecy. The “gravy” versus “sauce” debate (another North-South divide) generates nearly as much heat as the Taylor ham controversy.

Ethnic Enclaves and Evolution

New Jersey’s stunning ethnic diversity creates food scenes that rival any major city. Edison’s Little India offers dosas and chaats that transport you to Mumbai. Fort Lee’s Korean restaurants serve bulgogi and soon tofu to rival Seoul’s best. Newark’s Ironbound district maintains Portuguese traditions while Brazilian and Ecuadorian influences grow.

These aren’t museum-piece ethnic neighborhoods frozen in time. They’re dynamic, evolving communities where tradition meets innovation. Second-generation Korean-Americans open French-Korean fusion restaurants. Indian-American chefs incorporate Jersey produce into regional specialties. Portuguese bakeries add Brazilian brigadeiros to their pastry cases. This cultural mixing creates a cuisine uniquely Jersey: rooted in tradition but open to change.

Route 1: The State’s Eastern Thread

The Original Highway

Before the interstates homogenized American travel, Route 1 served as the Main Street of the Eastern Seaboard. In New Jersey, it enters from Pennsylvania at Trenton, winds northeast through the heart of the state, and exits into New York City via the George Washington Bridge. This 66-mile stretch tells the story of New Jersey’s evolution from colonial crossroads to modern corridor.

Route 1 predates the automobile. Its path follows colonial post roads and Native American trails, upgraded and paved but essentially unchanged in purpose, moving people and goods between Philadelphia and New York. Today it serves commuters and truckers rather than stagecoaches, but the fundamental geography remains.

Share your New Jersey route 1 memory

Do you have a story you would like to share? We want to hear it!

Create a View to tell a unique story about a specific place

Want to see what others wrote about New Jersey?

Our Travel map has over 1400 posts from users like you

We have 2 types of content at Route1views:

- View: A unique experience at a single location

- Trip: A collection of experiences at different places, connected through a ‘road trip’

- Most first-time posters choose to make a View

A note about Route 1 Views

We are a user-driven social media site for celebrating and sharing stories along historic Route 1 USA. Using our platform is FREE forever and we don’t play any tricks. We don’t share your data or spam you with emails. We are all about sharing!

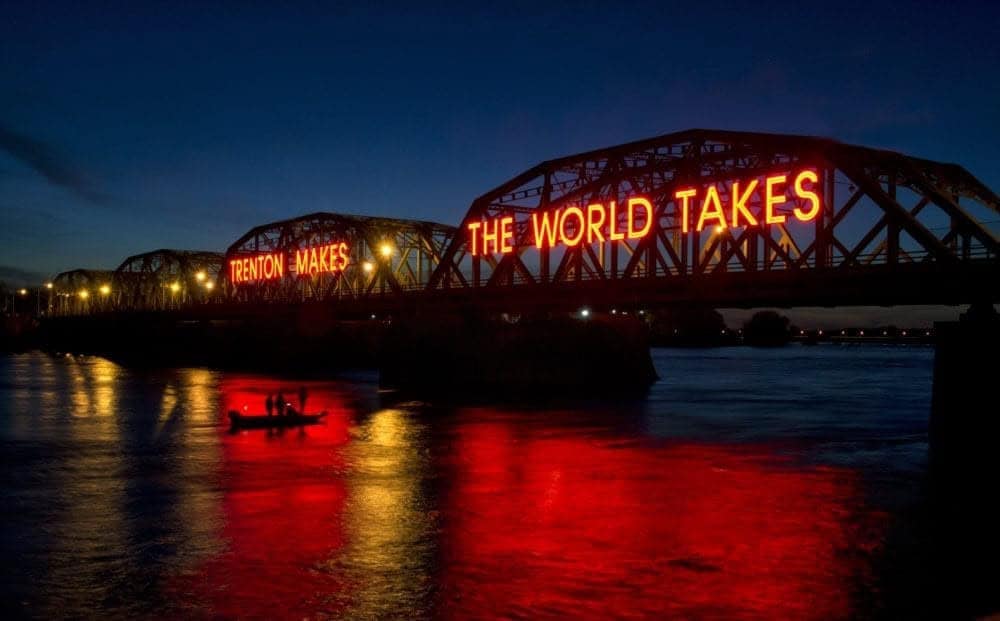

Trenton to New Brunswick

The southern section of Route 1 begins in Trenton, where it crosses the Delaware River on a bridge proclaiming “Trenton Makes, The World Takes” is a boast from the city’s industrial heyday that now reads more like an epitaph. The route passes the golden dome of the State House before plunging into strips of aging shopping centers and car dealerships.

Through Lawrence and Princeton, Route 1 becomes a case study in New Jersey’s economic transformation. Corporate campuses line the highway. Bristol-Myers Squibb, McGraw-Hill, Educational Testing Service. These manicured grounds, invisible from the road behind berms and trees, represent the new economy built atop farmland. Princeton University’s presence looms large here, though the campus sits a mile west, maintaining its bucolic separation from commercial reality.

North of Princeton, Route 1 enters the gravitational pull of New Brunswick. Here it intersects with Route 18, creating a tangle of jughandles and overpasses that epitomizes Jersey traffic engineering. New Brunswick itself, home to Rutgers University and Johnson & Johnson’s headquarters, shows both the promise and peril of urban redevelopment with a revitalized downtown surrounded by neighborhoods still waiting for revival.

The Central Corridor

Between New Brunswick and Newark, Route 1 reveals New Jersey’s suburban soul. Through Edison, Woodbridge, and Linden, the highway passes endless strips of commerce, shopping centers, office parks, chain restaurants, car dealerships. This is the landscape that inspired the shopping mall, where the American dream took concrete form in the postwar boom.

Yet look closer and you see evolution. The old strip malls now house Korean churches, Indian grocery stores, Hispanic botanicas. The demographics have shifted dramatically: Edison’s Little India, Woodbridge’s growing Hispanic population, the Portuguese and Brazilian communities of nearby Perth Amboy. Route 1 serves as Main Street for new Americans, just as it did for previous waves of immigrants.

The Urban Gauntlet

Approaching Newark, Route 1 becomes the Pulaski Skyway, an engineering marvel when it opened in 1932 and a white-knuckle experience today. The narrow lanes and lack of shoulders test even experienced Jersey drivers. The skyway offers spectacular views of the Manhattan skyline while soaring over the Meadowlands (former wetlands turned industrial wasteland turned sports complex turned American Dream mall).

Through Newark and Jersey City, Route 1 takes various forms sometimes elevated, sometimes at grade, always congested. This stretch showcases urban New Jersey’s complexity: Newark Airport’s international connections, Port Newark’s massive container operations, the Ironbound’s vibrant Portuguese community, Jersey City’s gleaming waterfront towers. It’s globalization made concrete, world trade flowing through local streets.

Stories from the Road

Every longtime Jersey resident has Route 1 stories. The diners that serve as landmarks such as the Skylark in Edison, the Delta in New Brunswick. The jughandles that confuse out-of-staters. The shortcuts locals know to avoid the perpetual construction. The evolution of the roadside: from Howard Johnson’s to strip malls to big-box stores to Amazon warehouses.

Route 1 embodies New Jersey’s essential character: practical, unpretentious, constantly adapting. It’s not scenic like California’s Pacific Coast Highway or historic like Boston’s Freedom Trail. It’s a working road for a working state, beautiful in its utility if not its aesthetics. To drive Route 1 is to understand New Jersey; not the postcard version, but the real thing.

Hidden Gems & Local Secrets

The Pine Barrens’ Secret Sites

Beyond the well-known Batsto Village and Wharton State Forest, the Pine Barrens hide wonders known mainly to locals. The pygmy pines near Warren Grove create an otherworldly landscape where mature trees stand just four feet tall. Carranza Memorial, deep in the woods, marks where Mexican aviator Emilio Carranza crashed in 1928, still honored with annual ceremonies by both American and Mexican officials.

The abandoned town of Ong’s Hat exists more in legend than reality, but the stories (involving interdimensional travel and rogue scientists) have made it a pilgrimage site for conspiracy theorists. More tangible are the dozens of forgotten iron furnace ruins scattered throughout the Pines, remnants of the colonial-era bog iron industry that once made Jersey cannon for the Revolution.

North Jersey’s Hidden Wilderness

Most people don’t associate New Jersey with wilderness, but the Highlands region offers genuine backcountry experiences. The Appalachian Trail crosses 72 miles of the state, including Sunfish Pond, a glacial lake that offers alpine views without the alpine altitude. High Point State Park, at 1,803 feet, provides views of three states on clear days.

Lesser-known gems include Tillman Ravine, where a boardwalk leads through a hemlock gorge that feels more like Oregon than New Jersey. The Great Falls of Paterson, America’s second-largest waterfall east of the Mississippi, powered the nation’s first planned industrial city yet remains unknown to many state residents.

Secret Beaches and Forgotten Shores

While summer crowds jam the famous beaches, insiders know the hidden spots. Cape Henlopen’s walking trails lead to pristine beaches accessible only by foot. The Sedge Islands in Barnegat Bay offer a wilderness experience minutes from the developed shore. Bowers Beach, technically in Delaware but closer to many South Jersey residents, provides bay beaches without boardwalk crowds.

In the off-season, even popular beaches transform. October in Cape May offers perfect weather without summer prices. Winter storm watching from Long Beach Island can be spectacular. Spring at Sandy Hook brings migrating birds and horseshoe crab spawning; natural spectacles that predate human development.

Urban Oases

New Jersey’s cities hide surprising green spaces. Newark’s Branch Brook Park contains more cherry trees than Washington, D.C., creating spectacular spring displays that locals enjoy without tourist crowds. Jersey City’s Liberty State Park offers Manhattan views that rival the Statue of Liberty’s. Camden’s waterfront, long industrial, now features parks and the adventure aquarium.

Cherry blossoms in Branch Brook Park, Newark

Smaller urban gems abound. Paterson’s Great Falls finally received National Historical Park designation in 2009, protecting an industrial landscape as significant as any battlefield. Trenton’s Grounds for Sculpture turns a former state fairground into a 42-acre sculpture park. New Brunswick’s Hidden Grounds Coffee, tucked in a basement, serves as an unofficial Rutgers salon where professors and students debate into the night.

The Underground Railroad’s Jersey Routes

New Jersey’s position between slave states and freedom made it crucial to the Underground Railroad. The Peter Mott House in Lawnside served as a station, now preserved as a museum. The Mount Zion AME Church in Woolwich Township hid escapees in its unusual double walls. These sites, often unmarked and known mainly to local historians, tell stories of courage that official histories sometimes overlook.

Modern Challenges & Future Outlook

The Climate Reckoning

Climate change poses existential challenges to a state where millions live near sea level. In the past 20 years, New Jersey went from having more than 20 percent of U.S. pharma manufacturing jobs to less than 10 percent.

Hurricane Sandy in 2012 offered a preview: $37 billion in damage, entire communities destroyed, infrastructure overwhelmed. The rebuilding continues, but harder questions loom: Should barrier island communities rebuild in place? Can shore towns survive rising seas? How do you retreat from the coast when coastal property drives municipal tax bases?

The state has responded with some of the nation’s most aggressive climate policies. Offshore wind farms are planned along the coast. Solar panels sprout on warehouse roofs and former landfills. Yet implementation faces resistance from those who fear economic impacts or aesthetic changes. The tension between environmental necessity and economic reality plays out in planning board meetings and statehouse hearings.

The Inequality Challenge

New Jersey contains some of America’s wealthiest communities and some of its poorest, often separated by just a few miles. The state’s reliance on property taxes to fund schools creates a vicious cycle: wealthy towns have excellent schools that attract more wealthy residents, while poor communities struggle with inadequate funding despite higher tax rates.

The state Supreme Court’s Abbott decisions mandated equal funding for poor districts, but implementation remains contentious. Charter schools offer alternatives but drain resources from traditional public schools. The fundamental question, how to provide equal opportunity in an unequal state, remains unresolved.

The Identity Crisis

As New Jersey evolves, it grapples with fundamental questions of identity. Is it a suburb of New York and Philadelphia or a state with its own character? Should it embrace development to remain economically competitive or preserve remaining open space? How does it balance the needs of longtime residents with those of new immigrants?

The average New Jersey farmer is over 60 years old, raising concerns about the future of agriculture. Meanwhile, Like many states, New Jersey farms are primarily owned and operated by families or individuals, with 7,849 family farms as of 2022, or about 78.5% of all farms in the state.

The pharmaceutical industry, once the state’s crown jewel, continues its transformation: “Essentially, every time there’s a merger or one company acquires another company, there’s a reduction in force, and there’s been furious mergers and acquisitions in the pharma industry, particularly over the past 10 years,” says James Hughes, dean of the school of public policy at Rutgers.

The Infrastructure Imperative

New Jersey’s infrastructure, built for the 20th century, strains under 21st-century demands. The Portal Bridge, a chokepoint for Northeast rail travel, opens for boats more readily than it carries trains. Water systems in many cities date to the 1800s. The electrical grid struggles with summer demand and storm damage.

The Gateway Tunnel project under the Hudson River represents both the challenge and opportunity. This massive undertaking would double rail capacity between New Jersey and Manhattan, but funding battles have delayed it for years. Without it, the regional economy faces gradual strangulation. With it, New Jersey could capture more benefits from its proximity to New York.

The Suburban Evolution

The postwar suburban model that defined New Jersey faces fundamental challenges. Millennials seek walkable communities, not car-dependent suburbs. Office parks empty as remote work becomes permanent. Shopping malls struggle against e-commerce. The state must reimagine suburbia for a new era.

Some communities show the way forward. Morristown has created a vibrant downtown mixing apartments, offices, and entertainment. Hoboken became a model for urban revival. Even struggling cities like New Brunswick and Asbury Park have found new life through arts districts and transit-oriented development. The question is whether these examples can scale across a state built on a different model.

Conclusion: The Persistent Garden

New Jersey endures because it adapts. The state that transformed from colonial crossroads to industrial powerhouse to suburban prototype now faces another transformation. Its assets remain formidable: location, diversity, education, infrastructure (however aged), and a population that combines provincial pride with cosmopolitan awareness.

The Garden State metaphor, mocked by those who only know the Turnpike’s industrial corridor, actually captures something essential. Gardens require constant tending. They go through seasons. They can appear dead in winter yet bloom again in spring. They mix the cultivated and the wild, the planned and the spontaneous.

New Jersey in the 21st century remains what it’s always been: a place of transitions, a threshold between places and ideas. It’s where immigrants become Americans, where cities meet suburbs meet wilderness, where the past persists alongside the future. Understanding New Jersey means accepting these contradictions, embracing the mess alongside the beauty.

For those who know where to look beyond the highways and stereotypes, New Jersey reveals itself as one of America’s most complex and compelling states. It’s not always pretty. It’s rarely simple. But for those who call it home, and for those willing to explore beyond the surface, New Jersey offers rewards that no highway sign or reality show can capture. The garden grows on, stubborn and resilient, bearing fruit for those who tend it.