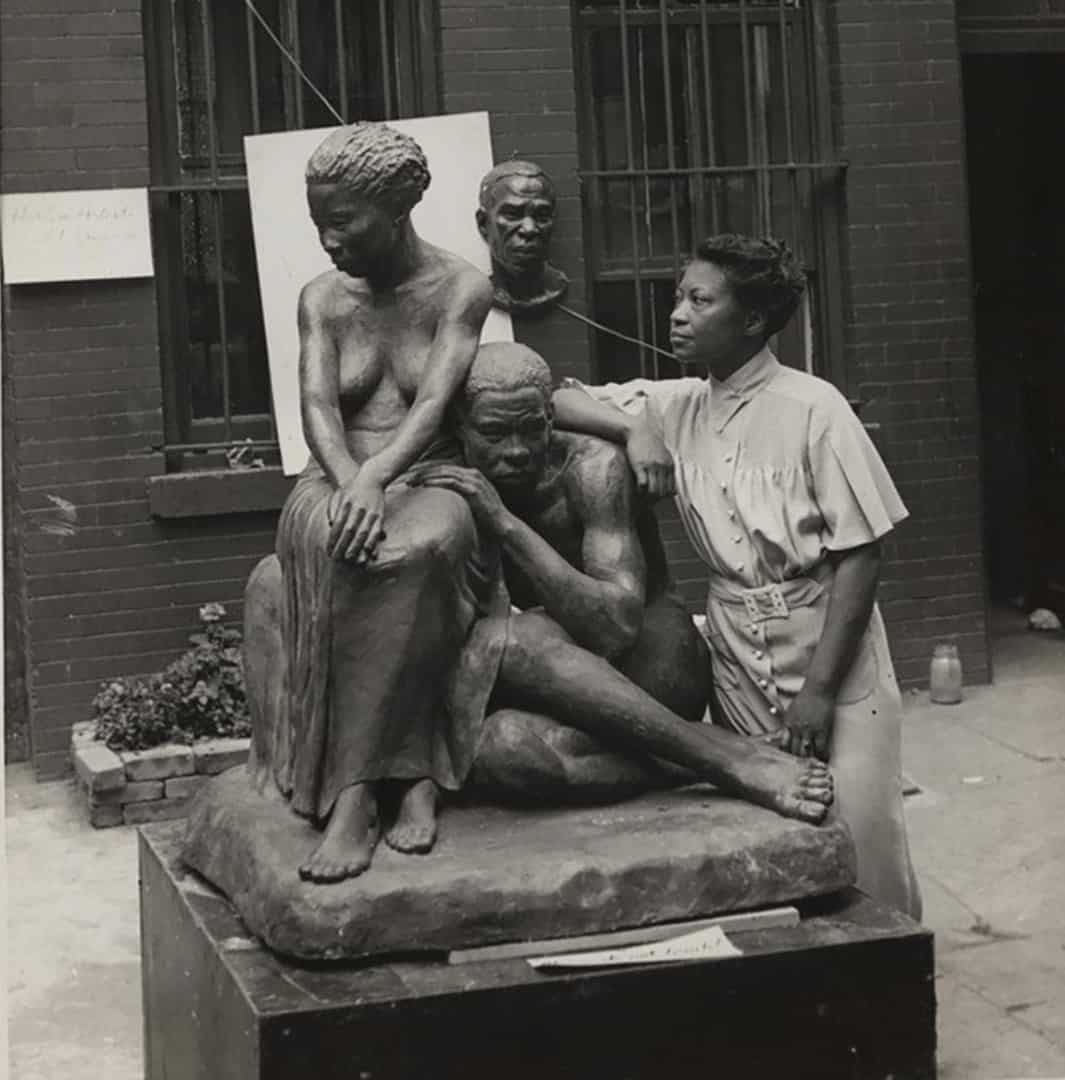

Augusta Savage the Harlem Renaissance Sculptor

Augusta Savage was a sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance who repeatedly broke the mold on what it meant to be a woman, an artist, and an African American in the pre-Civil Rights era. From pushing back on racism in the press, to successfully creating masterpieces from alternative materials, to being the first African American woman to open her own gallery, Savage’s narrative illustrates a woman who understood obstacles as temporary, artistry as a vocation, and her legacy as the gifts she shared with her students. Savage’s Early Life in Florida Augusta Savage was born off Route 1 in Green Cove Springs, Florida, on February 29th, 1982. She interpreted her Leap Day birthday as a sign of her unique destiny, once commenting, “I was a Leap Year baby, and it seems to me I have been leaping ever since.” Green Cove was a brick-making town, abundant with the red clay that served as material for Savage’s earliest sculptures. Savage’s father, however, opposed her creativity on religious principles. He would beat her four to five times a week, but Savage remained undeterred. By the time she reached high school, she not only enrolled in a clay modeling class, but wound up teaching it because of her exceptional talent. Savage lived in West Palm Beach after graduating, accumulating awards for her work while trying to build a family. She married and had a daughter with her first husband, who passed away after a few years. Savage then wed James Savage, whom she went on to divorce (although she kept his name). After discovering that she couldn’t make a name for herself sculpting busts of well-known city figures in Jacksonville, Florida, Savage placed her daughter in her parent’s care and moved to New York City. Savage’s Formative Years in HarlemSavage arrived in Harlem with just $4.60 in her pocket. She began cleaning houses while studying at The Cooper Union School of Art. Her talent prompted her instructors to waive several of her program’s courses, resulting in a three-year graduation. Savage continued to sculpt, and in 1923 received a scholarship for a summer art program in Fontainebleau, France. When the French government discovered her race, however, they rescinded the offer. Savage contacted the press with her story: a bold move for an African American woman at the time, which resulted in her making headlines. American sculptor Hermon A. MacNeil, who sat on the selection committee for the program, invited Savage to study with him in attempts to atone for the decision. Instead, Savage began participating and contributing to her artist’s community. She made sculptures out of plaster and painted them over with shoe polish in order to resemble the bronze she couldn’t afford. One such sculpture, named Gamin, is a bust of an African American boy wearing a skeptical expression, soft cap, and wrinkled shirt. The work sent a powerful message: that the ordinary black child was a work of art. Savage also sculpted busts of more prominent African Americans, like W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey. After six years of sculpting and garnering support for her work, Savage finally gained admission to study in France. She studied there for three years, founding her own art studio and school upon returning to the States in 1932. Savage’s Contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and New York Art Scene Savage’s studio became a cultural touchpoint in the Harlem Renaissance. Over the span of the next decade, teaching and sculpting became the two dual passions that Savage built her legacy upon. Many of her students become famous, and Savage herself said that those she taught were the “monument” she would be remembered by. During this time, she also trailblazed numerous milestones: Savage became the first African-American member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors; she opened up the first art gallery owned by an African American woman, and was appointed the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center. Her work, meanwhile, centered upon depicting African Americans both well known and forgotten. A statue of the boxer Jack Johnson, for instance, became famous for connoting the fighting spirit necessary for progressing racial justice. But Savage’s most famous contribution arrived in 1937, when the New York World Fair commissioned her to create a sculpture depicting the musical contributions of African Americans. Savage designed a 16 foot tall painted plaster sculpture named Lift Every Voice and Sing: a title inspired by a James Wheldon poem of the same name. The sculpture depicted a harp, where 12 African American singers formed the strings, and the hand of God served as the soundboard. After changing the name to The Harp, World Fair Officials debuted the sculpture at the 1939 World Fair. Over five million people viewed the masterpiece, and it became the event’s most photographed object. However, bulldozers destroyed The Harp alongside the rest of the fair’s artwork at the event’s conclusion. Symbolically, this action marked the end of Savage’s career as well. She lost her position at the Harlem Community Art Center, and the looming World War stripped away the funds necessary for other endeavors. In 1945, depressed over her losses, Savage rekindled relations with her daughter and her family and moved to upstate New York where she passed away in 1962. Like The Harp, much of Savage’s work was destroyed or lost. Her contributions to the Harlem Renaissance lived primarily in the work of her students until the millennium, when a retrospective by the New York Historical Society, alongside some very belated press, strove to revive her legacy.

Elisia Guerena NY New York Oct 12, 2020 Visual Arts