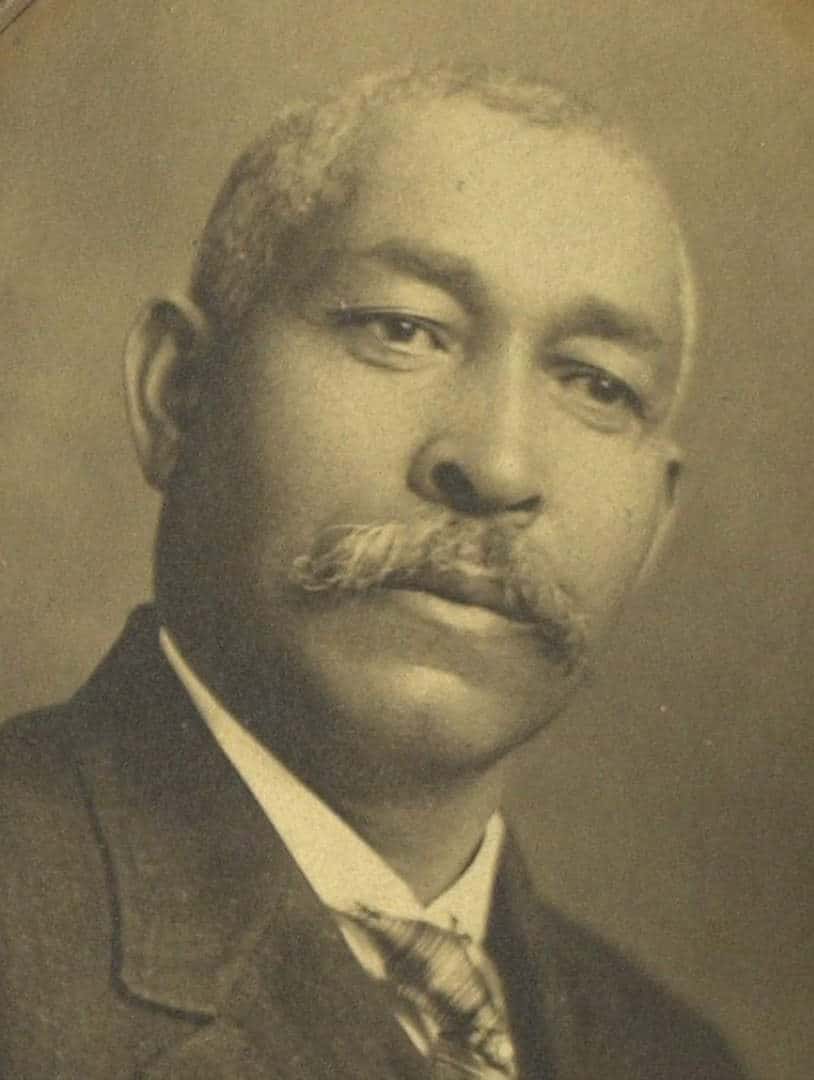

Dr. Manassa T. Pope: Builder of Community, Health, and Hope

Three blocks to the East of Route 1 in Raleigh, North Carolina stands the Pope House: a two-story brick structure with a modest clapboard addition jutting out the house’s back end. With modern high rises surrounding it, the house stands apart from the rest, making it just as remarkable now as 100+ years ago when built by Dr. Manassa Thomas Pope. Pope was a prominent Raleigh physician who worked with the African American community to promote their health, rights, and pride in their cultural heritage. He used every outlet available to him for this mission, including his career, political involvement, and the home for which he’s now best remembered. Pope’s Upbringing, Education and War Involvement Pope was born East of Route 1 near Rich Square, North Carolina, in 1858. His parents were free Quaker African Americans, and while little is known about his mother, his father was a well-educated land-owner of mixed racial heritage. Pope moved to Raleigh in 1874 to study at Shaw University. Founded in 1865, this historically Black educational institution was a triumph for African Americans at the time. It acted as the city’s Black cultural center, and offered the nation’s first medical school for Blacks, as well as some community hospital care. Pope graduated medical school in 1886, as a member of the college’s first-ever graduating class. From there, he went on to become the state’s first medically-licensed African American doctor. Within a few years of earning his medical degree and license, Pope had married and moved to Charlotte, North Carolina (with a brief interlude in Henderson, NC), to practice medicine. During that time, he worked vigorously as a businessman to plant seeds in the community, and very well may have seen them come to fruition, had the Spanish American War not caused him to redirect his efforts to forming an all-black volunteer regiment and serving as its first assistant surgeon. The Building of Pope House In 1899—with an honorable discharge under his belt and a growing track record of promoting African American influence and societal presence—Dr. Pope and his wife moved to Raleigh. He immediately started up his practice, while also building his house. Several characteristics of the Pope House stood out that helped establish its significance today. The first is its location. At 511 Wilmington Street, the house faced the backs of homes belonging to upper-class whites one block over. Historians surmise that Pope built his house there in order to take a stand against racial segregation, which often pushed Black residents towards poorer sections of Raleigh. The home’s design choices also speak to Pope’s dedication to overturning racial barriers. He opted for expensive brick over wood as a way of signaling his wealth (and its related social prestige) to those who passed by. The interior of the home boasts handsome wood trim, a stained glass window, and the best amenities available at the time including a kitchen with running water, coal-burning stoves, a telephone, a full bathroom, and a call bell system for hired help. Pope, his wife, and his two daughters were the only ones to ever live in the house. Today, it retains most of the features of its original state, with domestic items preserved alongside the architecture. Visitors can observe the medical instruments Dr. Pope used when treating patients (he worked out of his home, as well as his medical office a few blocks away); a piano, lace dresses worn by his wife and daughters, and even traces of the home’s original wallpaper. Pope’s Activism and Run for Mayor Pope’s house was a symbol of not only his success, but his dedication to proudly standing behind his capabilities and rights as an American citizen: regardless of the reception or outcome. This trend continued when he worked around state laws that aimed to keep Black men from voting. Pope managed to receive his voter registration card in 1902 as one of only seven other Black Raleigh citizens to do so. When the government started enlisting African Americans to fight in World War I, it brought the issue of African American rights—or their lack thereof—to the forefront. Pope contributed to this movement by helping establish the Twentieth Century Voters’ Club: a group that encouraged African Americans to stand up for their voting rights. Then in 1919, Pope went on to engage in his most high-profile political act. He ran for mayor, at a time when African Americans who challenged the status quo or dared distinguish themselves in any way ran the risk of inciting white supremacists. Pope received 126 ballots out of 2,550. Pope motives weren’t rooted in an expectation of victory, but as a symbol of a Black man’s potential regardless of current prejudices. That being said, his very act of running was a victory, regardless of the outcome. Pope’s two daughters went on to become well-respected educators, who returned to their childhood home after their father died in 1934. The city of Raleigh claimed the home in 2005, five years after the passing of Pope’s last-surviving daughter. It’s now available for tours, and Raleigh has hosted exhibitions displaying the artifacts that tell the story of the doctor’s legacy.

Elisia Guerena NC Raleigh Dec 23, 2020 Architecture