Jack Johnson the Boxer: His Final Victory

Route 1 runs through the small town of Franklinton, North Carolina. Along one of its many twists and turns stands a light pole where once a year, a wreath appears. It’s the site’s only tribute to Jack Johnson, one of history’s most legendary heavyweight boxers, who fatally crashed his Lincoln Zephyr into that pole on June 10, 1946. Driving at an estimated 80 miles an hour, Johnson’s speed was fueled by rage: he was racing away from a restaurant that refused him service because he was black. The circumstances of Johnson’s death mirror many of those he faced in life. Johnson alternatively fled racism and used it to fuel his rise to unprecedented heights as the turn-of-the-century’s most prolific and controversial athlete.

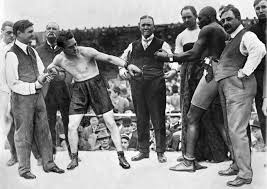

Jack Johnson’s Rise as a Boxing Champion

Jack Johnson was born in 1878, the son of former slaves in Galveston, Texas. Johnson’s boxing career began unofficially as a teenager, when he would participate in “battles royal” matches that entailed white spectators tossing money at the winner of a boxing match between African Americans. Johnson continued fighting in Texas until 1897, when the state—which considered boxing a criminal sport—arrested and jailed him. After that, he moved to New York, setting his sights on becoming the world’s first African American heavyweight boxing champion. For context: boxing as a sport was still developing at the turn of the century. The rules as they stand today didn’t exist, and the media was responsible for determining the winner of matches that didn’t end in knockouts. This shifting terrain, coupled with the heavy racism of those times, ensured that any African American contender would need to work twice as hard to make it—for many people didn’t want to see an African American triumph, especially over a white opponent. Johnson used this opposition as fuel. He fought consistently, steadily garnering wins and public recognition until 1908, when a match won over white champion Tommy Burns placed him as the first African American heavyweight champion of the world. Johnson’s victory placed him as the subject of intense backlash. White fans denied his legitimacy and actively sought another boxer who could displace him from his seat. Johnson, meanwhile, resisted kow-towing. He lived an openly extravagant and public lifestyle. The tension manifested in white fans goading retired heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries to come out of retirement and reclaim the title from Johnson. Jeffries persistently resisted until the $120,000 offered to him if he won convinced him to step up to the match. Despite Johnson’s peak physical prowess and Jeffries’ faded glory, the media heavily favored Jeffries to win the match, and fans called him “The Great White Hope.” Racial tensions surrounding the event became so taut that, in the days leading up to the match, fights broke out among the public and the arena (custom-built for the event in Reno, Nevada) prohibited guns or alcohol. On July 4th, 1910, Johnson and Jeffries met up for “The Fight of the Century.” The overwhelming negative attention aimed at Johnson didn’t sway him. He won the match after 15 rounds, during which Jeffries was taken down twice and finally threw in the towel in order to avoid having a knockout on his record. Johnson won $65,000 for the match and finally settled the score on the legitimacy of his title. Johnson’s undisputed victory resulted in racially-fueled riots across the country. The upset over a fairly won fight proved out what Johnson had undoubtedly been combatting his entire life—that no amount of hard work or undisputed excellence could quell or convince the country of an African American’s right to equality.

Johnson’s Fight or Flight Modes

Despite his stance as the victor, Johnson couldn’t win out every fight, especially those that occurred outside the ring. In 1912, he was arrested while driving his 19-year-old white girlfriend across state lines. Authorities charged him with violating the Mann Act, an anti-prostitution law that prohibited transporting women across state lines for “immoral purposes.” Historians view the case as racially motivated: Johnson’s many relationships with white women broke a serious taboo, and the all-white jury found him guilty. Johnson fled to Europe for several months to avoid incarceration, before returning and serving less than one year of time in prison. Although Johnson lost his title in 1915, he continued to ride the waves of fame through the 1920s and 1930s. He took up speaking engagements across the country while continuing his unapologetic lifestyle that included a love of opera, reading, furs, and cars. On June 10th of 1946, Johnson was driving with his friend Fred Scott to a speaking engagement. While details vary from account to account, the general narrative surrounding Johnson’s death goes like this: Johnson stopped at a diner for lunch. The establishment either refused to serve him or asked him to sit outside. Enraged, Johnson took to his car and began speeding down route 1, through a tightly winding section nicknamed “Cadillac curve” because of the number of cars that careened off course. Just past Evergreen Cemetery, Johnson hit a light pole. Both passengers were ejected from the car; an eyewitness recalled arriving on the scene to hear Johnson say “I’ll be alright.” Although a nearby funeral home had access to an ambulance, they refused to drive him because he was black. Instead, Johnson was transported via hearse to Agnes Hospital—again, chosen because the nearby Rex Hospital refused to see black patients. Some people believe Johnson could have lived if he had access to the right care. His death inspired music, documentaries, and commentary throughout the decades and into the millennium when President Trump pardoned his conviction in 2018 as a “racially motivated injustice.” From beyond the grave, Johnson won his last fight.

Elisia Guerena Oct 20, 2020 Franklinton NC Sports