James Leonard Farmer, Freedom Rider

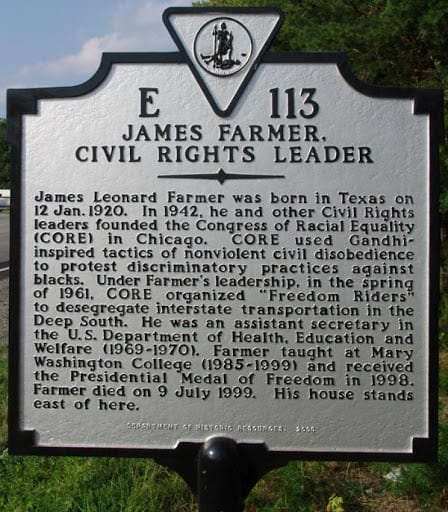

Driving along Route 1 in Virginia and you’ll be sure to notice, as the miles pass, white signs with black text. If you stop long enough to read them, you’ll notice that these signs are historical markers that share abbreviated stories of legendary figures and moments. One such sign in Spotsylvania, Virginia remembers James Leonard Farmer, Jr.: a Civil Rights activist who helped guide the struggle for racial equality in the 1950s and 60s. Farmer instilled his legacy along the Route with both his work and personal life. He not only lived and died close by, but his famous “Freedom Rides”—bus trips that were taken from the North to the deep South in order to desegregate bus lines—rode along Route 1. Whether you’re road-tripping (or daydreaming about it), here is the background on this legendary figure to enrich your journey.

James Farmer’s Early Life

James Farmer, Jr. was born on January 20, 1920 in Marshall Texas. His father, James Farmer Sr., was the son of a slave who went on to become the first black man from Texas to ever earn his doctorate. James Farmer Sr. was a minister, scholar, and a prominent college professor by the time his son was born, while James Farmer Jr.’s mother was also a teacher. With two highly educated parents, James Farmer Jr. was born into a household that valued and fostered a love of learning. His upbringing was so steeped in academia, in fact, that it shielded him at first from the realities of racism and segregation. It wasn’t until an incident in Mississippi when Farmer was three or four that he realized the inherent inequality of the world he lived in.

After finishing high school, Farmer went on to earn degrees from two historically black institutions: Wiley College (located in his hometown), and Howard University in Washington, D.C. During this time, he continued to observe racial injustices and plan larger ways to shift their narrative. While Farmer’s contributions to the Civil Rights movement are numerous, his most celebrated ones are the formation of CORE and his Freedom Rides.

Farmer’s Involvement in CORE

One of Farmer’s greatest contributions is the role he played in founding CORE, which stands for Congress of Racial Equality. Farmer’s interest in a formalized activist group took root in Chicago in 1942, when he and a friend entered a coffee shop. The counterman waited to serve them in a near-empty restaurant, tried to charge them $1 for nickel doughnuts, and finally threw their money on the floor before telling them to leave. Farmer and his friend staged a sit-in at the establishment, marking the first successful protest of their future organization. Within three years of its formation, CORE had 70 chapters nationwide with over 60,000 members.

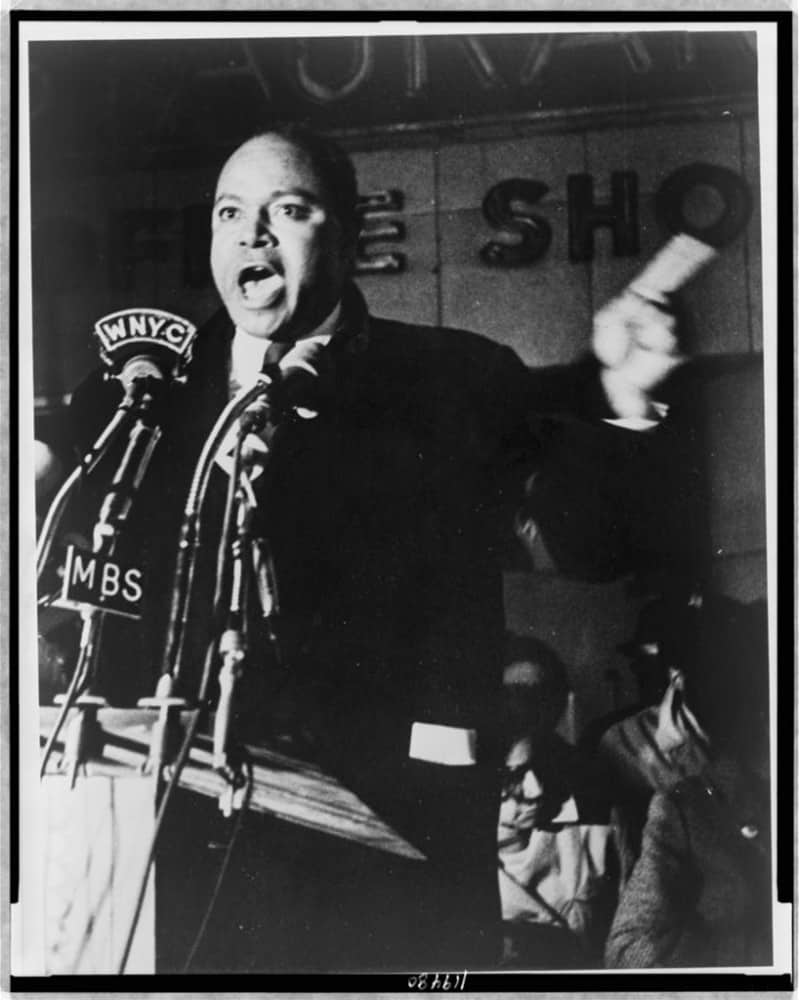

Farmer stood as the direct-action leader of the organization, which was involved with several pivotal Civil Rights moments. Students who participated in sit-ins that started in Greensboro, North Carolina turned to CORE for support. When three CORE members—two black and one white—were murdered by the KKK after promoting Black voter registration and investigating a church burning, their violent deaths stood as tragic emblems of the price of progress. Farmer’s most legendary contribution was as an organizer and participant of “Freedom Rides”: bus trips that went from the North to the South in order to desegregate interstate transportation. Although the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregated seating on these trips unconstitutional in 1946, the South largely ignored that law, while those who challenged the status quo risked losing their lives. In 1961, Farmer and his colleagues set out to change that, by organizing four different trips that brought Black and white activists together on bus rides throughout the U.S. When the riders stopped in a segregated town, Black people would use white restrooms, and vice versa: a peaceful form of protest that adhered to the doctrine of nonviolence Farmer had adopted from Mahatma Ghandi.

Farmer participated in a Freedom Ride that began in Washington, D.C. and ended in Birmingham, Alabama. This group of activists slept over in Petersburg, Virginia, after talking at Bethany Baptist Church; they then proceeded to Augusta, Georgia, where they met with students to discuss their work. The further into the South that the Riders went, the higher the danger: some riders were assaulted in Virginia and the Carolinas, and Farmer knew that his chances of getting injured or worse ran high. According to the NYTimes, Farmer completed his journey in peace “because of a deal worked out between Attorney General Kennedy and James O. Eastland, the segregationist Senator from Mississippi. But Mr. Farmer was arrested in Jackson for disturbing the peace and spent 40 days in Mississippi jails.” Still, he considered it a success: “Bobby Kennedy had the Interstate Commerce Commission issue an order, with teeth in it, that he could enforce, banning segregation in interstate travel,” he told the NYTimes, adding: “That was my proudest achievement.”

Farmer continued working to better the country far after the Freedom Rides. He was Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, taught at Lincoln University, penned two books, received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and continued contributing to the conversation on Civil Rights before passing away in Fredericksburg, Virginia from long-standing health complications. Today, The James Farmer Multicultural Center in the University of Mary Washington, which is only a quarter-mile off Route 1 in Fredericksburg, stands as just one tribute to a man whose contributions are inestimable in impact and legacy.

Elisia Guerena VA Fredericksburg Dec 10, 2020 People

Dec 10, 2020