Pocahontas Island: A Diamond in the Rough

At the north end of Petersburg, bordered by the Appomattox River sits Pocahontas Island: a 70-acre area of land that marks one of the nation’s earliest African American communities. Nowadays its inhabitants number less than 100. In the 1800s, however, it was a place where hundreds of Black people and abolitionist whites lived together peacefully, making history as Underground Railroad participants, while creating a sort of “promised land” that provided Black people with the potential to work and live as equals. Richard Stewart, who is the honorary Mayor of Pocahontas Island and opened a Black History Museum there, says that the island “is a mecca of history. It’s not only black history, it’s white history, Native American history—it’s American history.”

The Founding of Pocahontas Island

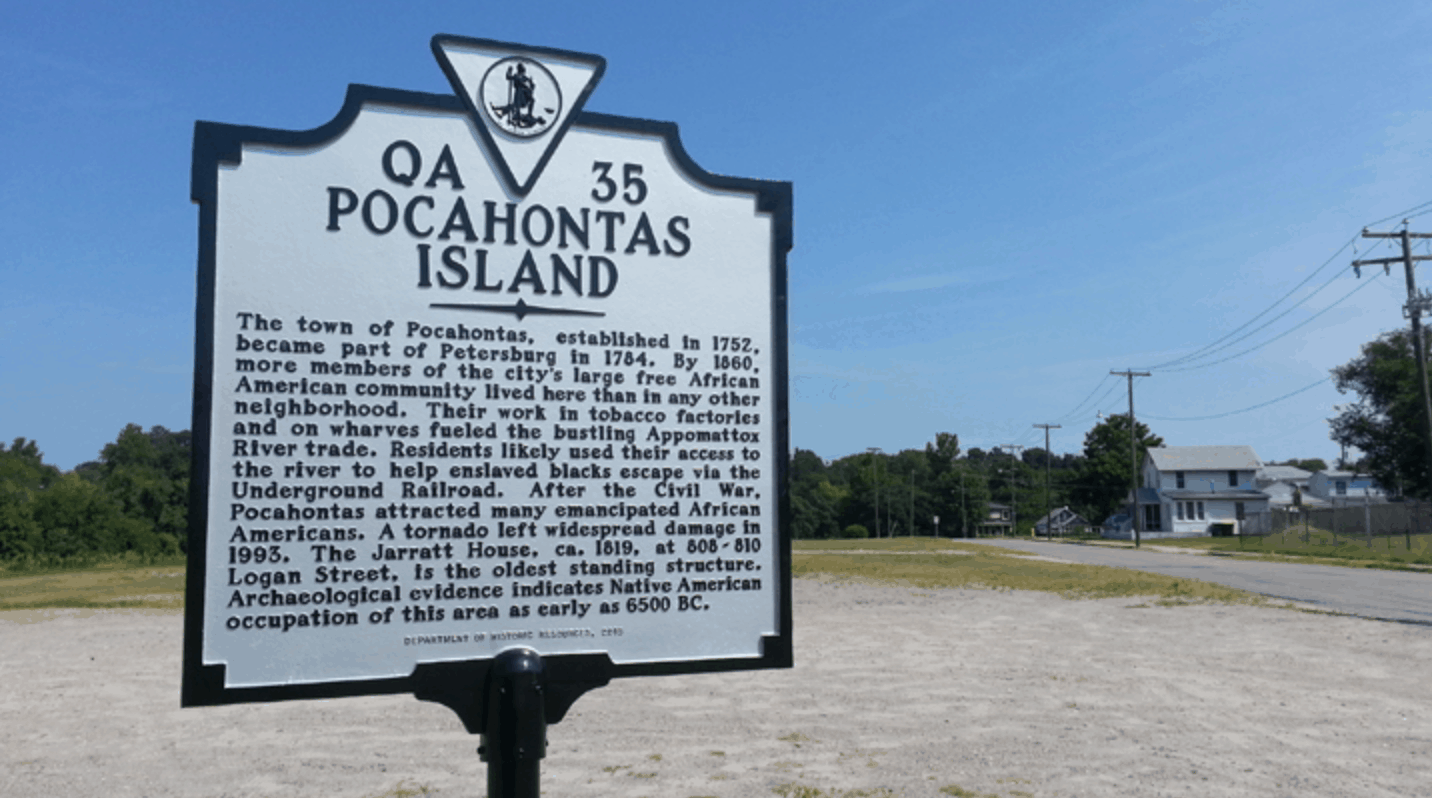

Pocahontas Island was founded in 1732, the same year that enslaved African Americans arrived in the community to work in tobacco warehouses. The area was renamed Pocahontas Island when it became an official town in 1752; even after it merged with Petersburg in 1784 it retained its name. By the late 1700s, the town was home to freed Blacks, who helped build a church with enslaved African Americans from Prince George County.

The Anomaly of Freed Blacks and Their Promise to Others

The island is remarkable for several reasons. The fact that freed African Americans, who had managed to buy their freedom, were able to live there after liberating themselves (before the Civil War) is highly unique in and of itself. Their ability to build community and create a narrative—well before society allowed most African Americans basic human rights—is also exceptional. Take, for example, the area’s history as a major stopping point on the Underground Railroad. The nearby river aided in the escape of enslaved persons from the South. To this day, visitors can observe two homes that aided the escape of enslaved persons from the South; one of the homes even allows you to look in the basement that housed the refugees. Legend has it that the island also hid a participant in Nat Turner’s rebellion, was called home by Liberia’s first elected president, and was the childhood home of the famous enslaved- person-turned-horseman Charles Stewart.

Charles Stewart is, in fact, a distant relative of Richard Stewart, who grew up on the island and now represents the island and its history through a Black History Museum that he founded in 2003. This passion project houses Stewart’s collection of books, historical documents and independent research he’s conducted through conversations with the island’s older generation. Visitors must make an appointment to visit the museum, but when they arrive they receive a personalized tour by Stewart of its various artifacts. These items include slave papers that document the selling of African Americans; whips used to punish enslaved persons and shackles used to bind them; and glass, ceramics, and tools found beneath the floorboards of one of the houses on the Underground Railroad.

Stewart is passionate about the area and its subject matter, as are its other residents. A local resident interviewed by CBS6 News talks about the Jarratt House, which was bought by freed Black man Richard Jarratt in 1820. “To have Black, family-owned real estate in the early 1800s, that’s almost unheard of,” said the interviewee. Jarratt was a boatman who traveled back and forth from Petersburg to Norfolk for his fishing business. His life stood as a sort of promise, a representation of what the approximately 300 other Black persons living on the island sought: freedom to work, live, and own land. It was “phenomenal for a Black to own real estate in 1820,” agreed Stewart in a separate interview. He covers the history of the house: how its plaster contains horsehair which was commonly used as a binder during the early 1800s; how it was donated to the city in the early 1990s, and avoided disaster in 1993 after a tornado hit the town and destroyed many of its buildings. Nowadays, Stewart hopes that the house can be restored and used for community events.

Until then, he does what he can to preserve the Island’s history. Stewart owns the William Walthall House, another historical landmark that was originally owned by a “Black man who had a white mother. He was a twin. She [had] sold him and his brother to a man named Hardy that later died.” After Hardy’s death, Walthall gained his freedom and built the house in 1837, using it to host fugitive slaves. Stewart has rebuilt an outhouse that was part of the original property, as well as painted the house a bright shade of pink: a tribute to its original color.

Pocahontas Island was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006. Despite its immense historical importance as one of the country’s oldest African American communities, the area is easily overlooked, earning it the reputation as a diamond in the rough. Its remaining residents and history enthusiasts hope that more people can learn about its history and appreciate its value. For Stewart, Pocahontas Island is his way of life. “It’s all I got, my folks died here,” he says. “I don’t know how to live in another place. I can sit on my porch and go to sleep. I don’t care what direction I look, it’s part of my family. We’re all kin over here—some way, somehow.”

Elisia Guerena VA Petersburg Dec 10, 2020 Architecture

Dec 10, 2020