The Overseas Railroad’s Almost Forgotten Laborers

One of the most famous sections of Route 1 is along the Overseas Highway: the 113-mile stretch of road that carries automobiles from Florida’s mainland into the Key Islands. The Highway is best known for its engineering prowess and breathtaking views; however, its construction also tells the story of labor exploitation practices in the early 1900s.

Today, at Mile Marker 45 in Pigeon Key, passengers can observe eight standalone structures that stand as a tribute to those practices. They are part of a railroad construction work camp that was built for laborers on “the Overseas Railroad.”

The predecessor to the Overseas Highway, this railroad line was designed by oil tycoon and industrialist Henry Flagler, who relied upon the labor of thousands of immigrants and African American convicts for its completion. Their contributions came at the cost of humane work conditions, reasonable pay, and in some instances, their life.

Henry Flagler’s Florida Fantasy

Henry Flagler first turned his attention towards Florida in 1878, when doctors recommended that his ailing wife visit Jacksonville to help her health. Although the state couldn’t cure his wife (she passed away in 1881), Flagler remained fascinated by Florida, viewing its underdeveloped commerce and rich natural resources as an opportunity for expanded tourism. So after remarrying and honeymooning in St. Augustine, he turned his attention from Standard Oil—the enterprise that had earned him his fortune—and began investing heavily in making Florida more accessible.

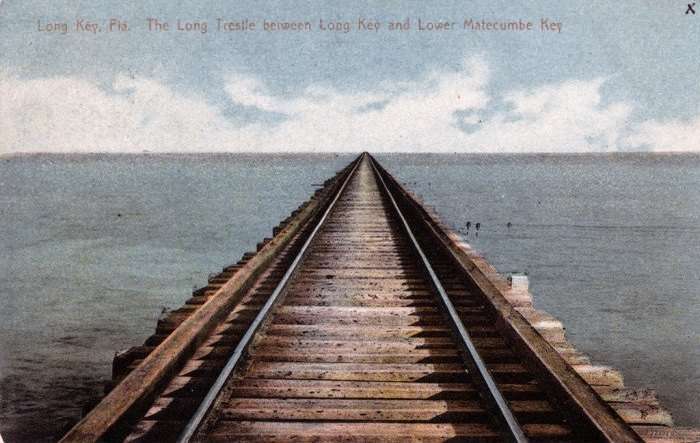

Flagler began this process by building railroads through Florida. By 1896, his railroad line had reached the Biscayne Bay. In 1905, the start of construction on the Panama Canal inspired Flagler to continue building south in his most ambitious initiative yet: to build a railroad straight over the Floridian waters, linking the Key West islands to the mainland.

Constructing the Overseas Railroad

To build the Overseas Railroad, Flagler needed manpower well beyond that contained within state lines. Flagler’s built a labor pool that drew from two sources: African American convicts and New York immigrants.

At the time, state penitentiaries could lease out convicts to projects like those run by Flagler. As the Washington Post explains, the exchange was mutually beneficial to both the penitentiaries and the industrialists.

It gave the state both revenue and a tool “to intimidate and control black citizens.” Private businesses, meanwhile, received “vulnerable laborers who could be worked beyond human endurance and brutalized at whim.” in other words the system not only provided Flagler with cheap labor: the threat of punishment, by either the penal system or the labor camp officials, ensured that workers worked beyond their limits while staying in line.

Convict labor alone couldn’t build the railroad. To make up for the deficit, Flagler ran an aggressive recruiting campaign among New York immigrants. He ran job advertisements that called for 1,000 laborers, listing generous wage scale prices and the opportunity for promotion in exchange for bringing other workers on board. Over time, the lure of sunshine and money caused an estimated 15,000-20,000 European immigrants of Italian, Slavic, Greek, and German descent to take the bait and go South.

Upon arriving at the work site, however, these immigrants found the reality to be far different than that depicted by the advertisements. Florida was not just sunny—it was hot, humid, and insect-ridden, with no protection between workers and the elements.

Even though the advertisements had listed pay grades that increased with skill level, every man who arrived on site was tasked with the lowest-paying job of clearing away trees and plants to make room for the railroad. Workers also found that the recruiter’s offer of free room and board was false.

Instead, they had to pay a weekly fee to share flimsy tents and small portions of substandard food. Many men, upon encountering these conditions, tried to leave. Once they reached Miami, however, they were told that their pay was being withheld to cover the cost of their transportation, and would only be released after they had worked for six months. (The convicts, meanwhile, worked for free.)

Muckraking journalists eventually caught on to the poor labor conditions, calling out the practices as “Industrialist Slavery.” Flagler retaliated by running stories in the newspaper he owned, the Union. This front-page story contradicted their reports and offered a version of the story that included well-taken care of laborers, including the claim that “the rough work of clearing is being done entirely by Negroes, they being accustomed to the use of an axe.”

Eventually, the Overseas Railroad project built dormitories and houseboats for the workers. Unfortunately, these new living arrangements couldn’t protect workers from a hurricane in 1906 that claimed the lives of approximately 200 men on a houseboat torn asunder by the winds.

The Overseas Railroad was completed in January of 1912. Just over a year later, Flagler fell down a flight of stairs and died. In 1935, a powerful hurricane that was later known as “The Storm of the Century” hit the Florida Keys and demolished most of the railroad, which by that point had already gone bankrupt.

The state of Florida bought back the remains and turned it into the Overseas Highway as it stands today: an engineering triumph and, at Mile Marker 45 at least, a reminder of the unjust labor practices that helped build it.

There are some images of the railcars on the Florida State Park website.

Elisia Guerena FL Marathon Dec 10, 2020 Automobiles