William Monroe Trotter: Newspaper Man and Activist

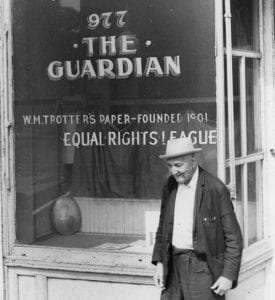

In the early 1900s, Boston’s City Hall Plaza was the city’s unofficial literary mecca. It housed bookstores, a library, and publishing companies, including that of William Monroe Trotter’s newspaper The Boston Guardian. In print from 1901 to the 1950s, this newspaper mirrored many of the same characteristics of its founder by demonstrating an unmatched intellectual focus, a stringent focus on racial justice issues, and an uncompromising stance in the battle for equality. Although Trotter’s newspaper was just one facet of his activism, it anchored many of his beliefs and bookmarked the story of his life as one of the United State’s most outspoken and radical Civil Rights activists.

William Monroe Trotter’s Formative Years

Trotter was born in Ohio as the son of a well-to-do African American family. His father was a Postal Service worker turned Democratic party employee who invested his considerable earnings ($40,000 in two years) in real estate. When his father died, Trotter carried on his strong intellect and passion for politics. As a resident of the affluent neighborhood of Hyde Park in Boston, Trotter graduated from high school as both valedictorian and class president. He went on to attend Harvard, where his drive for change found new outlets: he led the college’s abstinence club, was one of the campus’ first cyclists, and pushed for an anti-discrimination law after a Black athlete was denied a haircut in Cambridge. Trotter earned his Master’s Degree from Harvard in 1896. He spent the next few years striving to, and eventually succeeding, in securing employment at a real estate firm. In 1899, Trotter married his childhood friend Geraldine Pindell. Having already accomplished a considerable amount for an African American at that time, Trotter went on to establish the Boston Guardian: the second black-owned newspaper in the country that provided an outlet for underreported or untold stories of racial injustices and triumphs, as well as Trotter’s visionary—and sometimes vitriolic—ideas for Civil Rights.

The Boston Guardian: an Advocate for Racial Equality

The Guardian’s original headquarters were on Merchant’s Row in Boston’s present-day financial district. At the moment of the newspaper’s inception, the industry as a whole was just hitting its stride. Newspaper readership, in general, had doubled from 1880 to 1990, partially due to the contributions of journalist game-changers like Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. Muckraking journalism was at its heyday, with sensational headlines pulling in higher levels of readership while also challenging the status quo. This was the climate that Trotter launched his newspaper in: electric and fast-growing, with the standards of storytelling still in flux.

Trotter used his newspaper to report on African American stories that went unnoticed by the mainstream media (like the murder of an African American postmaster and his two-year-old daughter in South Carolina), share vital information with the community (like the passing of new Jim Crow laws or the status of sundown towns) as well as to share his viewpoints. Namely, Trotter espoused an uncompromising vision of racial justice that rejected the idea that change had to be gradual. Instead, Trotter advocated for absolute equality between African Americans and whites, coming down hard on those who opposed this view. This stance caused him to clash with many, including Civil Rights leader Booker T. Washington who argued that African Americans would settle for access to basic education and vocational training, instead of holding out for political equality and desegregation.

Trotter became famous for his clashes, which numbered many and with people as prolific as Woodrow Wilson. But he also had his allies, who helped him form the civil rights group the Niagara Movement as well as empower his plans to fight racial inequality. One story that exemplifies Trotter’s character well is when he donned a disguise and got a job as a cook on a ship crossing the Atlantic in order to deliver, in-person, papers on racial equality to the Versailles Peace Conference in Paris (Woodrow Wilson had denied him and his colleagues passports). Nevermind that the Conference heard about his concerns without his presence—Trotter was a determined force that demanded recognition.

The Boston Guardian faithfully covered Trotter’s exploits and gave voice to his views. Perhaps the second most famous incident that Trotter was involved in surrounded the 1915 silent film “The Birth of a Nation:” a highly racist film that covered U.S. history through the Reconstruction era and helped rebirth the Ku Klux Klan. Trotter protested the film’s release, which included a White House screening. He and his supporters even tried to buy tickets to the film’s Boston release but were denied access in a preemptive move to limit disruption to the film.

While Trotter’s adamant stance is admirable from an idealistic point of view, it was also his blindspot. His complete dismissal of anyone who did not wholeheartedly share in his rigid views alienated him from supporters. Espousing such a radical point of view caused The Boston Guardian to also flounder. By 1910, Trotter sold off much of his investment properties in order to support the newspaper. Then in 1918, his wife—an invaluable resource to the newspaper due to her bookkeeping skills—died after caring for black soldiers sick from the Spanish flu epidemic. Trotter’s finances, influence, and the popularity of his paper continued to wane until his 62 birthday, when he either fell from or jumped off his roof.

Trotter’s Legacy

Within his lifetime, many of Trotter’s pushes for equality were viewed as publicity stunts. People dismissed his antics and refused to take his rigid views seriously. One hundred years later, history casts a different perspective on Trotter: that his unrelenting stance provided a blueprint for future activists in the Civil Rights movement, and that his passion and drive—much of which was funneled into The Boston Guardian—gave African Americans a voice and perspective that was generations ahead of its time. For those interested in exploring his legacy on Route 1, check out Harvard University (especially the William Monroe Trotter Collaborative for Social Justice department which was formed in 2018), City Hall Plaza from where he ran his newspaper, The William Monroe Trotter Institute at the University of Massachusetts, and his home at 97 Sawyer Ave in Dorchester, which measures about five miles off the Route.

Elisia Guerena MA Boston Dec 10, 2020 Words