The Pine Tree State's Untold Story

Maine

When most people think of Maine, they conjure images of lighthouses perched on rocky cliffs, lobster shacks serving up fresh catches, and perhaps Stephen King lurking in the shadows of some Victorian mansion. While these snapshots aren’t wrong, they’re woefully incomplete. Maine is a paradox wrapped in fog and tied with a bow made of pine needles: simultaneously one of America’s oldest settled regions and one of its most remote frontiers.

I’ve spent the better part of two decades exploring this state, from the tourist-clogged streets of Bar Harbor to logging roads so remote they don’t appear on maps. What I’ve learned is that Maine resists easy categorization. It’s a place where 400-year-old fishing traditions coexist with cutting-edge environmental science, where million-dollar coastal estates sit just miles from towns that time forgot, and where the phrase “you can’t get there from here” isn’t a joke, it’s often truth.

This article isn’t going to tell you the ten best places to get lobster (though I’ll mention a few). Instead, it’s an attempt to understand Maine as Mainers understand it: a place shaped by granite and ice, stubbornness and ingenuity, isolation and fierce independence. It’s about the Maine that exists between the tourist seasons, beyond the gift shops, and off the beaten path.

Table of Contents

- History: Stubbornness as Survival Strategy

- Architecture: Building Against the Elements

- Culture: The Myth and Reality of Maine Character

- The Natural Environment: Living on the Edge

- Share your Maine route 1 memory

- Economic Realities: Making a Living at the End of the Road

- Political Landscape: Purple State Politics

- Looking Forward: Maine’s Uncertain Future

- Conclusion: The Persistence of Place

Maine’s geography reads like a trauma victim’s medical chart: scarred, battered, and reformed by millions of years of geological violence. The state sits on the edge of the North American plate, where ancient continents collided, mountains rose and fell, and glaciers carved the landscape like a drunk sculptor with a chainsaw.

The bedrock tells the story. In the western mountains, you’ll find metamorphic rocks that were once mud on an ancient ocean floor, compressed and cooked until they became the schists and gneisses that now form the backbone of the Appalachian chain. Along the coast, granite intrusions pushed up through the crust like slow-motion mushroom clouds, creating the pink and gray stone that would later build Boston and New York.

But it’s the ice that really made Maine what it is today. During the last glaciation, ice sheets up to a mile thick pressed down on the land, depressing it hundreds of feet. As the glaciers retreated – a process that only ended about 11,000 years ago – they left behind a landscape that looks like it was designed by a committee that couldn’t agree on anything.

The Coastal Paradox

Maine’s coastline is a geographic middle finger to logic. As the crow flies, it’s about 230 miles from Kittery to Eastport. But follow the actual shoreline (every inlet, peninsula, and island) and you’re looking at over 3,500 miles. That’s more than California, despite Maine having only a fraction of California’s straight-line coastal distance.

This fractured coast creates thousands of microclimates and micro-economies. In some places, you can stand on a peninsula and see two completely different weather systems on either side. The water temperature can vary by 10 degrees between spots just a few miles apart. This isn’t just trivia, it fundamentally shapes how people live, work, and think in coastal Maine.

The islands deserve special mention. Maine has somewhere between 3,000 and 4,600 islands, depending on your definition of “island” and the tide level when you’re counting. Only about 15 have year-round populations, and each of these is its own universe. Monhegan Island, 12 miles offshore, has no cars and generates its own power for only part of each day. Matinicus, even farther out, makes Monhegan look cosmopolitan. These aren’t quaint tourist destinations they’re the front lines of an ongoing experiment in whether 21st-century Americans can still live like their great-great-grandparents.

Related story

[article id=”14215″]

The Interior: America’s Last Frontier

Inland Maine might as well be another planet compared to the coast. The North Woods (that vast expanse of forest covering the northern two-thirds of the state) remains one of the largest undeveloped areas east of the Mississippi. This isn’t protected wilderness in the Western sense; most of it is private land, owned by timber companies and managed for logging.

The result is a landscape that’s simultaneously wild and industrial. You can drive for hours on private logging roads (if you know the gate codes), seeing nothing but trees, moose, and the occasional massive logging truck that will run you off the road without slowing down. There are mountains here that see fewer human footprints in a year than popular peaks in the White Mountains see in a day.

The geography of interior Maine enforces a certain lifestyle. Towns are few and far between. Paved roads are suggestions. Cell service is a rumor. In the unorganized territories (areas with no local government) you’re more likely to identify your location by township and range numbers than by any place name. It’s T4 R9, not “home.”

History: Stubbornness as Survival Strategy

Before the Beginning

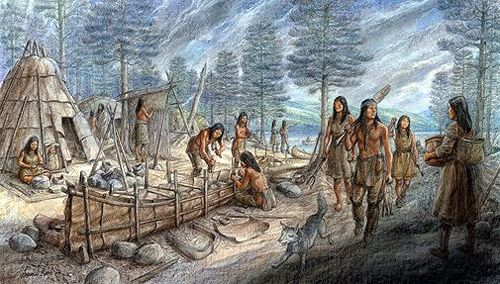

The human history of Maine starts at least 12,000 years ago, when Paleo-Indians followed the retreating glaciers north. These weren’t primitive people scratching out a living, they were sophisticated hunters with a complex understanding of the post-glacial environment. They knew where the caribou would be, when the salmon would run, and how to survive winters that would quickly overwhelm experienced modern outdoorsmen.

The Wabanaki peoples (the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Maliseet, and Micmac) developed from these early inhabitants. They created a civilization perfectly adapted to Maine’s challenging environment. Their seasonal rounds – coast in summer, interior in winter – made maximum use of available resources. Their social structures were flexible enough to handle the dispersed population density that Maine’s geography demanded.

One thing that’s often missed in historical accounts: the Wabanaki weren’t just hanging on until Europeans arrived. They had extensive trade networks reaching to the Great Lakes and beyond. They managed the forest through controlled burning. They had sophisticated governmental systems. When Europeans first arrived, they found not a wilderness, but a landscape that had been actively managed for thousands of years.

The European Mess

European exploration of Maine was basically a centuries-long bar fight where everyone kept forgetting what they were fighting about. The Vikings probably stopped by around 1000 AD. John Cabot possibly saw the coast in 1498. But the real chaos started in the 1600s.

The English tried to establish the Popham Colony in 1607, the same year as Jamestown. It lasted one Maine winter before the colonists said “screw this” and went home. The French claimed everything north of the Penobscot River. The English claimed everything period. The Wabanaki, quite reasonably, pointed out that they were already living there.

What followed was 150 years of the most confusing conflict in American history. The French and Indian Wars in Maine weren’t a war, they were a lifestyle. Settlements would be built, burned, abandoned, rebuilt, burned again. The same land might change hands a dozen times. Families would be split between French and English territory. Some people just gave up picking sides and decided to be whatever nationality wasn’t currently trying to kill them.

Statehood: The Great Real Estate Deal

Maine’s path to statehood in 1820 was less about manifest destiny and more about Massachusetts needing cash. Maine had been the “District of Maine” within Massachusetts since colonial times, but Massachusetts treated it like a distant, slightly embarrassing relative: useful for resources but not worth much attention.

The Missouri Compromise provided the excuse for separation. Missouri wanted to enter as a slave state, so they needed a free state for balance. Maine was available, Massachusetts needed money, and everyone pretended this made sense. On March 15, 1820, Maine became the 23rd state, finally free to be ignored on its own terms.

The early state period was rough. Maine had resources – timber, fish, granite, ice – but lacked the infrastructure to properly exploit them. The solution was typically Maine: do everything the hard way until it works. They built ships in towns barely connected to the outside world. They cut ice from ponds and shipped it to India. They quarried granite with hand tools and muscle.

The Industrial Revolution: Maine Style

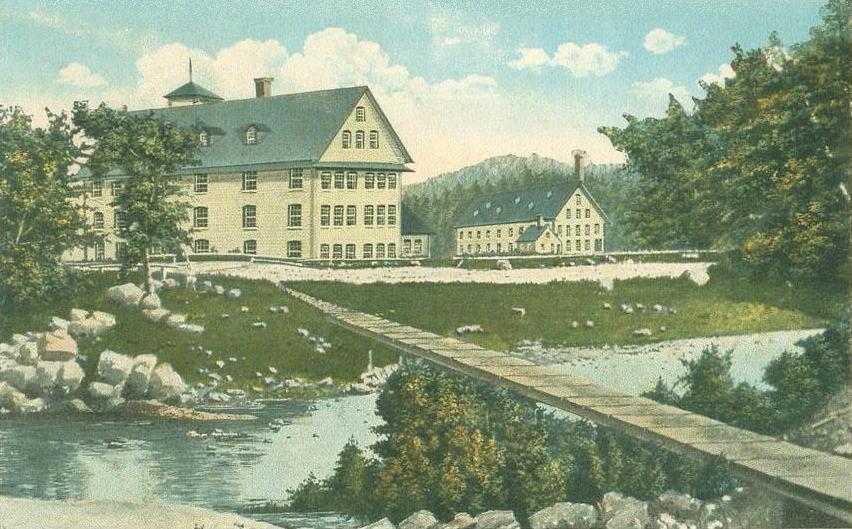

Maine’s industrial revolution was like everything else in Maine: idiosyncratic, stubborn, and surprisingly effective. While the rest of New England was building massive brick mills, Maine developed a distributed model of small mills on small rivers. Geography dictated this. Maine’s rivers drop quickly from the mountains to the sea, providing plenty of power but not the massive volume needed for Lowell-style operations.

The textile industry that developed was personal in scale. Mill owners knew their workers. Towns grew up around single mills. When the industry eventually collapsed, it took entire communities with it. You can still see the bones of this era in towns like Biddeford, Lewiston, and Sanford: massive brick buildings that once hummed with machinery, now converted to apartments, breweries, or simply left to decay.

The logging industry was Maine’s real economic engine. By the 1850s, Bangor was the lumber capital of the world. The Penobscot River was so thick with logs during the spring drives that you could allegedly walk across it. The wealth this generated built the mansions that still line West Broadway in Bangor, though the city’s glory days ended when the big trees were gone.

The 20th Century: Decline and Reinvention

The 20th century was not kind to Maine. The textile mills moved south. The virgin forests were gone. The granite quarries couldn’t compete with concrete. The shipbuilding industry contracted. Young people left for opportunities elsewhere. By the 1960s, Maine was the poorest state in New England, known mainly for lobsters, potatoes, and poverty.

But Maine has always been better at surviving than thriving. The state began reinventing itself, slowly and often painfully. Tourism, always present, became central to the economy. The environmental movement found fertile ground in a state where many people still lived close to the land. Artists and writers discovered they could afford to live in Maine, bringing new energy to old communities.

The paper industry, long a mainstay, began its slow decline in the 1980s. Mills that had employed thousands and anchored entire regions closed one by one. Towns like Millinocket and East Millinocket, built by and for Great Northern Paper, struggled to find new identities. Some succeeded; others are still searching.

Architecture: Building Against the Elements

The Indigenous Foundation

Before Europeans arrived, the Wabanaki peoples had already solved Maine’s fundamental architectural challenge: how to build comfortable, practical structures in a place where winter wants to kill you and summer brings both tourists and black flies.

Their solution was elegant: seasonal structures that could be assembled, disassembled, and moved as needed. Wigwams, dome-shaped structures covered with bark or hides, could be heated efficiently with a central fire. In summer, they built lighter structures near the coast. Nothing was permanent because permanence was a liability in a landscape that demanded flexibility.

This architectural philosophy – build what you need, when you need it, where you need it – would influence Maine building for centuries. Even today, the camp culture of Maine echoes these principles.

Colonial Confusion

Early European architecture in Maine was essentially a series of experiments in what wouldn’t kill you. The English brought their timber-framing traditions, but English buildings were designed for England’s mild, damp climate, not Maine’s arctic winters and humid summers.

The solution was typical Maine pragmatism: take what works, discard what doesn’t, and don’t worry about what it looks like. The Cape Cod house, despite its name, found its perfect expression in Maine. Low-slung to resist wind, with central chimneys for maximum heat retention, small windows to minimize heat loss, and steep roofs to shed snow, these houses were survival machines disguised as homes.

The Georgian and Federal styles that dominated the late 18th and early 19th centuries in prosperous coastal towns were essentially Cape Cod houses that had gotten rich. The basic form remained: center chimney, symmetrical facade but with fancy details added to show off wealth. Sea captains’ houses in towns like Kennebunkport and Wiscasset sprouted widows’ walks, fanlights, and elaborate doorways, but underneath, they were still fortresses against winter.

The Great Victorian Excess

The mid-19th century brought wealth and questionable taste to Maine architecture. The Gothic Revival, Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne styles exploded across the state like architectural fireworks. Bangor lumber barons built mansions that looked like wedding cakes. Portland shipping magnates created Gothic fantasies. Bar Harbor summer “cottages” redefined excess.

But even Victorian excess took on a Maine character. The wedding cake houses of Kennebunk (so called because of their elaborate carved wooden decoration) were simultaneously ostentatious and practical. The decoration was usually painted white, making the houses easier to see in snowstorms. The towers and turrets that look purely decorative actually provided ventilation in summer and could be closed off in winter to save heat.

The summer cottage architecture of Mount Desert Island deserves special mention. These “cottages”, which are mansions by any reasonable standard, represented a unique fusion of rustic and refined. Built of local granite and timber, with massive stone fireplaces and exposed wooden beams, they managed to be both palatial and (allegedly) simple. Most burned in the 1947 fire that devastated Bar Harbor, which was probably for the best. The few survivors offer a glimpse into an era when having 30 bedrooms was considered “roughing it.”

The Vernacular Tradition

But the real architectural story of Maine isn’t told in mansions and grand hotels. It’s told in the vernacular buildings that make up 99% of the built environment: fish houses, barns, camps, and ordinary homes built by ordinary people solving ordinary problems.

The connected farm buildings of Maine – “big house, little house, back house, barn” – represent one of America’s most distinctive regional building traditions. This isn’t picturesque nostalgia; it’s hardcore practicality. In winter, you could tend your animals without going outside. The configuration created a protected dooryard. Each section could be heated (or not) as needed. It’s architecture as survival strategy.

Fish houses and lobster shacks evolved their own aesthetic of pure function. Built on wharves over water, they needed to handle storms, tides, and the messy business of processing seafood. The result is a architecture of beautiful ugliness: buildings that make no concession to appearance but achieve a kind of grace through their perfect adaptation to purpose.

The Maine camp tradition deserves its own book. These aren’t camps in the usual sense, they’re seasonal homes, ranging from one-room shacks to elaborate compounds. But they share a philosophy: minimal intervention in the landscape, local materials, and an indoor-outdoor lifestyle. A proper Maine camp has a screened porch, a woodstove, and no insulation. It’s closed when the pipes would freeze and opened when the ice goes out. It represents a way of living that’s increasingly rare: seasonally, simply, and in direct contact with the environment.

Modern Maine: Between Preservation and Progress

Contemporary architecture in Maine faces a unique challenge: how to build for the future while respecting the past. The state has some of the strictest shoreland zoning laws in the country. Many towns have historic districts with stringent design requirements. The result is a built environment that changes slowly and carefully.

But there’s innovation happening, particularly in sustainable design. Maine architects have become leaders in cold-climate green building. The passive house movement has found fertile ground here. New buildings increasingly use local materials such as Maine timber, granite, and slate in contemporary ways.

The challenge is gentrification. As remote coastal properties become million-dollar estates, traditional forms get preserved but hollowed out of meaning. A fish house converted to a guest cottage might look authentic, but it represents the displacement of working waterfront by recreational uses. The architectural forms remain, but their connection to the landscape and economy that created them is severed.

Culture: The Myth and Reality of Maine Character

The Two Maines

The first thing to understand about Maine culture is that there isn’t one Maine culture; there are at least two, possibly more, existing in uneasy parallel.

There’s the Maine of the coast, particularly the southern coast which is increasingly wealthy, educated, and connected to the Boston-Washington corridor. This Maine hosts film festivals, farm-to-table restaurants, and million-dollar real estate. It votes Democratic, embraces environmental regulation, and sees Maine’s future in tourism, technology, and creative industries.

Then there’s the Maine of the interior and Downeast which tends to be rural, working-class, and increasingly left behind by the 21st-century economy. This Maine drives trucks, cuts wood, eats beaver and moose, and struggles to pay for heating oil. It votes Republican (or for independents), resents environmental regulations that seem to prioritize tourists over residents, and sees its way of life disappearing.

These two Maines eye each other with suspicion across a cultural divide that’s geographic, economic, and philosophical. The tension between them shapes everything from state politics to local zoning battles.

The Myth of the Mainer

The stereotypical Mainer is taciturn, independent, suspicious of outsiders and new ideas but has enough truth to persist but enough falsehood to be dangerous. Yes, Maine culture values self-reliance. Yes, there’s a skepticism of authority that runs deep. But the image of the flinty Yankee lobsterman obscures the complexity of contemporary Maine culture.

The reality is that Maine has always been more diverse than its reputation suggests. French-Canadian culture dominates in the St. John Valley and mill towns like Lewiston. The Wabanaki nations maintain vibrant communities despite centuries of attempted erasure. Portland has significant Somali, Sudanese, and other African immigrant populations. Each group has added layers to Maine culture while adapting to Maine conditions.

The famous Maine accent (“ayuh” and “wicked” and dropped r’s) is actually multiple accents. The coastal accent differs from the County accent which differs from the French-influenced accents of the Valley. And increasingly, you’re as likely to hear standard American English as any regional dialect.

Work and Identity

In Maine, more than most places, what you do defines who you are. This isn’t about career ambition, it’s about the integration of work and life that comes from living in a place where many jobs are seasonal, weather-dependent, and tied to specific places.

Lobstering isn’t just a job; it’s an identity that encompasses family history, community standing, and ecological knowledge. The territories where lobstermen set their traps are inherited and defended. The knowledge of where to set traps when is passed down through generations. The social structure of the harbor gang provides both support and enforcement of unwritten rules.

The same is true for other traditional occupations. Loggers don’t just cut trees, they read the forest, understand weather patterns, and maintain equipment in conditions that would defeat most machines. Blueberry rakers follow the same fields their grandparents worked. Clam diggers know their flats like suburban commuters know their routes to work.

But these traditional occupations are under pressure. Climate change is pushing lobster populations north. Mechanization has eliminated many woods jobs. Aquaculture is changing the working waterfront. Young people face a choice: adapt to the new economy or leave for opportunities elsewhere.

The Creative Migration

Starting in the 1960s but accelerating recently, Maine has attracted artists, writers, and other creative types seeking affordable living and inspirational landscapes. This migration has transformed some communities while barely touching others.

The Wyeth family made Maine landscapes iconic. Stephen King made Maine horror archetypal. But beyond the famous names, thousands of lesser-known artists have found in Maine a place where they can afford to live while making art.

This creative migration has been a mixed blessing. In places like Portland, Rockland, and Belfast, artists have revitalized downtowns and created vibrant cultural scenes. Galleries, studios, and performance spaces have filled empty storefronts. But they’ve also driven up real estate prices and changed community character in ways that not everyone appreciates.

The tension between economic development and cultural preservation plays out in countless small conflicts. When does revitalization become gentrification? How many galleries can a fishing village support before it stops being a fishing village? These aren’t abstract questions in Maine, they’re daily negotiations in communities struggling to survive while maintaining their identity.

Food: Beyond the Lobster Roll

Maine food culture embodies all the contradictions of Maine itself. There’s the marketed Maine – lobster rolls, blueberry pie, whoopie pies – that appears on postcards and food shows. Then there’s the Maine that Mainers eat: pot roast, baked beans, and whatever’s on sale at Hannaford.

The local food movement has found passionate advocates in Maine, but it builds on existing traditions rather than replacing them. Mainers have always grown gardens, preserved food, and hunted deer. The new emphasis on local sourcing connects to old patterns of self-sufficiency.

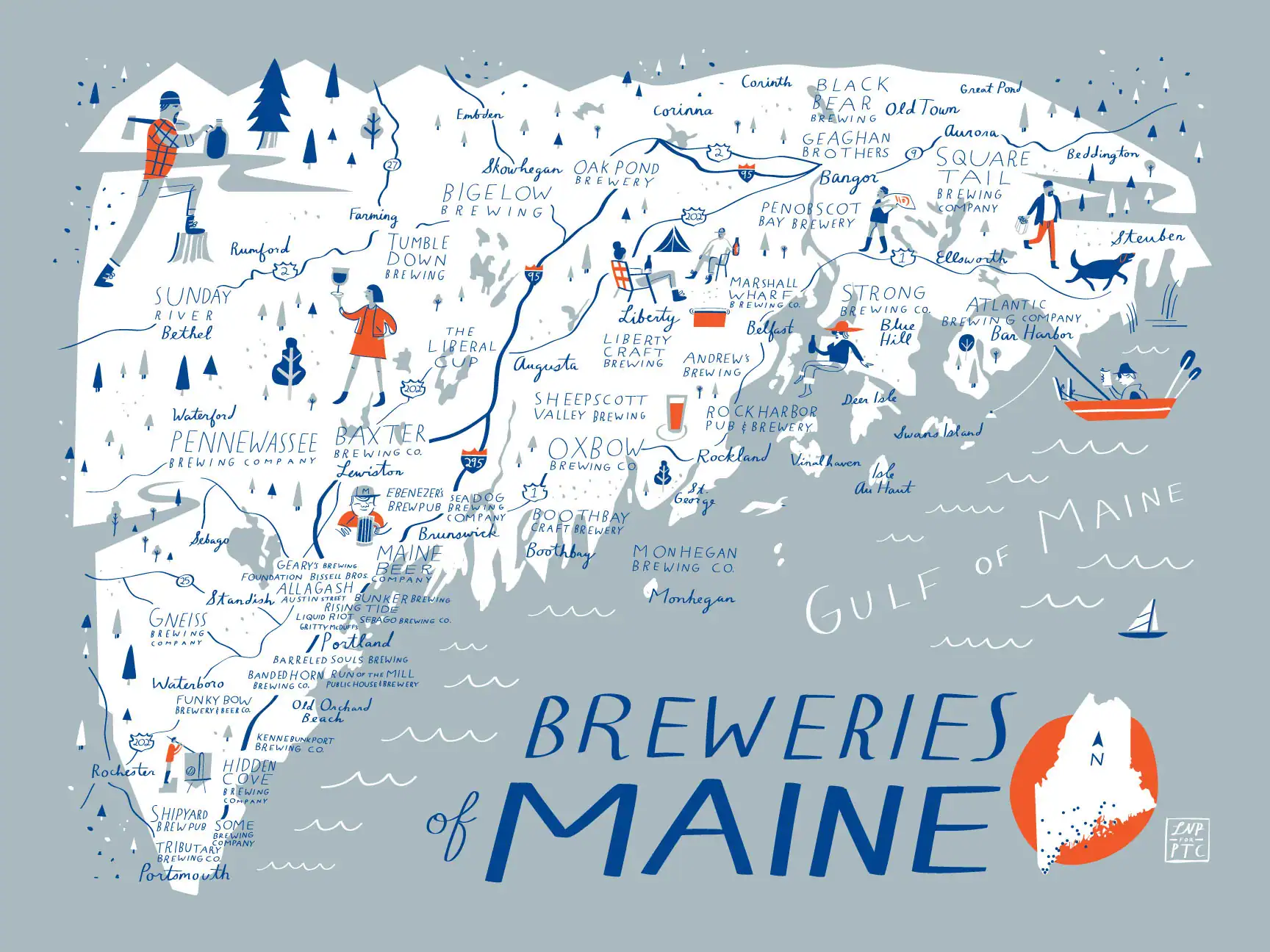

The explosion of craft breweries, distilleries, and restaurants has created a new food culture that coexists uneasily with the old. You can get a $200 tasting menu in Portland or a $5 plate of beans and hot dogs at a public supper. Both are authentically Maine, serving different populations with different resources.

The Season Cycle

Maine culture is fundamentally seasonal in ways that climate-controlled America has largely forgotten. The rhythm of the year shapes everything from work to social life to mental health.

Summer is performance season when the population doubles with tourists, seasonal residents, and summer workers. Coastal towns put on their best face, restaurants extend their hours, and everyone tries to make enough money to survive winter. It’s exhausting, profitable, and slightly false.

Fall is recovery season, when locals reclaim their towns, tourists go home, and the landscape explodes in color. It’s the favorite season of many Mainers, offering perfect weather and a sense of ownership. The fall fairs celebrate agricultural traditions that remain central to rural Maine identity.

Winter is endurance season. The tourist economy shuts down, heating bills soar, and communities turn inward. This is when Maine’s social capital (the networks of mutual support that keep communities functioning) becomes visible. People check on elderly neighbors, share firewood, and gather in the few businesses that stay open.

Spring is practically a myth: a muddy, buggy transition that Mainers call “mud season” for good reason. Roads that were fine when frozen become impassable. The black flies emerge with a vengeance. Everyone gets a little crazy waiting for real warmth.

The Natural Environment: Living on the Edge

The Forest Primeval (Sort Of)

Maine markets itself as a wilderness, but the reality is more complex. The forests that cover 90% of the state – the highest percentage of any state – are not primeval wilderness but working forests that have been cut, burned, and regrown multiple times.

The original forests (massive white pines, spruce, and hemlock) were largely gone by 1900. What grew back was different: smaller trees, different species mix, adapted to different conditions. The forest of today would be unrecognizable to a Wabanaki hunter of 500 years ago.

But this second-growth forest has its own majesty. The Northern Forest that great sweep of spruce-fir that extends from Maine through the Adirondacks to Minnesota remains one of the largest intact forest ecosystems in the United States. It supports moose, black bear, lynx, and possibly wolves (depending on who you believe and how much they’ve had to drink).

The forest is also working land. Despite environmental protests, most of Maine’s forest is privately owned and actively logged. This isn’t the clear-cutting of the Pacific Northwest: Maine loggers learned that lesson the hard way. Modern forestry in Maine aims for sustainability, though definitions of “sustainable” vary depending on who’s defining it.

The Ocean: Provider and Threat

Maine’s relationship with the Atlantic is like a long marriage: intimate, complicated, and impossible to leave. The Gulf of Maine is one of the most productive marine ecosystems in the world, supporting fisheries that have sustained communities for 400 years.

But the Gulf is changing faster than at any time in recorded history. Water temperatures are rising rapidly: faster than almost anywhere else in the global ocean. This is pushing traditional species north and bringing southern species into Maine waters. Lobster, currently thriving in Maine waters as they warm, may eventually follow the pattern of cod and move to Canada.

The working waterfront – those precious strips of land where fishing boats can tie up and unload – is under constant pressure from development. Every wharf converted to condos is a piece of infrastructure that can’t be replaced. The state has programs to protect working waterfront, but money and political will are limited.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. Sea level rise threatens coastal communities. Storm surges reach farther inland. The 100-year storms seem to come every decade now. Communities that have existed for centuries are calculating how many more decades they have left.

Wildlife: The Returnees and the Departed

Maine’s wildlife tells a story of destruction and partial redemption. Many species that were extirpated in the 19th and early 20th centuries have returned, while others remain missing.

Moose, nearly extinct in Maine by 1900, now number around 75,000. They’ve become a tourism icon and a highway hazard. But climate change threatens them in new ways: warmer winters allow tick populations to explode, and some moose are literally being bled to death by tens of thousands of ticks.

Wild turkeys, absent for a century, were successfully reintroduced and now seem to be everywhere. Eagles, once reduced to a handful of pairs, have recovered dramatically. Peregrine falcons nest on mountain cliffs and urban buildings.

But the wolf remains absent, despite occasional sightings that spark fierce debate. The woodland caribou, once abundant, are gone. The Atlantic salmon, despite millions spent on restoration, remain at critically low levels. Each absence represents a broken link in the ecological chain.

The debate over predators encapsulates Maine’s environmental tensions. Should wolves be reintroduced? Should hunting laws be relaxed to control growing deer populations? How do you balance ecological integrity with human safety and economic interests? There are no easy answers, only competing values and imperfect compromises.

Share your Maine route 1 memory

Do you have a story you would like to share? We want to hear it!

Create a View to tell a unique story about a specific place

Want to see what others wrote about Maine?

Our Travel map has over 1400 posts from users like you

We have 2 types of content at Route1views:

- View: A unique experience at a single location

- Trip: A collection of experiences at different places, connected through a ‘road trip’

- Most first-time posters choose to make a View

A note about Route 1 Views

We are a user-driven social media site for celebrating and sharing stories along historic Route 1 USA. Using our platform is FREE forever and we don’t play any tricks. We don’t share your data or spam you with emails. We are all about sharing!

Economic Realities: Making a Living at the End of the Road

The Traditional Economy Under Pressure

Maine’s traditional resource-based economy faces challenges from every direction. Lobstering, the most visible and valuable fishery, exists in a state of nervous prosperity. Catches remain high, prices are good, but everyone knows it can’t last forever. Young people face barriers to entry, a boat and gear can cost $500,000 or more. Climate change looms. The bait fish that lobstermen depend on are getting harder to find.

Forestry, once the backbone of the Maine economy, employs a fraction of the people it once did. Mechanization means one operator with a feller-buncher does the work of a dozen foresters with chainsaws. The paper mills that once provided good-paying jobs have mostly closed. What remains is increasingly specialized: high-end saw logs, biomass for energy, specialty products.

Agriculture hangs on through stubbornness and adaptation. The dairy industry that once dominated has shrunk to a handful of farms. But new crops and approaches have emerged. Maine grows excellent potatoes, blueberries, and increasingly, diverse vegetables for local markets. The organic farming movement found early adopters in Maine, and the state has more farmers’ markets per capita than almost anywhere.

The Tourist Industrial Complex

Tourism has become Maine’s default economic development strategy, but it’s a devil’s bargain. Yes, tourism brings money: about $6 billion annually. But tourist jobs are often seasonal and low-wage. The infrastructure tourists require (hotels, restaurants, gift shops) can overwhelm small communities. And tourist dollars flow unevenly, concentrating in a few hotspots while bypassing communities that might need them most.

The COVID-19 pandemic complicated the tourist relationship further. In 2020, many Mainers were simultaneously desperate for tourist dollars and terrified of tourist diseases. The influx of remote workers (people who discovered they could work from anywhere and chose Maine) drove up real estate prices and strained small-town resources.

Short-term rentals like Airbnb have transformed and distorted local housing markets. In some coastal towns, there are more short-term rentals than year-round housing units. Workers can’t find places to live in the communities where they work. The social fabric tears when neighborhoods become ghost towns nine months of the year.

The New Economy: Promises and Limitations

Maine has tried to build a new economy based on technology, creative industries, and remote work. There have been successes: Portland has a thriving tech scene, craft brewing has become a significant industry, and some former mill towns have reinvented themselves as arts centers.

But the new economy has limitations in a rural state. Broadband access remains spotty and you can lose cell service 20 minutes from Portland. The educational infrastructure needed to support tech industries is concentrated in a few places. Young people with skills and ambition still often leave for opportunities elsewhere.

The remote work revolution offers promise but also peril. Yes, people with Boston salaries can now live in coastal southern Maine, bringing spending power to small communities. But they also drive up housing costs and can change community character in ways that create resentment. The COVID-era influx of remote workers exacerbated existing tensions between newcomers and natives.

Energy: The Hidden Economic Driver

Energy costs shape Maine’s economy in ways outsiders don’t always understand. Maine has the oldest housing stock in the nation, much of it poorly insulated. Heating oil dependency means that many families spend $3,000-$5,000 or more each winter on heat. When oil prices spike, it’s an economic crisis.

The state has pushed hard for renewable energy, with mixed results. Wind power projects have created jobs but also fierce opposition in communities that don’t want ridgelines covered in turbines. Solar is growing rapidly but faces challenges in a northern state with long winters. Hydropower from Quebec provides clean electricity but makes Maine dependent on foreign sources.

The energy transition creates winners and losers. Heat pump installers can’t keep up with demand. Solar panel installers are booming. But the guys who deliver heating oil – often small, family businesses – see their future disappearing. It’s creative destruction in real time, with real consequences for real communities.

Political Landscape: Purple State Politics

The Independent Streak

Maine politics defies easy categorization. It’s a blue state that elected Paul LePage, a Tea Party Republican, as governor twice. It’s a state where Bernie Sanders crushed in the Democratic primary but where Susan Collins (a moderate Republican) keeps winning despite national Democratic money flooding in to defeat her.

The key to understanding Maine politics is understanding that Mainers hate being told what to do, especially by people in other States. This libertarian streak crosses party lines. Democrats in Maine tend to be more skeptical of gun control than national Democrats. Republicans in Maine tend to be more accepting of environmental regulation than national Republicans. Everyone agrees that Massachusetts drivers are terrible.

Local politics matters more in Maine than in many states. Town meeting government remains common, where citizens directly vote on budgets and ordinances. Select boards and planning boards wield enormous power over development. These local battles (over a new Dollar General, a proposed cell tower, or short-term rental regulations) shape daily life more than anything happening in Augusta or Washington.

The Rural-Urban Divide

Maine’s political geography mirrors its cultural geography. The Portland area and southern coast lean strongly Democratic. The rural interior and Downeast lean Republican. But it’s not a simple red-blue divide, it’s more about worldview than party affiliation.

The divide plays out in debates over everything from gun control to environmental regulation to education funding. Rural Mainers feel ignored and condescended to by the Portland-centric political establishment. Urban and suburban Mainers feel held back by rural resistance to change. Both sides have legitimate grievances.

The North Woods national monument debate exemplified these tensions. When President Obama designated Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument in 2016, it was either a visionary act of conservation or federal overreach, depending on who you asked. The debate wasn’t really about the land – it was about who gets to decide Maine’s future.

Environmental Politics: Conservation vs. Jobs

Environmental issues in Maine can’t be separated from economic issues. When environmental regulations shut down a mill or restrict logging, it’s not an abstract policy debate, it’s hundreds of families losing their livelihoods. When development threatens a fishing ground or scenic view, it’s not just about aesthetics, it’s about the resources that sustain communities.

The state has tried to balance these interests with mixed success. The Land Use Planning Commission regulates development in the unorganized territories. The Department of Environmental Protection enforces some of the strictest environmental laws in the nation. But enforcement depends on political will and funding, both of which fluctuate.

Climate change adds urgency to these debates. Maine is already seeing effects: warmer winters, shifting species, stronger storms. The state has ambitious climate goals, but meeting them requires changes that threaten traditional industries. How do you transition a petroleum-dependent state to renewable energy without leaving people behind? Nobody has good answers.

Looking Forward: Maine’s Uncertain Future

The Demographic Challenge

Maine faces a demographic crisis that threatens its future more than any environmental or economic challenge. It’s the oldest state in the nation by median age. Young people continue to leave for opportunities elsewhere. The birth rate is below replacement level. Without immigration, Maine’s population would be shrinking.

This creates cascading problems. School districts consolidate or close as enrollment drops. The workforce shrinks just as baby boomers need more services. Tax bases erode in rural communities. The social institutions that bind communities—churches, granges, volunteer fire departments—struggle to find new members.

Immigration offers one solution, but it’s politically fraught. The Somali community in Lewiston has revitalized a dying mill city, but not without tension. Immigrant farm workers sustain the agricultural economy, but face exploitation and uncertain legal status. Maine needs new residents, but struggles with becoming more diverse.

Climate Adaptation

Maine will be profoundly shaped by climate change, both directly and indirectly. As the American South becomes unbearably hot and the West runs out of water, Maine’s abundant water and (relatively) cool temperatures may attract climate migrants. That would represent a reverse trend from the 1970’s and 80’s, when “Rust Belt” populationsmoved to the “Sun Belt”. Climate migration could revitalize the state or overwhelm its infrastructure and culture.

The lobster industry illustrates the complexity. Warming waters have been good for Maine lobster in the short term, as the population has shifted north from Southern New England. But continued warming will eventually push lobster into Canadian waters. The industry that defines coastal Maine may have only decades left.

Communities are starting to adapt. Some towns are retreating from the waterfront, moving infrastructure inland. Others are hardening defenses, building seawalls and elevating buildings. The costs are enormous for communities with small tax bases. Federal help is limited and comes with strings attached.

The Identity Question

The fundamental question facing Maine is what kind of place it wants to be. Can it maintain its rural, resource-based character in a globalized, urbanized world? Should it try? Or should it embrace change and risk losing what makes it distinctive?

Wait and see. The tourist economy that many depend on requires maintaining the “authentic” Maine that tourists come to see. But maintaining authenticity as a performance eventually hollows out actual authenticity. The new economy of remote work and creative industries brings needed dynamism but also displacement and cultural change.

Different communities are choosing different paths. Portland has embraced growth and change, becoming a small but vibrant city. Towns like Eastport and Lubec are betting on arts and culture to revive their economies. Others are doubling down on traditional industries, hoping to ride out the changes. Some are simply trying to manage decline with dignity.

Conclusion: The Persistence of Place

After all these words, I’m not sure I’ve explained Maine any better than when I started. It remains a place that resists easy summary or glib conclusions. It’s poor but proud, beautiful but harsh, traditional but adaptable. It’s a place where you can still disappear if you want to, but also increasingly a place where you can’t afford to live.

What strikes me most about Maine is its sheer persistence. This is a place that shouldn’t work, it’s too far north, too rocky, too remote. The economy is always struggling. The weather is terrible half the year. Young people leave and don’t come back. By any rational calculation, Maine should be emptying out, returning to forest.

But it persists. Communities that should have died when the mill closed find new purpose. Fisheries that should have collapsed adapt and survive. People who could live easier lives elsewhere choose to stay, held by ties of family, tradition, or sheer stubbornness.

This persistence isn’t romantic, rather it’s often grinding and thankless. It’s held together by informal networks of mutual aid that social scientists would call “social capital” but Mainers just call “helping out.” It’s sustained by a sense of place that runs deeper than economic calculation.

Maine’s future is uncertain. Climate change, demographic decline, economic transformation: the challenges are real and serious. But Maine has survived 400 years of European settlement, multiple economic collapses, and countless predictions of doom. It’s still here, still somehow itself despite all the changes.

The Maine that emerges from the current transformations won’t be the Maine of postcards and tourist brochures. It will be more diverse, more connected to the wider world, probably more urban. But I suspect it will still be recognizably Maine: shaped by granite and ice, defined by water and woods, sustained by the stubborn refusal to be anywhere else.

That’s the Maine I’ve come to know. Not the simple paradise of summer visitors or the backward wilderness of urban stereotypes, but a complex place full of contradictions and surprises. It’s a place that rewards patience, punishes assumption, and demands respect. It’s not for everyone. But for those who get it, who understand the trade-offs and accept the challenges, there’s nowhere else quite like it.

The fog is rolling in as I finish writing this, obscuring the islands and muffling the sounds of the harbor. Soon, the foghorn will start its mournful call. It’s a sound that hasn’t changed in a century, marking the entrance to safe harbor for boats feeling their way through the murk. It’s a good metaphor for Maine itself: a steady signal in the fog, guiding those who know how to listen safely home.